The 6 Biggest Controversies of Queen Elizabeth’s Reign

Updated: Jan. 05, 2023

The death of Queen Elizabeth II has resurrected discussions about her greatest scandals—from Princess Diana's death to British colonialism

The Reader’s Digest Version:

|

While much of the world mourns Queen Elizabeth’s death, a growing number of people are pointing out the darker aspects of the monarchy and the controversies associated with the longest-reigning monarch—from tabloid gossip about her late daughter-in-law to travesties like colonialism and climate disaster under her reign. Many also point to the fact that part of Queen Elizabeth’s net worth and many of the crown jewels are directly tied to slavery in the colonies.

While young Queen Elizabeth inherited an empire known for its colonization, during Queen Elizabeth II‘s reign, in addition to much of the good she did around the world, she made a number of questionable decisions that put her under scrutiny.

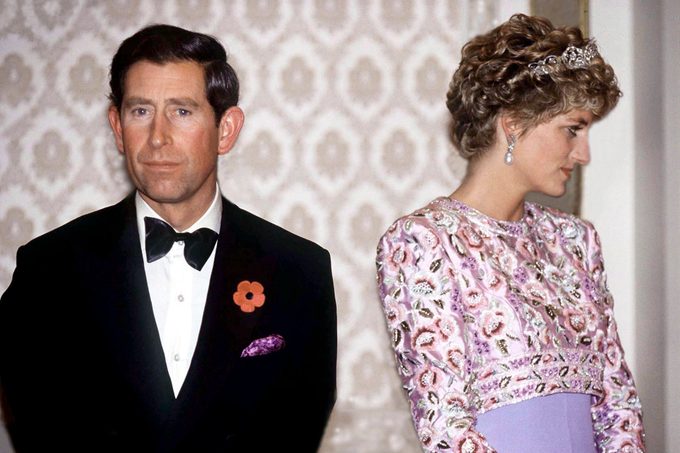

Prince Charles and Princess Diana’s divorce

Like any world leader, Elizabeth faced plenty of criticism and upheaval. Perhaps the most famous scandal during her reign had to do with the marriage, divorce and death of Princess Diana—aka the people’s princess. When Prince Charles married Diana Spencer, the queen was supposedly displeased. But things only got more tense when Charles divorced Diana, which many royal experts argue led to Diana’s demise.

In 1993, shortly after Charles and Diana separated, someone leaked a scandalous phone call between Charles and his “friend” at the time, Camilla Parker Bowles, that came to be known as “Tampongate,” in which Charles told Camilla some of his most intimate fantasies. Both Charles and Camilla were married to other people at the time.

In 2005, Charles remarried Camilla—now the queen consort—much to the public’s dismay.

Princess Diana’s death

In 1997, Princess Diana died tragically in a car accident, and the queen stirred more controversy by refusing to fly the flag at half-mast in her honor. (She eventually relented and made a lovely statement in tribute to Diana.) But while the drama surrounding the two was tabloid gold, here’s the truth behind Queen Elizabeth and Princess Diana’s relationship.

Prince Harry’s exit

Prince Harry—one of Queen Elizabeth’s grandchildren—and his wife, Meghan Markle, stepped down from royal life in 2020. The couple moved to Canada, in part due to racism Markle experienced from the royal family.

Of course, we’ll never know exactly what went down behind closed doors. Publicly, Elizabeth stayed mum, and the couple named their daughter Lilibet, a nod to Elizabeth’s childhood nickname. Plus, Meghan Markle and Queen Elizabeth maintained a special relationship.

Prince Andrew’s sex-trafficking scandal

Elizabeth’s third child was forced to step down from his royal duties after being accused of sleeping with a teenage victim of Jeffrey Epstein’s sex-trafficking scandal. Though the victim sued Prince Andrew, the U.S. sexual assault case was settled out of court.

The “annus horribilis”

“The horrible year” was Elizabeth’s term for 1992, the year three of her four children divorced and Windsor Castle nearly burned down. That alone would have been enough, but the events sparked international controversy about the royal family’s double standards on extramarital affairs and the extreme wealth of the monarchy—and of Elizabeth personally. (She was supposedly worth around $430 million dollars at the time of her death.)

One look at the queen’s body language that year, and it’s clear she truly considered it an annus horribilis.

The connection to colonialism

Colonialism happens when one nation subjugates another, taking control of the population and exploiting it while forcing the conquered people to accept the colonizing country’s language, religion and culture over its own native ideas. But that’s a fairly sterile definition for a very bloody practice. “There’s no disputing that colonialism, including British colonialism, is built on slavery and human suffering,” says Nicoletta Gullace, PhD, a historian at the University of New Hampshire with a focus on British history and an expert on the royal family.

At some point in history, every major civilization has engaged in some form of colonialism. Just look at the Americas: Britain, Spain, France, Portugal and other European countries colonized lands indigenous people had been living on for centuries. However, Britain’s history of colonialism is by far the most talked about controversy connected to the Queen’s death.

