Meet the Man Recycling Hotel Soap Bars for a Cleaner, Greener World

Updated: Oct. 05, 2022

Used soap bound for the trash gets a second life through recycling—and saves resources and lives in the process

Fourteen years ago, Shawn Seipler had an aha moment about soap. See, the hospitality industry generates an estimated 440 billion pounds of solid waste every year, much of it from soap and bottled amenities. That’s almost 60 pounds of waste for every living human per year.

Seipler, who at the time was a top-level executive running a global sales team for a technology company, figured he could do some good while scratching a lifelong itch: to start his own company. His entrepreneurial spirit goes back to his childhood, when he sold lemonade, washed cars and windows, mowed lawns and babysat to make a few bucks. The combination of childhood entrepreneurship and two decades of experience in sales and technology propelled him to act.

Sandwiched between long workdays and frequent travel was Seipler’s endless research on sustainable living, recycling and other environmental topics from an entrepreneurial perspective. You can recycle pretty much anything, he soon found out—soap included.

Cue his lightbulb moment about the future of recycling hotel toiletries: Someone needed to do something about all that wasted soap. And Seipler was that someone.

Researching a solution to a global problem

Seipler’s luggage was jam-packed, which was how he ended up in a Minneapolis hotel room contemplating hotel soap.

It was 2008, and he was on a business trip. That night, he found himself considering the single-use toiletries found in hotel rooms. He never kept the bar of soap or ball of shampoo hotels provided to every guest. In his case, he didn’t have room in his luggage.

But Seipler wondered what happened to all that partially used soap and shampoo. Out of sheer curiosity, he called the front desk and learned that it was all thrown away.

He did some back-of-the-envelope math and conservatively estimated that, in the United States alone, hotels discarded at least a million bars of semi-used soap every day. After returning from the business trip, he dedicated himself to researching a process called re-batching, which involves melting soap down and then reforming it to be reused—less upcycling and more recycling of old materials.

Seipler soon became obsessed with the idea of doing something with all that wasted soap.

He took advantage of business trips with other sales executives to do some firsthand product research rather than relying on Google. “I would make [sales executives] bring me their used and dirty soap from their hotel room when we were leaving for our business trips,” he says. “If I saw open rooms and there was a room attendant cleaning, [my sales executives and I] would have to dart in and grab the soap and come out.”

With bars of half-used soap smuggled in his suitcase, Seipler ended his business trips with souvenirs of other people’s showers. Some might’ve considered it gross work, but Seipler saw it as the first step in turning other people’s trash into something truly useful.

Doing the dirty work

Seipler returned from business trips loaded with soap he and his sales executives had collected. Usually, his haul included a bag of used soap and often boxes of new soap.

Then he got to work. Using a potato peeler, he removed the dirty surface of the used soap. He then cut the cleaned soap with a knife and put it into a food processor, which gave the soap a powder-like form. Seipler mixed in some water, then he put his concoction in the oven, experimenting with variables like oven temperature and cooking time, in true entrepreneurial fashion.

Once the soap mixture cooled and hardened, he observed how the soap came out and recorded his observations in a notebook. He also tested his handiwork in the shower and while washing his hands. To this day, he still has the notebook he used to iterate recipes until he had a soap product he could work with at scale.

Hand-washing for health

By early 2009, after months of trial and error that Seipler enjoyed, he had worked out the perfect recipe for turning old soap into new bars. But he still didn’t have a clear idea of what he would do with it.

Then he came across several studies showing that the simple act of giving children hand soap could halve the number of deaths from pneumonia and diarrheal disease, at the time the world’s two leading causes of death among children.

“That was the aha moment,” he says. “That was a moment I said, ‘Oh my goodness—we’re throwing away millions of bars of soap every day. And, literally, there are 9,000 children dying every day, and all they need is soap to wash their hands. They don’t even need clean water, according to these studies. They just need soap.'”

Seipler realized he could kill two birds with one bar of soap: reduce solid waste and give much-needed supplies to poorer people in developing countries.

Scaling up

Seipler clearly needed to scale beyond collecting soap on business trips and making recycled soap at home. He soon started using four cookers and a meat grinder to process the used soap, eventually graduating to a full kitchen operation. To test his process, he intentionally infected bars of soap with pathogens to see if steaming the soap would remove them.

