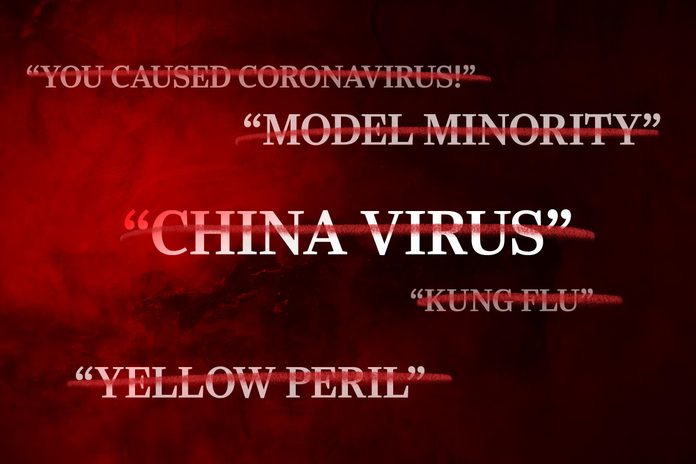

Anti-Asian Racism: How Language Fueled Hate Crimes and Xenophobia

Updated: Oct. 26, 2022

With people calling COVID-19 the "China virus" and "Kung flu," is it any surprise that anti-Asian hate crimes have been on the rise?

Some may argue that naming a disease for its place of origin (or supposed origin, as was the case with the Spanish Flu in 1918) used to be a common practice of the past. But in 2015, the World Health Organization issued guidance that called for the use of more neutral nomenclature for all naming of diseases. That hasn’t stopped people, including government officials, from giving nicknames with racist undertones to COVID-19, the virus that brought the world to a halt in early 2020.

Those terms, “China virus” and “Wuhan virus,” went viral in March 2020, after Secretary of State Mike Pompeo and Congressman Paul Gosar of Arizona first used them on Fox News and Twitter respectively.

That’s when anti-Asian hate crimes began to escalate. Less than a week later, a man at a Texas Sam’s Club stabbed three members of an Asian American family, including two young children, because he thought the family was “Chinese and infecting people with coronavirus.” On March 28, a 39-year-old woman in New York City was taken to the hospital for burn damage after a group of teens reportedly threw acid on her, proclaiming, “You caused coronavirus!” These are only two examples of the 47 reported incidents of anti–Asian American racism and hate crimes that took place in March after Pompeo first used the term “China virus.”

The violence against Asian Americans continued into the summer after then-President Donald Trump repeatedly used the term “Kung flu” in June—and the attacks haven’t abated. In all, nearly 3,000 reported racist incidents took place across the country from March to December 2020, according to Stop AAPI Hate, a national reporting center formed to track and respond to incidents of hate and discrimination since the pandemic began.

Sadly, in the months since Trump left office, the Asian American racism and violence against Asian Americans haven’t abated. In mid-March, six women of Asian descent were killed in a shooting spree at three different massage parlors in the Atlanta area.

A coronavirus by any other name

Words, especially when wielded by government officials, hold immense power. “Racist language and the racist concepts it denotes come to be seen as more acceptable when it enters into the public discourse,” says Lauren Hall-Lew, PhD, a sociolinguist at the University of Edinburgh. The more it’s used and the more places it’s used—be it in a formal speech, informal conversation, or in a tweet—the more it validates racism. “While there’s a long history of anti-Asian sentiment in the United States, anti-Asian language was more contained to private spaces before the spread of COVID-19 than it was afterward,” Hall-Lew says. In fact, a study in the September 2020 issue of the journal Health Education and Behavior found that anti-racist gains related to Asians made over the past 13 years were reversed in the three-week period following March 8, 2020.

“Yellow Peril” and the history of anti-Asian hate

The hate speech and crimes that followed in 2020 resurrected anti-Asian sentiment and stereotypes dating back to the late 1800s, when Asians were branded with the phrase “yellow peril.” The term encapsulates the racist ideology that Asians are disease-ridden and a threat to the American way of life.

Racially driven atrocities directed at Asian Americans over the course of the past 200 years are as horrific as they are numerous. The government even sanctioned some of these moves, for example with the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882, which banned Chinese immigration and prohibited existing Chinese immigrants from naturalization until its repeal in 1943. Around the same time the law was being repealed during World War II, 120,000 Japanese Americans were forced into internment camps, an atrocity that cemented Asian Americans as perpetual foreigners, no matter how long or how many generations their families have been U.S. citizens. That’s just one of the reasons why you should stop asking people of color where they are from.

Destructive myths of the “model minority”

Despite this bleak history, many Americans still hold the belief that all Asian Americans today are highly educated, economically successful, and professionally accomplished. This fallacy, called the “model minority myth,” breeds resentment and forces Asian Americans further into a space of “otherness.” The misconception is far from the truth. According to the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, Asian American unemployment rates skyrocketed 12.5 percent in the first five months of the pandemic—by comparison, the unemployment rate for the United States as a whole saw an 11.3 percent increase.

Historically, the model minority myth has been leveraged to divide communities of color and to squelch racial justice movements with the idea that there are “good” versus “bad” minority groups. The recent senseless acts of violence toward Asian Americans threaten to set the movement back by sparking racial tensions where solidarity is needed, especially in the context of the greater Black Lives Matter and anti-racist movement.

How to use language to help rather than to harm

Being an ally to those suffering from anti-Asian hate starts with simple steps. For starters, avoid using stigmatizing language when referring to COVID-19 and object when others around you do. Better yet, take a free bystander intervention training workshop to learn how to react safely in challenging situations. Teach children and others you have influence over to not associate the pandemic with a specific race or region. Listen to and check in with Asian American friends, neighbors, and colleagues. Validate their experiences and resist the urge to suggest that incidents are not race-driven. Just because one person doesn’t see or feel Asian American racism (or any racism) doesn’t mean that others experience the world the same way. Even after COVID-19 vaccinations become more widely available, it will take some time for the spike in anti-Asian sentiment to subside. Being a part of the solution will help the United States heal from this painful pandemic more quickly.

RELATED: Asian American–Owned Businesses to Support Right Now

Sources:

- Stop AAPI Hate: New Data on Anti-Asian Hate Incidents Against Elderly and Total National Incidents in 2020

- Health Education and Behavior: “After “The China Virus” Went Viral: Racially Charged Coronavirus Coverage and Trends in Bias Against Asian Americans”

- U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics