Ibram X. Kendi on His New Book and Why Kids Today Need the Kinds of Books Being Banned

Updated: Mar. 14, 2024

The MacArthur Genius Grant winner on teaching children about anti-racism, fighting book bans and introducing young children to classic Black literature

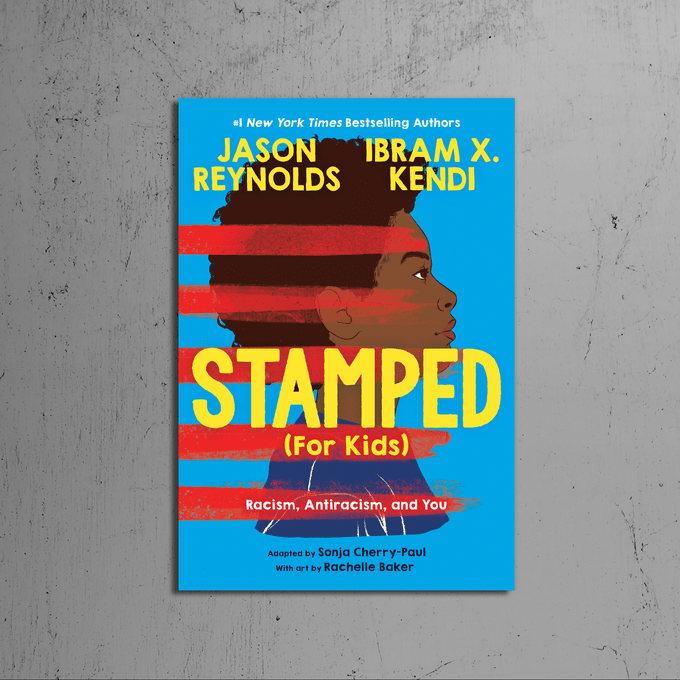

These days, Ibram X. Kendi is known as the bestselling author of books like How to be an Antiracist and Stamped: Racism, Antiracism and You, which he co-authored with young adult novelist Jason Reynolds. But when Kendi was growing up in Jamaica, New York, in the ’80s and ’90s, he says, he wasn’t much of a reader. The curriculum at his school focused largely on stories by and about white people, which was alienating to a young Black reader like Kendi. So when he found out that Stamped was one of the most-banned teen books of 2020, he took it personally.

“I know that there are young people right now who have not had the door to reading unlocked,” he told Reader’s Digest in a recent phone call. “That’s why it’s so devastating for me. Because I can imagine those kids today who need the types of books that are being banned.”

Book bans have risen sharply in the past few years. The number of banned books in 2020 was about 700, a figure that more than doubled to 1,500 in 2021, according to the American Library Association. Book banning rarely has to do with literary merit; some of the best books have been banned, including works by authors like Toni Morrison and J.D. Salinger. Books about racism and books by Black authors are prone to challenges and bans, making Kendi’s work especially vulnerable to censorship. LGBTQ+ books, feminist books and books by Latinx authors are also frequent targets.

The history we tell

With a title like Stamped: Racism, Antiracism and You, it’s not entirely surprising that Kendi’s book has been challenged. After all, a subset of parents is pushing for bans on critical race theory, and plenty of other books about racism have been challenged or banned outright. Even Holocaust books have been on the chopping block.

Critics like to claim that the reason they object to Kendi’s books is that “certain stories and history are left out,” a charge that he finds laughable. “As a historian, that’s a curious justification because you can’t pick up any history book and find that there were no stories that were left out,” he says. “There’s no history book that covers the entirety of human existence for all time.”

And as much of America learned when Juneteenth landed in the national spotlight, textbooks leave out a good deal of Black history.

Challenges also allege that Kendi’s work is “slanted” toward a particular view of race relations. “It’s so striking that when a book challenges notions of Black inferiority, it’s considered indoctrination,” he says. “But then when a book says nothing about Black people or reinforces notions of Black inferiority, it’s considered education.”

Anti-racism is for kids

Objections to Kendi’s work go beyond the history. Critics also charge it with being too heavy for children, who they say aren’t ready to learn about painful topics like racism and slavery. But he counters that it’s critical to teach kids how to think about and recognize racism when they’re young.

“It’s important for us as adults to be very deliberate in striving to be anti-racist and unlearning ideas that we have consumed over the course of our lifetime that would make us think that there’s something wrong or bad or worse about a particular racial group,” he says. “So, too, is it important for us to actively raise our children to recognize racial equality, to not connect skin color to bad or good behavior. And if we don’t do that as parents, then the world is going to teach them something different.”