What is the history of colonialism in the British Empire?

You may have heard the phrase “The sun never sets on the British Empire,” and that wasn’t an exaggeration. At its height in 1922, the British Empire was the largest empire the world had ever seen, covering one-quarter of the earth’s land and ruling more than 458 million people. With a worldwide population of just under 2 billion, that meant about one in five people living on the planet was a British subject.

Many of those subjects weren’t thrilled with the situation, particularly because they’d become part of the empire by force, through colonialism. Britain tore countries apart, forced their people into slavery and exploited natural resources—all in the name of the crown. These things have left lasting social, cultural and financial scars, all of which are once again in the spotlight.

“The empire was deeply destructive of Indigenous peoples and their economies, societies and cultures,” says Susan Kent, PhD, an expert on the British Empire, professor emerita at the University of Colorado Boulder and author of A New History of Britain Since 1688. Some of these colonies included the countries known today as Afghanistan, Australia, the Bahamas, Botswana, Canada, Fiji, India, Ireland, Malaysia, New Zealand, Pakistan, Sri Lanka and nearly all of Africa.

And Americans shouldn’t forget the role of British colonialism in their own backyards. The empire colonized Indigenous land to establish the 13 original colonies, and the United States gained its independence from Great Britain only after a bloody war.

Even though it was the largest empire the world had ever known, it certainly wasn’t the longest lasting. Its major growth occurred between the mid-1800s and the 1920s. But by 1947, India, “the crown jewel of the British Empire,” was granted independence, partly as a deal for assisting the Allies in World War II and partly because of Gandhi’s national independence movement. India was leaving, whether Britain liked it or not, and other countries began planning their own independence.

King George VI, Queen Elizabeth’s father, saw the writing on the wall and formed the Commonwealth, allowing former colonies to be independent while working “freely and equally” with the United Kingdom.

What role did Queen Elizabeth play in British colonialism?

While the queen was an important figurehead, the queen’s governing power was limited. “The queen didn’t rule—she reigned,” says Gullace, adding that regardless of her personal feelings, she had to function within the British political system as it existed at that time.

When Elizabeth was crowned in 1952, she made it a priority to tour the entirety of the empire. Her “walkabouts” helped create a warmer relationship with many of the colonies and made her the most widely traveled head of state in the world. During her tenure, she worked tirelessly to expand the Commonwealth, eventually building it into the world power it is today—the second-largest international organization after the United Nations.

But while she may have simply inherited the imperialist system, she did play a part in what happened (or didn’t) afterward. And some of that was pretty grim.

For instance, even though Britain officially abolished slavery in 1833, the crown was still reimbursing slave owners for the loss of their “property” during Elizabeth’s reign. Even worse, the haphazard way the British left many of the colonies led to decades of poverty, bloody conflicts and corrupt regimes.

Was this her fault? Not directly, but that also doesn’t mean her hands are totally clean, says Kent, who co-authored a book about Britain’s colonization of Africa, titled Africans and Britons in the Age of Empires, 1660–1980. The year Elizabeth became queen, the Mau Mau insurrection in Kenya began. The British military, under her reign, responded brutally against Mau Mau fighters and portions of the Kenyan population. To quell the anti-imperial insurrection, Britain put millions of Kenyans into detention camps, where they were tortured.

“She did not order or implement the actions [but] appears to not have done anything to prevent or constrain them either,” says Kent. “On the contrary, she celebrated the empire, remaining silent, publicly at least, while thousands and thousands and thousands of people in Africa and South Asia suffered at the hands of colonial administrators.”

What it comes down to, she says, is this: “The monarchy itself was and is so deeply wrapped up in the empire that it is difficult to extricate it from the actions and consequences of imperialism.”

Decolonization of the empire

Much of Queen Elizabeth’s reign happened after British colonization, and more than 55 countries—including nearly all the colonies of Africa, the Pacific islands and the Middle East—gained their independence while she was queen. That’s why she’s credited with decolonizing the empire.

“Decolonization did not undo much of the damage wrought by colonization,” says Kent, explaining that the institutions, infrastructure and economies of the former colonies had been set up by the British to benefit the empire. The new African nations inherited these things, but they were still tightly bound to England, and many of them barely functioned at all. One example: Placing a telephone call from Nairobi to London was simple, cheap and efficient; placing a call from Nairobi to Dar es Salaam was fraught with difficulties.

“African leaders had to absorb and pay for the huge bureaucratic apparatus put in place during colonization, and their populations did not fare well,” she says.

A symbol of colonialism

Queen Elizabeth chose to be the public symbol of the British Empire, knowing exactly how powerful symbols can be, says Gullace.

“For better or worse, the queen represented the empire—she did so purposefully—both to Britons and to formerly colonized peoples,” Kent says. “She may not have possessed formal political power, but she did wield great influence, and she self-consciously presented herself as the head of the empire/commonwealth.”

