What Is Environmental Racism, and How Can We Fight It?

Updated: Aug. 02, 2022

Environmental racism isn’t a new problem, but it often flies under the radar—with disastrous consequences. Here, experts explain what it is and how it affects our world.

The Reader’s Digest Version

|

What’s it like where you live? Does the air smell fresh? Do you have a green space somewhat nearby that you can enjoy? Is your water clear and clean? These seem like basic requirements for any living situation—and they should be. But they’re not the reality for certain communities in America that are affected by environmental racism.

While environmental racism may not sound that critical, its effects can be devastating—even lethal. “Right now, your ZIP code is the most important predictor of health and well-being,” says Robert Bullard, PhD, who is known as the father of environmental justice for his decades of work in the space. “You tell me your ZIP code, and I can tell you how healthy you are.”

But what is environmental racism, exactly, and how did it take hold in modern society? It has a long history that’s intricately connected to both discrimination and White privilege, and it’s hard to root out, similar to the institutional racism called out by Critical Race Theory. But anti-racism activists are increasingly sounding the alarm to change policies and improve the quality of life for millions of Americans. Reader’s Digest spoke to experts to better understand environmental racism, how it’s contributing to both inequality and climate anxiety, and what we can do to make a difference.

What is environmental racism?

Environmental racism is “discrimination in the application of environmental laws,” according to Bullard, who is also a professor of urban planning and environmental policy at Texas Southern University. In this common yet under-acknowledged form of structural racism, environmental policies favor White and upscale communities and prioritize their health and well-being over non-White, poorer communities (for example, by placing undesirable things such as incinerators near those poor, largely minority communities). As a result, pollution—and its resulting negative health and socioeconomic effects—overwhelms these disadvantaged areas.

The term “environmental racism” was coined in the early 1980s by civil rights activist Benjamin Chavis, after the state of North Carolina dumped soil laden with cancer-causing chemicals in a poor Black farming community. That type of decision, made by governments and corporations, is just one type of environmental racism; the term also encompasses housing policies, including proximity to manufacturing plants, and an unequal distribution of resources.

A 2021 study published in the journal Science Advances found that people of color in the United States are exposed to dangerous air pollutants from all major sources—including construction, power plants, industry, cars and trucks, and agriculture—at much higher rates than their White peers. This group accounted for 75% of the total exposure in the study, even though they comprised significantly less of the population.

What is the history of environmental racism?

In the early 1900s, zoning laws and restrictive racial covenants (exclusionary clauses placed on home deeds) functioned like an impermeable, invisible fence, effectively keeping people of color out of affluent White neighborhoods. Then, in the 1930s, came redlining—the systematic denying of financial services like mortgages and insurance policies to members of a community based on its racial makeup.

While the Fair Housing Act of 1968, signed into law by President Lyndon B. Johnson, outlawed both redlining and race-based covenants, their effects were long-lasting. Redlined communities, which had been deprived of financial resources for so long, fell further behind in terms of home ownership, business equity and infrastructure. They were also denied certain environmental protections, like green space and higher ground to live on, which could protect them from natural disasters.

Hurricane Katrina exposed just how problematic those disparities could be. BIPOC, who lived in congested communities in the most hazardous part of the city (the Lower 9th Ward), were swept away when storm surges broke down 50 levees and floodwalls. A majority of those who died were Black, and according to one study, the Black mortality rate was up to four times that of White residents in the area.

“What Katrina uncovered was a truth that those of us fighting [against] environmental racism already knew,” Bullard wrote in his book Race, Place and Environmental Justice After Hurricane Katrina. “That truth is that minorities and the poor are more likely than all other groups to be underprepared and underserved and to be living in unsafe, substandard housing.”

Why is environmental racism important?

Environmental racism severely hampers the quality of life for millions of people of color. Policies enacted in these communities, outright neglect or diminished resources have led to pollution that caused or compounded rates of asthma, cancer, infertility and other health conditions. According to Bullard, “the communities and the states that have a history of racism and discrimination that was codified in law—from slavery to Jim Crow segregation—generally have the worst pollution, the worst economic inequality and the worst health.”

A 2017 study from the Clean Air Task Force found that Black people are exposed to 38% more polluted air than White people and are 75% more likely to live adjacent to a plant or factory. That same study also found that Black people are nearly four times as likely to die from exposure to pollution as White people. These adverse conditions can have a particularly detrimental impact on women and children. A 12-year analysis of more than 32 million births by the JAMA Network found a link between air pollution and climate change—both of which are more likely to affect Black mothers and babies—and adverse pregnancy outcomes, including premature birth, low birth weight and stillbirths.

