Misinformation vs. Disinformation: How to Tell the Difference

Updated: Dec. 18, 2023

Even the savviest of us can be fooled. Here's how to recognize fake info.

The Reader’s Digest Version:

|

If you’ve been having a hard time separating factual information from fake news, you’re not alone. Nearly eight in ten adults believe or are unsure about at least one false claim related to COVID-19, according to a report the Kaiser Family Foundation published late last year. Other areas where false information easily takes root include climate change, politics, and other health news. That’s why it’s crucial for you to able to identify misinformation vs. disinformation.

Those are the two forms false information can take, according to University of Washington professor Jevin West, who cofounded and directs the school’s Center for an Informed Public. As part of the University of Colorado’s 2022 Conference on World Affairs (CWA), he gave a seminar on the topic, noting that if we hope to combat misinformation and disinformation, we have to “treat those as two different beasts.”

The difference between disinformation and misinformation is clearly imperative for researchers, journalists, policy consultants, and others who study or produce information for mass consumption. For the general public, “it’s more important not to share harmful information, period,” says Nancy Watzman, strategic advisor at First Draft, a nonpartisan, nonprofit coalition that works to protect communities from false information. But to avoid it, you need to know what it is.

Keep reading to learn about misinformation vs. disinformation and how to identify them. Then arm yourself against digital attacks aimed at harming you or stealing your identity by learning how to improve your online security and avoid online scams, phone scams, and Amazon email scams.

What is misinformation?

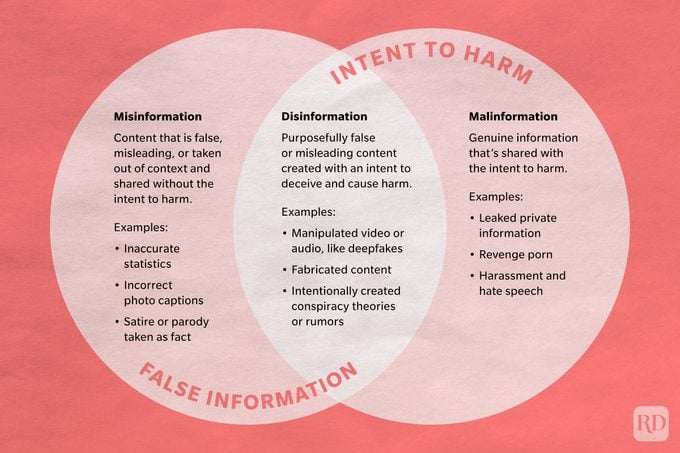

Misinformation contains content that is false, misleading, or taken out of context but without any intent to deceive.

When family members share bogus health claims or political conspiracy theories on Facebook, they’re not trying to trick you—they’re under the impression that they’re passing along legit information. In reality, they’re spreading misinformation.

Examples of misinformation

Misinformation ran rampant at the height of the coronavirus pandemic. Consider claims of false COVID-19 treatments that spread across social media like, well, the virus they claimed to cure. Those who shared inaccurate information and misleading statistics weren’t doing it to harm people. In fact, most were convinced they were helping.

This type of false information can also include satire or humor erroneously shared as truth. “Misinformation can be your Uncle Bob [saying], ‘I’m passing this along because I saw this,'” Watzman notes.

Misinformation is unnervingly widespread online—it’s enough to make you want to disappear from the Internet—and it doesn’t just cause unnecessary confusion. It can lead to real harm.

“People die because of misinformation,” says Watzman. “It could be argued that people have died because of misinformation during the pandemic—for example, by taking a drug that’s not effective or [is] even harmful.” If misinformation led people to skip the vaccine when it became available, that, too, may have led to unnecessary deaths.

Misinformation can be harmful in other, more subtle ways as well. It prevents people from making truly informed decisions, and it may even steer people toward decisions that conflict with their own best interests. Once a person adopts a misinformed viewpoint, it’s very difficult to get them to change their position.

What is disinformation?

Disinformation is false or misleading content purposefully created with an intent to deceive and cause harm. It’s typically motivated by three factors: political power or influence, profit, or the desire to sow chaos and confusion.

This type of fake information is often polarizing, inciting anger and other strong emotions. It can lead people to espouse extreme views—even conspiracy theories—without room for compromise. This, in turn, generates mistrust in the media and other institutions. And when trust goes away from established resources, West says, it shifts to places on the Internet that are not as reliable.

“Democracy thrives when people are informed. If they’re misinformed, it can lead to problems,” says Watzman. In some cases, those problems can include violence.

Examples of disinformation

While many Americans first became aware of this problem during the 2016 presidential election, when Russia launched a massive disinformation campaign to influence the outcome, the phenomenon has been around for centuries.

In fact, Eliot Peper, another panelist at the CWA conference, noted that in 10th-century Spain, feudal lords commissioned poetry—”the Twitter of the time”—with verses that both celebrated their reign and “threw shade on their neighbors.” The lords paid messengers to spread the compositions far and wide, in a “shadow war of poems.” Some of the poems told blatant lies, such as accusing another lord of being an adulterer—or worse. “Even by modern standards, a lot of these poems were really outrageous, and some led to outright war,” he said.