Why has Queen Elizabeth’s death sparked debate about the monarchy?

The debate today isn’t so much about the monarchy itself, but rather Elizabeth’s connection to colonialism. Should she be held personally responsible for an institution she inherited and actively worked to dismantle? This question doesn’t have a simple answer.

“I feel it’s unfair to tar the queen for what her predecessors (members of the royal family tree) did,” says Gullace. “We need to be careful about judging the past based on present standards. She was humane and egalitarian and did what she could with the power she had.”

Gullace cites the famous example of the queen going up against then-Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher over Britain’s response to South African apartheid. In the late ’80s, when member nations of the Commonwealth agreed on economic sanctions against South Africa in opposition to the country’s apartheid, Britain was the sole holdout. The queen took issue. As the New York Times reported on July 20, 1986, “The queen reportedly also believes that Mrs. Thatcher’s Conservative Party Government lacks compassion and should be more caring toward less privileged members of society.”

But do her good actions negate the long-lasting consequences of her more controversial acts? “It’s understandable that those negatively affected by the impacts of British imperialism and colonialism would direct their pain, anger and hurt at Queen Elizabeth, or at least at the monarchy,” says Kent.

Even the former colonies themselves are divided on the issue. Leaders of Kenya and South Africa released official statements praising the queen and paying tribute, while politicians and citizens posted poignant messages about all the pain the empire caused. “We do not mourn the death of Queen Elizabeth,” is the beginning of a message from an opposition party in South Africa.

And this response isn’t limited to Africa. There has been a slew of social media posts highlighting Irish discontent with the queen—one of the most popular is a troupe of Irish dancers doing the jig to “Another One Bites the Dust” in front of Buckingham Palace—that it’s become its own class of anti-Queen Elizabeth meme.

Further, the online debate has renewed public interest in official or unofficial reparations for people victimized by British colonialism. While it seems like a good idea, it gets complicated quickly, says Gullace.

Do aristocratic families pay it back? Does it come from the government coffers (and thus become a tax on the average Briton)? Do you give back objects, like artwork, antiquities and jewels? (There’s already a public call for the return of the Koh-i-noor diamond from India and the Cullinan Diamond from Africa, both worth about $400 million.) Or do you take it further, transferring wealth? How will Britain decide which former colony gets reparations first and which type?

“There are billions of pounds tied up in postcolonialism, and the bottom line is: What price is a society willing to pay to heal?” Gullace asks.

Kent sees a compromise. “I would indeed like to see King Charles III return the jewels and other items seized from colonies; it would go a long way to announce a new way of thinking about former colonies,” she says. “It would be symbolic and not make much difference in the actual lives of formerly colonized peoples, but symbolism can be potent.”

What might Queen Elizabeth’s death mean for the future of the monarchy?

All this controversy leads to the inevitable question: Is this the end of the monarchy in England? And will the history of colonialism be a factor?

“It’s not clear to me that Charles will bear the burden of association with colonial violence, but he also doesn’t command the emotional connection with people that Elizabeth did,” says Kent. “If the reception of Prince William and Princess Kate in Jamaica is any indication, many of the [former colony] nations that accepted the British monarch as head of state will likely not do so in the future.”

On the other hand, Gullace thinks that now that Charles is king, the monarchy will likely continue for emotional and economic reasons. “Britons still want the monarchy, and many feel emotionally attached to it as a fundamental thing that makes them unique,” she says. “The monarchy is also a huge draw for tourists, who bring a lot of money into the economy.”

How will the queen be remembered?

It remains to be seen how the history books will be written now that Queen Elizabeth has passed away. But even as Elizabeth was a symbol of colonialism, she was also a powerful symbol of stability and safety—one that Britons need more than ever these days.

“The loss of Queen Elizabeth is deeply, deeply felt by the vast majority of Britons, who see in her a sign of stability and continuity in a world gone haywire around them,” says Kent. “She, and the royal family generally, may seem to be the only stabilizing force in a country faced by economic ruin and climate disaster. Brexit, the pandemic, irresponsible politicians, environmental catastrophe and an upcoming winter of insufficient heating and food—these are what Britons are up against. Celebrating the life of a woman who seemed never to wobble, not even for a second, may provide solace and relief against the buffeting of a future that looks very bleak.”

Sources:

- Nicoletta Gullace, PhD, professor at the University of New Hampshire with a focus on British history and an expert on the royal family

- Susan K. Kent, PhD, professor emerita at the University of Colorado Boulder, an expert on the British Empire and author of A New History of Britain Since 1688: Four Nations and an Empire

- National Geographic: “What Is Colonialism?”

- Reuters: “Mixed feelings among some in Africa for Queen Elizabeth”

- New York Times: “Newspaper Says Queen Is Upset by Thatcher”

- Esquire: “What Was the Tampongate Scandal and Why Isn’t ‘The Crown’ Covering It?”