Experts worry that the situation is about to get more dire. The Supreme Court’s June 2022 ruling in West Virginia v. EPA limits the EPA’s ability to regulate the emissions of power plants—many of which are located in BIPOC communities—on a national level. If left unchecked, greenhouse gas emissions could skyrocket, causing a domino effect of climate-related catastrophes such as record heat, sea-level rise, increasingly frequent and intense hurricanes, and more. While everyone would benefit if the United States emulated the environmentally friendly practices of the world’s most sustainable countries, communities of color could see some of the most immediate benefits.

What are examples of environmental racism?

Environmental racism can be insidious, always there but not fully understood until shocking facts are brought to light. According to Mustafa Santiago Ali, vice president at the National Wildlife Federation and a 25-year veteran of the Environmental Protection Agency who cofounded the agency’s environmental justice office, there are numerous examples from coast to coast. Here are just a few.

“Cancer Alley,” Louisiana

An area located between New Orleans and Baton Rouge has earned the dubious name of Cancer Alley because its cancer rates are significantly higher than in other parts of the country—in some spots, it’s 50 times the national average and among the top 10 cancer zones in America. About 1.7 million people call this 100-mile stretch along the Mississippi River home—and so do 150 petrochemical plants and refineries. Many of those plants were built on the sites of former plantations, and the surrounding communities are predominantly Black and impoverished.

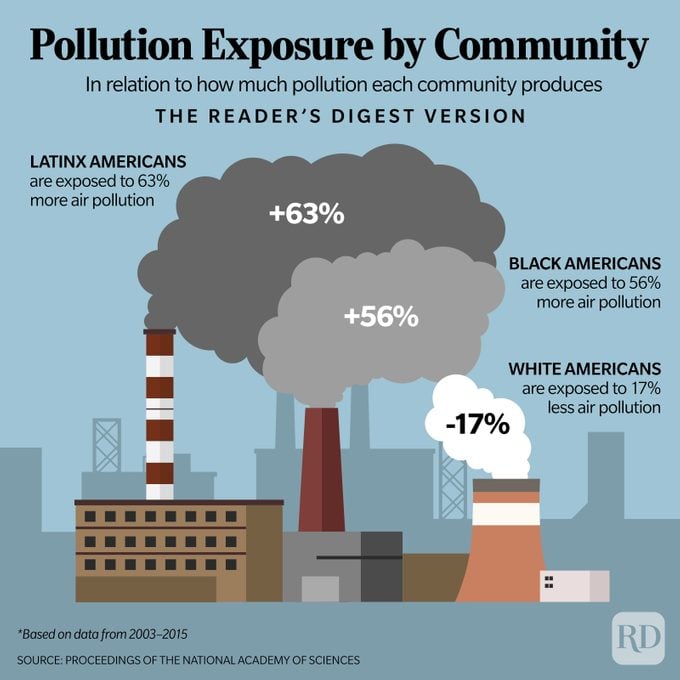

Studies have shown that, in general, Black residents are exposed to 56% more fine particulate pollution in relation to their consumption of goods and services, while White residents have 17% less exposure compared with theirs. In Cancer Alley, specifically, the cancer rates in the Black population are significantly higher than in the White one, with some showing a 16% disparity. Even so, plants are still being built, toxins are being emitted at record numbers and there’s been insufficient action to address the situation and even gather proper data.

Flint, Michigan

In one of the worst cases of environmental racism in recent years, officials looking to cut costs in 2014 provided water contaminated with lead and bacteria, the result of years of dumping from a local auto plant, to the residents of Flint, a poor and predominantly Black city. These actions resulted in at least 12 deaths, 90 cases of Legionnaire’s disease and 10,000 children poisoned by high exposure to lead, leading to learning disabilities as well as physical health issues. Testing showed that the city’s water exceeded the EPA’s classification as “hazardous waste,” and one home’s drinking water had 25 times the amount of lead deemed safe.

Officials not only approved this water for the community—they also ignored numerous red flags and insisted the water was safe. And the issue is still going on. Eight years after it was brought to the public’s attention, 10,000 pipes have been replaced, but there are still 1,800 more to go.

A town that neighbors Flint was hit even harder, according to Ali. “Benton Harbor has higher levels of lead in their water than Flint, Michigan, did,” he says. “And we know the huge amount of kids and others who had to deal with being lead poisoned.”

Dickson, Tennessee

Bullard considers this example of environmental racism among the most egregious. It centers on the Holt family, who lived in the small Tennessee town of Dickson. Multiple family members died or got sick as the result of a company illegally dumping drums filled with trichloroethylene (TCE), an industrial solvent and known carcinogen, about 500 feet from the family’s home. Beginning in 1988 and continuing for 12 years, the drums leaked the chemical into well water consumed by the family and their neighbors.