Once Seipler determined that he could put used soap bars on trays, steam them for 30 to 60 seconds with restaurant steamers and remove 100% of all pathogens, his idea took off.

Today, his brainchild, Clean the World, uses proper facilities with more traditional soap-manufacturing machines that the organization has reordered to align with its own process. Nearly 100% of the soap Clean the World processes is turned into brand-new 1.75-ounce bars of soap that are packaged in boxes without any plastic wrappers. The result is pallets of soap that are either distributed through nongovernmental organizations like Children International or sent as humanitarian relief. The organization also has its own hand-washing programs in places like the Dominican Republic and Haiti, through which it teaches children how to wash their hands properly.

Since the organization’s inception, Clean the World has distributed nearly 70 million bars of soap in 127 countries. It does more than give out soap, though. It also collects and recycles bottled amenities (such as shampoo, conditioner, lotion and body wash) from more than 8,100 participating hospitality partners, focusing on two types of plastic bottles.

The first is small, single-use plastic amenity bottles that Seipler says are very hard to recycle. Clean the World converts those bottles into power via waste-to-energy methods, keeping bottles out of landfills and helping recover energy. The second type is large plastic bottles. Many big hotel chains are moving toward this format, Seipler notes, because it’s more environmentally friendly and sanitary than single-use plastic bottles that are refillable and thus more vulnerable to pathogen spread. Clean the World completely recycles any liquid left in those larger bottles; it’s turned into liquid detergent. The bottles themselves become large plastic bricks that can be used to make homes and other items.

Cleaning up the global waste crisis

In the context of the global waste crisis, Clean the World’s mission could not be more critical. Every year, more than 2.1 billion tons of waste is dumped across the globe. Most of that is neither recycled nor composted. For instance, according to the Environmental Protection Agency, the United States recycles or composts less than a third of its solid waste. About half of its solid waste ends up in landfills. Global plastic recycling rates remain under 10%. And the World Bank warns that annual global waste will increase by 70% to 3.4 billion tons by 2050 without intervening action.

All that waste pollutes our air, land and water. Hazardous chemicals leak into the soil, impacting human and nonhuman forms of life. Toxic substances enter the atmosphere, making the air harmful to breathe and amplifying the greenhouse effect that worsens climate change. And our oceans and groundwater bear the brunt of this waste too.

But Clean the World isn’t just taking action for the environment. It’s recycling and distributing soap with humans in mind. Crises ranging from the devastating earthquake that ravaged Haiti in 2010 to the ongoing Russian invasion of Ukraine have given Clean the World opportunities to deepen its impact in times of great need.

Pivoting during the pandemic

As Clean the World grew, Seipler knew he could not rely on donations as a long-term business model while providing a free service to hotels. So he started charging hotels a nominal per-room fee to have their used soap recycled by Clean the World. Recycling used soap is a key pillar of sustainability for Clean the World’s hotel partners, thereby enhancing their corporate responsibility efforts.

“It’s an employee giveback program and employee volunteer program,” he says. “It’s something they can share with their shareholders, with their stakeholders, with their volunteers.” In essence, Clean the World helps hotels reduce their landfill waste while helping save lives and improving their reputations as sustainable brands. It was a win-win.

It’s cheap—about 75 cents per room—for hotels to have Clean the World recycle their used soap, but all that revenue is dependent on people staying at hotels, and Seipler didn’t expect a global pandemic that would decimate travel in a matter of weeks. As it did to just about every organization, COVID-19 ravaged Clean the World’s operations. Since its primary revenue source is the hospitality industry, more than 90% of its revenue vanished when the pandemic hit.

“[I was] absolutely convinced that our business was done—that we were going to end it,” he says. “It was quite challenging.”

Seipler reflected on the deep irony of launching and growing a global organization centered around hand-washing that he feared would be destroyed by a pandemic whose most prevalent antidote in those early days was hand-washing. But rather than wallow in despair, he figured out how to pivot.

