Bear Attack: The Story of Seven Boys and One Grizzly

Updated: Mar. 25, 2022

Seven high school students were near the end of their month-long survival course in the Alaskan wilderness, but the real schooling began when they came face to snout with the wildest thing of all.

At a shallow pool in a nameless creek, deep in the Alaskan wilderness, seven boys are laughing and lunging and splashing as they try to haze a pair of beleaguered little fish into their mosquito nets. Fishing is not allowed, but they took leave of their instructors several hours ago and are having their Lord of the Flies moment of fun.

At a shallow pool in a nameless creek, deep in the Alaskan wilderness, seven boys are laughing and lunging and splashing as they try to haze a pair of beleaguered little fish into their mosquito nets. Fishing is not allowed, but they took leave of their instructors several hours ago and are having their Lord of the Flies moment of fun.

Have a look at them: Joshua Berg, 17, from New City, New York, the group’s elected leader and most experienced outdoorsman. Noah Allaire, 16, from Albuquerque, New Mexico, a lifeguard and gifted student who skipped two grades in school and will be starting college in the fall. Sam Gottsegen, 17—“Gottsy” to the group—from Denver, avid snowboarder, affable and laid-back. Sam Melman, 17, a volunteer in a New York hospital’s intensive care unit. Victor Martin, 18, a muscular basketball player from a tough part of Richmond, California. Shane Garlock, 16, from Pittsford, New York, photographer and cross-country runner. And Sam Boas, 16, from Westport, Connecticut, ardent cook and certified emergency medical responder.

They are students of the prestigious National Outdoor Leadership School on a month-long course during summer vacation from high school. It’s 7:30 in the evening on July 23, 2011, and they’ve spent the past 24 days backpacking through the rugged western Talkeetna Mountains with three instructors, learning leadership and outdoor skills, including first aid. They’re now about 40 miles northeast of the nearest town, Talkeetna, separated from any sign of human habitation by miles of rough, trackless country. This is the last leg of the trip, when the students are cut loose to find their own way to a train track 24 miles away, where they will rendezvous with their instructors in three days. Until then, they have no way of communicating with their instructors or with the outside world. They are truly alone. Earlier today, just before the boys set out, one of the instructors looked at them and, grinning, left them with this advice: “Don’t die.” It’s taken the better part of an hour, but the fishing expedition has been a success, and the boys continue their hike up the stream with the pair of tiny rainbow trout in tow. They’re walking single file directly in the cold water, using the creek as a trail because the land here is covered in scrub alder and willows that make travel nearly impossible. Berg, Gottsegen, and Allaire are in the front. The stream may make for easier walking than the land, but it is full of bends, some of them so tight that you can’t see around them to know what you’re about to walk into.

It’s taken the better part of an hour, but the fishing expedition has been a success, and the boys continue their hike up the stream with the pair of tiny rainbow trout in tow. They’re walking single file directly in the cold water, using the creek as a trail because the land here is covered in scrub alder and willows that make travel nearly impossible. Berg, Gottsegen, and Allaire are in the front. The stream may make for easier walking than the land, but it is full of bends, some of them so tight that you can’t see around them to know what you’re about to walk into.

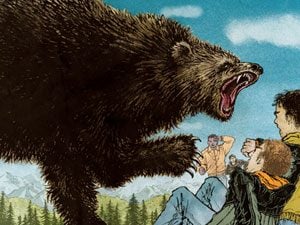

Berg rounds one such curve and sees what looks like a bale of hay just 30 feet in front of him. He has time only to turn around and scream, “Bear!” before the grizzly closes the space between them, rises on its hind legs—towering seven feet tall and weighing about 500 pounds—lunges, and flattens him. With a horrific roar, it goes straight for Berg’s head, chomping down on his skull with an audible crack. The others scream and scatter. As part of “grizzly protocol,” they have been taught to stand their ground, but this is too close, too sudden, too violent. And the bear is too big, too loud, too real—the earth booms each time it slams its paws to the ground. They don’t even have the time or wherewithal to pull out the bear repellent three of them are carrying.