That’s not just his take—it’s supported by research. “Scholars have documented consistently that if we are not educating our children to see racial equality the world will nurture them to see racial inequality,” he says.

But beyond that, he rejects the premise that adults shouldn’t have uncomfortable conversations with kids. And he thinks most people agree with him, whether they know it or not.

“As educators and parents and caregivers, we talk to our kids about stranger danger,” he says. “It’s a very uncomfortable conversation for our kids, but we’ve recognized that it’s protective for them to be uncomfortable so that one day they’re not hurt. We talk to our children about the importance of getting a shot because that shot is going to heal them, even though it’s going to make them uncomfortable for a little while. So there are a whole host of things that we do with the recognition that our kids are going to be uncomfortable. Because in the end, we know it’s going to make them healthy. It’s going to protect them, and it’s going to enrich our society. And to me, talking to them about racism should be one of those things.”

Anti-racism is for everyone

Kendi is adamant that diverse books are important both for Black kids who rarely see themselves reflected in the current canon and for people of all ages and races. Everyone loses out when we ban books, he argues.

“I think one of the beauties of the United States is that there are so many different people who have so many different experiences of so many different identities and have so many different worldviews,” he says. “And the beauty about literature is when it can provide a range of diversity, of worldviews, of experiences, of identities, so that readers can find themselves in books.”

These diverse stories don’t just help us better understand ourselves, though. They also help us understand and empathize with people of different backgrounds.

“It is a huge loss for people to not be able to find themselves in books, particularly if they’re a person of color, if they’re queer, if they’re women or trans,” Kendi says. “And it’s a huge loss for people who are not trans and people who are not queer and who are not people of color. It’s a loss because they’re not able to learn about others.”

The stories we share

Kendi’s next project is something of a departure from his usual practice of writing books about race relations. Magnolia Flower is a picture book with text adapted from Zora Neale Hurston’s short story of the same name and illustrations by Loveis Wise.

But it also fits in perfectly with his mission to get kids thinking and learning about race—and reading books by Black authors—as young as possible. Hurston is, after all, one of the preeminent Black authors of the 20th century, and her classic novel Their Eyes Were Watching God is taught in high school classrooms across the country. (Parents challenged it in the late ’90s because of “sexual explicitness and language.”)

“During the pandemic, my daughter was home from school, like many other people’s children in 2020, so of course, I was reading her picture books. And at the same time, I was reading some work from Zora Neale Hurston, and it came to me that it would be beautiful to be able to adapt one of her short stories or even some of the folklore she collected for children,” he says. “I thought about how my daughter has to wait till she gets much older in order to be exposed to Zora. And I just had this overwhelming desire to ensure that our young people can learn about and read about Zora Neale Hurston, even at 4 years old.”

Magnolia Flower centers on a family that lives in a Maroon, a secret village where Black and Native people could live freely during years of slavery and displacement. It allows children of color to see themselves on the page, to start learning about their histories and to know that there is a rich history of Black artists and intellectuals in this country whose ranks they might one day join.

The fight is everyone’s

Kendi doesn’t expect Magnolia Flower to face the same challenges that books like Stamped have, but he still encourages everyone to get active and join librarians fighting book bans to prevent more bans from being instituted.

“Often, book banning is at a very local level,” he explains. “So whether it’s the local school district or the local library system, I think it’s important for everyone to think about how they can contribute to stopping people from banning books, whether that’s through creating an organization that will advocate in your local community, whether that’s running for school board, whether that is organizing parents in a particular school. We have to think about ways in which we’re going to be organizing and we’re going to be putting ourselves in positions of power to ensure that books are not banned. Anyone can do that. Anyone can join an organization, they can fund an organization, they can volunteer for an organization.”

He’s also energized by the response he’s seen from teens forming online book clubs and banned book clubs to push back against censorship. “One of the most exciting reactions to all these book bans is witnessing young people reading Stamped or Antiracist Baby. That’s what really brings me joy. Anyone who knows young people knows that if you stop them from doing something, they’re going to find a way to do it anyway.”

Read books by Ibram X. Kendi

Sources:

- Ibram X. Kendi, author and founding director of the Boston University Center for Antiracist Research

- American Library Association: “National Library Week kicks off with State of America’s Libraries Report, annual ‘Top 10 Most Challenged Books’ list and a new campaign to fight book bans”

- American Library Association: “Top 10 Most Challenged Books Lists”