“The county is only 4.5% Black, but 100% of its waste, garbage and hazardous materials was sent to this one area,” says Bullard. And the way the matter was handled in the Black and White communities varied greatly, illustrating a glaring example of White privilege.

“The Black community basically were sent letters that said, ‘We found a chemical in your wells. It’s OK to drink it. It’s OK to bathe with it. It’s OK to cook with it,'” explains Bullard. “The same letters were sent to White communities, [but they said], ‘Don’t drink, don’t bathe, don’t cook with the water.'” After 48 hours, officials took the White families off the well water, but the Black families dealt with this problem for a dozen years, according to records of internal memos between local, state and federal agencies.

“I had never seen more blatant racism that basically [said], ‘You don’t deserve clean water. You don’t deserve to be healthy, and therefore, we are not going to act,'” Bullard says.

What is environmental justice?

According to the EPA, environmental justice is defined as “fair treatment and meaningful involvement of all people, regardless of race, color, national origin or income” with respect to environmental laws. While protection from hazards is key in this concept, so is having a proverbial place at the table, with access to the decision-making process.

Bullard knows firsthand that this can seem like a David and Goliath–like fight. He fought alongside the Holt family for eight years, working with them on their environmental and civil rights lawsuits, which ultimately ended in settlements with the county, city and state. But justice didn’t end there. Since the wells were still contaminated and would be for years, the city connected about 40 homes to a public water supply for free.

They may have won a settlement, but in the meantime the family lost the father, Harry Holt, to cancer. His widow, Sheila Holt, has breast cancer; her mother also has cancer.

How can we support environmental justice?

Be vigilant

If you see something, say something. “You could call the Environmental Protection Agency’s enforcement hotline if you see illegal dumping or flaring that’s happening illegally from a plant,” advises Ali. You can also reach out to your local health department about anything that seems not right or an injustice. A Google search will also turn up a number of environmental justice networks that are ready to help educate or assist the public. Consider getting familiar with some of the key players in the environmental justice space, from the EPA and the CDC to the Department of Health and Human Services.

Make leaders listen

It’s important to vote for candidates who prioritize the well-being of all citizens—and then hold them accountable. “Whether they’re Democrat, Republican or independent,” says Ali, “we should be asking the really tough questions, like, ‘What does your platform look like in relation to environmental justice? What are your sets of ideas about how we help to strengthen communities? How do we help communities move from surviving to thriving?'”

Volunteer and donate

As with other big issues like gun law reform and abortion laws, getting the word out and lobbying for change on a grassroots level can make a big impact. In Cancer Alley, for instance, environmental justice groups sued the government for allowing yet another plastics company to create a plant in the area, while other groups, like ones in Michigan, are pushing for their states to adopt Equal Rights Amendments, environmental justice legislation and climate justice legislation.

In addition to local groups, there are also nationwide groups you can check out:

And, of course, money always helps any cause, so consider donating as well.

Know your community’s risks

“In order to get solutions, you must have the data,” says Bullard. He urges citizens to plug their zip codes into EJScreen, a mapping tool created by the EPA, to show the general public what environmental health hazards are present in their neighborhoods. “You can have neighboring ZIP codes and life expectancies with a disparity of 10 to 15 years,” he notes.

Take action

If you’re alarmed by your report, contact your local, state and federal officials to push for change. Start a petition, or get loud and stage a protest.

Meaningful change may take time, but Bullard encourages the public to remember the grit and spirit of a late, great civil rights activist. “Like John Lewis said, ‘You get in good trouble.’ And others can benefit.”

Sources:

- Robert Bullard, PhD, environmental justice expert and author

- Science Advances: “PM2.5 polluters disproportionately and systemically affect people of color in the United States”

- Washington Post: “‘This is environmental racism”

- Clean Air Task Force: “Fumes Across the Fence-Line”

- JAMA Network: “Association of Air Pollution and Heat Exposure With Preterm Birth, Low Birth Weight, and Stillbirth in the US: A Systematic Review”

- Mustafa Santiago Ali, vice president at the National Wildlife Federation and a 25-year veteran of the Environmental Protection Agency

- IOP Science: “Air pollution is linked to higher cancer rates among black or impoverished communities in Louisiana”

- United Nations: “Environmental racism in Louisiana’s ‘Cancer Alley’, must end, say UN human rights experts”

- American Bar Association: “Human Rights, Environmental Justice, and Climate Change: Flint, Michigan”

- ABC 12 News: “Flint marks eight years since start of the water crisis”