There is a ridge on the right side of the stream, and most of the other boys scramble up it through the brush. Berg’s awful screaming prompts Sam Gottsegen to stop and look back at his friend. The bear still has Berg’s bloodied head in its teeth and is shaking the 180-pound boy like a flag as it gouges at his torso with its claws. Martin has paused near Gottsegen. “Is Josh being eaten?” he gasps.

Allaire is hiding on the left-hand shore, about 30 feet below. Garlock, Melman, and Boas are higher up on the hill, some of them screaming in panic, flattening themselves beneath the scrub willows. Gottsegen faces a dilemma: Do I run toward my friend who’s being attacked by a grizzly bear and basically sacrifice myself? Or do I run in the opposite direction? But it doesn’t matter, because now here comes the bear toward Gottsegen, its snout twisted furiously, a light-brown blur so fast that Gottsegen can take only a couple of steps before it slams him. He hits the ground and rolls and comes up on his knees screaming, and the bear snarls and grabs his head in its teeth and there is another loud crunch. Gottsegen somehow pulls himself clear and runs a few steps, but the bear flattens him again, biting his hand, gnashing at his neck, chest, arm, and back, and slamming its claws into his rib cage with enough force to puncture his lung.

He hits the ground and rolls and comes up on his knees screaming, and the bear snarls and grabs his head in its teeth and there is another loud crunch. Gottsegen somehow pulls himself clear and runs a few steps, but the bear flattens him again, biting his hand, gnashing at his neck, chest, arm, and back, and slamming its claws into his rib cage with enough force to puncture his lung.

If Hollywood were to film a bear attack, there would be close-ups of the animal’s fierce eyes, its breath would fog the lens, we would see the awful fangs closing in. The reality is more like what you would see if the camera were slapped violently to the ground from behind and then kicked around in the bushes for 30 seconds—maybe a glimpse of fur, but mostly a blind confusion. You are being overwhelmed by an animal that has been clocked at 30 miles an hour and is capable of taking down smaller moose or caribou. There is remarkably little pain—endorphins kick in, and you hear your own skull crunching and think, Where is the pain? Your whole life may not pass before your eyes, but one part of you is busy trying to convince the other that you’re about to die.

There is a quiet moment. The bear has disappeared, and Berg’s screaming has changed to moaning. Allaire is still hiding on the shore. He peers up the hillside. Garlock and Boas are hunkered down, refusing to look, but Melman is standing and surveying the scene, wide-eyed. Allaire makes eye contact with Garlock. Where’s the bear? Allaire mouths silently. Garlock gives an exaggerated shrug. Allaire slips out of his backpack and runs forward to help Berg. The bear bursts out of nowhere to blindside him, razoring Allaire’s scalp nearly off with the first swipe of its paw. It bites into Allaire’s torso—bottom teeth in the back, top teeth under the armpit—lifts him in its mouth three feet off the ground and shakes him, roaring and growling, then drops him. Now it rises again onto its hind legs, astonishingly tall, as if ready to slam its front paws down and finish Allaire, but it hesitates when it notices Boas, Melman, and Garlock up on the hill. It hops over the bleeding Allaire and flees.

But it blunders into Martin, who is standing near Gottsegen, and seizes his left calf in its teeth. Martin somehow kicks his way clear, and the grizzly darts off over a hillock.

“It’s gone!” Melman shouts.

A cold rain begins to fall. “Beacon! Beacon!”

“Beacon! Beacon!”

Berg is alive and crawling toward his backpack, which contains an emergency personal location beacon that will signal their GPS coordinates by satellite to the Alaska Rescue Coordination Center. Allaire stands wobbily, drenched in blood, and runs to Berg. “Get the beacon,” Berg says.