And, well, history has a tendency to repeat itself. In modern times, disinformation is as much a weapon of war as bombs are. In the Ukraine-Russia war, disinformation is particularly widespread. In an attempt to cast doubt on Ukrainian losses, for instance, Russia circulated a video claiming Ukrainian casualties were fake news—just a bunch of mannequins dressed up as corpses. Of course, the video originated on a Russian TV set.

As the war rages on, new and frightening techniques are being developed, such as the rise of fake fact-checkers. In Russia, “fact-checkers” were reporting and debunking videos supposedly going viral in Ukraine. The catch? The videos never circulated in Ukraine. The fact-checking itself was just another disinformation campaign.

“We could check. We could see, no, they weren’t [going viral in Ukraine],” West said. “They were actually fabricating stories to be fact-checked just to sow distrust about what anyone was seeing.”

Beyond war and politics, disinformation can look like phone scams, phishing emails (such as Apple ID scams), and text scams—anything aimed at consumers with the intent to harm, says Watzman. “You’re deliberately misleading someone for a particular reason,” she says.

The difference between disinformation and misinformation

In general, the primary difference between disinformation and misinformation is intent. Both are forms of fake info, but disinformation is created and shared with the goal of causing harm.

Usually, misinformation falls under the classification of free speech. But disinformation often contains slander or hate speech against certain groups of people, which is not protected under the First Amendment.

Another difference between misinformation and disinformation is how widespread the information is. Misinformation tends to be more isolated. “Disinformation has multiple stakeholders involved; it’s coordinated, and it’s hard to track,” West said in his seminar, citing as an example the “Plandemic” video that was full of conspiracy theories and spread rapidly online at the height of the coronavirus pandemic. “It was taken down, but that was a coordinated action.”

One thing the two do share, however, is the tendency to spread fast and far. The rise of encrypted messaging apps, like WhatsApp, makes it difficult to track the spread of misinformation and disinformation. And, of course, the Internet allows people to share things quickly. “The virality is truly shocking,” Watzman adds. The viral nature of the internet paired with growing misinformation is one of the reasons why more and more people are choosing to stay away from media platforms. Here are some of the good news stories from recent times that you may have missed.

What is a deepfake?

Spend time on TikTok, and you’re bound to run into videos of Tom Cruise. He’s dancing. He’s doing a coin trick. He’s not really Tom Cruise.

Deepfake videos use deep learning, a type of artificial intelligence, to create images that place the likeness of a person in a video or audio file. They may look real (as those videos of Tom Cruise do), but they’re completely fake.

And there’s cause for concern. Deepfakes have been used to cast celebrities in pornography without their knowledge and put words into politicians’ mouths. Experts believe that as the technology improves, deepfakes will be more than just a worry of the rich and famous; revenge porn, bullying, and scams will spread to the masses.

But what really has governments worried is the risk deepfakes pose to democracy. There’s been a lot of disinformation related to the Ukraine-Russia war, but none has been quite as chilling as the deepfake video of Ukrainian president Volodymyr Zelensky urging his people to lay down their weapons. It was quickly debunked, but as the tech evolves, it could make such disinformation tougher to spot. And it could change the course of wars and elections.

What is malinformation?

Like disinformation, malinformation is content shared with the intent to harm. The big difference? Malinformation involves facts, not falsities. Leaked emails and personal data revealed through doxxing are examples of malinformation. Harassment, hate speech, and revenge porn also fall into this category.

How to recognize misinformation and disinformation

So, you understand what’s misinformation vs. disinformation, but can you spot these phonies in your everyday life? There are a few things to keep in mind.

For starters, misinformation often contains a kernel of truth, says Watzman. And it also often contains highly emotional content. “If something is making you feel anger, sadness, excitement, or any big emotion, stop and wait before you share,” she advises. “The stuff that really gets us emotional is much more likely to contain misinformation.”

She also recommends employing a healthy dose of skepticism anytime you see an image. “Images can be doctored,” she says. “We see it in almost every military conflict, where people recycle images from old conflicts.” To determine if an image is misleading, you might try a reverse image search on Google to see where else it has appeared.

Both Watzman and West recommend adhering to the old adage “consider the source.” Before sharing something, make sure the source is reliable. In fact, it’s a good idea to see if multiple sources are reporting the information; if not, your original source may not be trustworthy. When in doubt, don’t share it.

If you do share something—even if it’s just to show others how blatantly false something is—it’s better to take a screenshot than to hit “share,” which only encourages the algorithms to continue to spread it.

West says people should also be skeptical of quantitative data. (Think: the number of people who have died from COVID-19.) “It’s really effective in spreading misinformation. You can BS pretty well when you have a fancy graphic or a statistic or something that seems convincing,” West said at the CWA conference, noting that false data has been used by research institutions and governments to build policies, all because we haven’t taught people how to question quantitative information.

In the end, he says, “extraordinary claims require extraordinary evidence.”

Keep protecting yourself by learning the signs an Instagram ad can’t be trusted, how to avoid four-word phone scams, and other ways to ensure your digital security.

Sources:

- Jevin West, associate professor at the University of Washington and cofounder and director of the UW Center for an Informed Public

- Nancy Watzman, strategic advisor for First Draft

- Eliot Peper, writer and tech consultant

- Conference on World Affairs: “Calling Bull—: Telling Truth from Fiction in the Information Age”