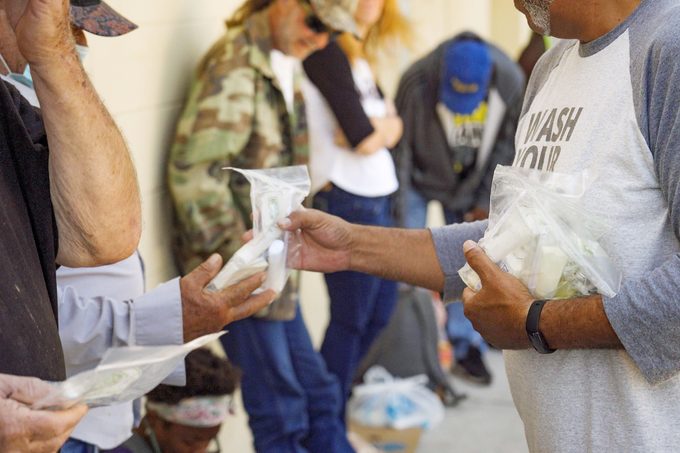

Before COVID-19, Clean the World partnered with companies for hygiene-kit-building events—a spin on the team-building retreat that helped people do good and ease their climate anxiety a tad. Seipler’s organization provided the materials, and employees of the partner company formed an assembly line to efficiently put together the kits.

During lockdown, Clean the World shifted the focus to fit the increasingly virtual world. It bundled all the components that would typically build 100 hygiene kits (think soap, shampoo, toothpaste and the like) into a single box. Those boxes were then shipped to the homes of employees who worked for some of Clean the World’s customers.

In essence, the organization adapted the assembly line model it previously used at corporate events for the social distancing era, giving customers’ employees and their families the ability to build hygiene kits and deliver them to places of need in their local communities or ship them around the world. Giving customers some agency in the process both uplifted people’s spirits when the whole world felt down and helped save lives while COVID-19 took away so many.

And a savvy business decision made a few years before the pandemic hit proved prescient in keeping Clean the World afloat. Instead of billing hotels and resorts directly on an ad hoc basis, the organization embedded some of its fees into the bulk purchases of soap and bottled amenities. This billing method provides a more consistent revenue stream. As such, while all of Clean the World’s partners who were billed directly stopped paying once the pandemic hit, the pivot toward embedded billing from bigger hospitality partners kept some cash coming in as the global economy shut down.

Saving lives and saving resources

As Seipler looks back on his organization’s trajectory, he can’t help but feel inspired. “It feels great that we’re an example and a model for others to be able to look at and say, ‘I can start a great company that helps other people, that employs the best and the brightest and the smartest, so we can go solve the world’s biggest issues,” he says.

Still, he’s clear-eyed about the organization’s early years—he started Clean the World as an entrepreneur, not an environmental activist on a principled mission to do good. But his career path has shaped his perspective on environmental and social justice. He now considers himself “in a category [of people] that did not think about things like climate change and other [related] areas,” but his 13 years at the helm of a leading social enterprise have shown him “what the power of human ingenuity and innovation can do with respect to solving those issues.”

And Seipler has big plans for the future. Geographically, he envisions international expansion into areas like mainland China, the Middle East, Africa and Latin America. Building on Clean the World’s pivot to hygiene kits during the pandemic, the organization also plans on distributing meal kits. And he sees a pressing need to help solve global water insecurity in the face of climate change, an issue he plans to address with Clean the World.

The ability to leverage his entrepreneurial passion and business savvy into a social enterprise that saves lives and saves resources has been life-changing for Seipler, whose career has shown him what people can accomplish when they work together. That insight has propelled him from working a proverbial childhood lemonade stand to running a global social enterprise that’s helping people and the planet, one recycled soap bar at a time.

Additional reporting by Alexa Erickson.

Sources:

- Shawn Seipler, founder and CEO of Clean the World

- Our World in Data: “Child and Infant Mortality”

- The World Counts: “Tons of waste dumped on the planet”

- Environmental Protection Agency: “National Overview: Facts and Figures on Materials, Wastes and Recycling”

- Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development: “Plastic pollution is growing relentlessly as waste management and recycling fall short, says OECD”

- The World Bank: “Global Waste to Grow by 70 Percent by 2050 Unless Urgent Action Is Taken: World Bank Report”