Melman and Boas come down off the hill to help. Boas cradles Berg’s mangled head in his lap and tells his friend to keep still. None of them has ever used the beacon before, so they wipe Allaire’s blood off the laminated instructions and study them together. There’s a red plastic pull tab that needs to be removed, and it’s stuck fast. They wrestle with it until it breaks. Using Garlock’s beloved lock-blade knife, which he’s dubbed Betsy, they pry free the plastic tab. The beacon slides open, and an antenna unfurls. Someone presses the On button, and the group huddles over the device, watching the LED display to be sure their GPS coordinates have been sent.

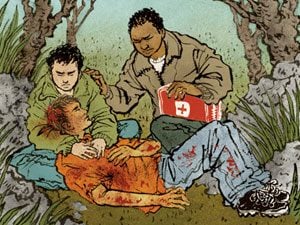

Gottsegen has stumbled to a small clearing and fallen there, crying out for help, his torso pierced in several places. When Allaire inspects Gottsegen’s injuries, he’s shocked to discover a sucking chest wound: The bear’s claw has passed between Gottsegen’s ribs and into his chest cavity, collapsing his lung. Now each time Gottsegen draws a breath, he sucks wind through the hole in his torso, the air-infused blood burbling at the surface. If the wound is not properly treated, the other lung will collapse, and Gottsegen will die. Allaire tears apart a garbage bag and flattens a piece of its plastic over the wound, making an airtight seal, then wraps Gottsy’s torso with an elastic bandage and keeps pressure on the dressing—it’s textbook field treatment for such a wound, crucial for stabilizing the air pressure in the chest cavity.

Sam Boas is still holding Joshua Berg’s head, trying to keep his head and back stable in case he’s suffered brain or spinal cord injuries. Berg has been utterly wrecked by the bear. His legs are going numb, his skull is fractured, and the flesh of his head shredded so violently as to render him unrecognizable. He’s bleeding everywhere.

“Get my camera,” Berg says.

“Why?” Melman asks.

“I need to make a video.”

Melman finds the camera and shoots a heartbreaking video of a mutilated Joshua Berg saying a tearful goodbye to his family and friends. “I love you all, and I’m sorry I can’t be with you,” he tells them.

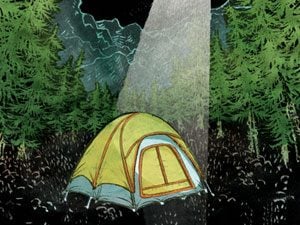

When the video is over, Melman leads Berg in the Shema Yisrael, a Jewish prayer traditionally sung as a person’s last words. Shane Garlock has set up a four-man tent, and they carry Gottsegen and Berg inside to get them out of the rain. All seven crowd into the shelter, where the uninjured donate most of what they’re wearing to warm Gottsegen and Berg, whom they’ve bundled into sleeping bags. Allaire has paused only long enough to wrap his own flayed scalp in gauze and then gone back to tending to the others.

Shane Garlock has set up a four-man tent, and they carry Gottsegen and Berg inside to get them out of the rain. All seven crowd into the shelter, where the uninjured donate most of what they’re wearing to warm Gottsegen and Berg, whom they’ve bundled into sleeping bags. Allaire has paused only long enough to wrap his own flayed scalp in gauze and then gone back to tending to the others.

The tent has become a field hospital, with Melman the ICU volunteer, Boas the EMR, and Allaire the lifeguard running the show. Boas devotes his efforts to keeping Berg’s head stable. Garlock and Martin do what the others tell them to: Keep pressure on Gottsy’s chest. It’s been ten minutes, so take a pulse. Move Josh’s feet to make him more comfortable. Lay across Berg and Gottsy to keep them warm.

They all pee into their water bottles and tuck them into Gottsegen’s and Berg’s sleeping bags for warmth.

Suddenly, Allaire speaks up. “I can’t feel a pulse on Gottsy.”

“Try his radial pulse,” Boas says.

Nothing.

“Try the brachial,” Melman says.

“I still can’t feel it.”

Allaire tries the femoral pulse, in the groin. There is a long, terrifying silence. “OK,” he says. “He has a pulse.” Everyone in the tent exhales with relief.

“Where is that helicopter?” Gottsegen whispers. Surprisingly, it is not his chest wound that pains him the most but the ring finger of his right hand, which the bear bit clean through, the tooth stabbing up through the fingernail.

“It’s coming,” Boas says.

The group hunkers down to wait for help. Rain taps the roof of the tent. Hours pass, and the temperature drops into the low 50s. Everyone is shivering uncontrollably. The blinking of the beacon offers periodic snapshots of the tent walls and floor, smeared and pooled with the boys’ intermingled blood.

A little after 2 a.m.—more than five hours after the bear attack—the tent is blasted by the glare of a floodlight, and its walls lean in the rotor wash. A Helo 1 A-Star helicopter settles among the brush some 30 yards away, and an Alaska state trooper steps down and approaches the campsite.

The trooper is a transplanted New Zealander named Michael Shelley. He sizes up the situation and determines that there isn’t enough room for everyone on the small aircraft. Nor is it equipped for severe trauma patients like Gottsegen and Berg. Shelley insists that Garlock and the walking wounded—Allaire and Martin—leave with the pilot. It’s up to the boys to decide which one of them will remain behind with Shelley, Gottsy, and Berg to wait for a larger helicopter to medevac them out. Melman volunteers, but for Sam Boas, the EMR, who has not left Berg’s side all these hours, there’s no debate: He will be the one to remain behind.

Minutes later, the others bid a tearful farewell to their friends, saying things that most guys would never dream of saying to one another, like “I love you.”

Three hours later—eight hours after their ordeal began—an Alaska Air National Guard Sikorsky HH-60 Pave Hawk Helicopter thunders to a landing near the tent. Within seconds, helmeted elite pararescuemen have burst into the tent and begun working on Berg and Gottsegen, trundling them into orange superinsulated rescue bags. A crewman leads Boas out of the tent and into the helicopter. Soon Gottsegen, Berg, and Shelley are in the helicopter with him. The chopper lifts up, as if drawn straight up on a string. Boas gets one last look at the wreck of a campsite that lies below, and then they’re off. Only 12 minutes have passed since the chopper landed, and now they’re racing across the mountains that it has taken his group weeks of struggle to cover on foot, and the little makeshift campsite is once again an insignificant speck on a tight bend of an anonymous brook in the incomprehensibly vast Alaskan bush.

The bear was never found, and the reason it attacked is still a mystery. It might have been protecting its kill site or maybe a cub. Whatever the reason, experts were stunned—it’s virtually unheard of for a grizzly to attack a group larger than four.

All the boys survived. Victor Martin was treated for the bite on his leg and released. Sam Gottsegen suffered broken ribs, and his lung needed to be reinflated (his chest cavity had been punctured in not one but three places); he spent eight days in the hospital and is now nearly fully recovered. He even went snowboarding over the winter.

Surgeons worked eight hours on Joshua Berg’s head, inserting a titanium plate and bone graft in the boy’s skull. Berg spent a total of 20 days hospitalized. He is well now, his appearance little changed but for some scarring. Noah Allaire’s scalp required surgery to be stapled back in place. Doctors discovered that one of his lungs had been punctured by the bear’s tooth, but, though it leaked some air, it healed on its own.

Allaire spoke to his parents, Patricia Allaire and Scott Newland, from his hospital bed. They had

already talked to the troopers, but all they knew was that there had been a bear attack and Noah was injured.

“Mom, Dad,” he said. “I’m all right.”

“It sounds like you were really brave,” his mother said between sobs.

That’s something all seven of them would hear, a lot, in the weeks ahead.