Justin Barber and the Two Million Reasons for Murder

Updated: Feb. 14, 2023

Justin Barber said his wife was killed during a late-night robbery—but the details didn't add up. Seek the truth in this harrowing true crime story.

For couples craving solitude, the beach at Guana River State Park is an ideal spot for a late-night tryst. Hidden by thickets of saw palmetto, the ribbon of sand unspools along a lonesome stretch of Route A1A south of Jacksonville, Florida. Entry after sunset is officially forbidden, but intrepid lovers often park on the roadside and follow wooden walkways into the dunes.

For couples craving solitude, the beach at Guana River State Park is an ideal spot for a late-night tryst. Hidden by thickets of saw palmetto, the ribbon of sand unspools along a lonesome stretch of Route A1A south of Jacksonville, Florida. Entry after sunset is officially forbidden, but intrepid lovers often park on the roadside and follow wooden walkways into the dunes.

Justin Barber, 30, and his wife, April, 27, had done just that on August 17, 2002. They were tipsy and amorous, Justin later recalled, having celebrated their third wedding anniversary with dinner at an Italian restaurant, followed by drinks at a bar. Around 10:30 p.m., as they strolled along the water’s edge, a tall man in a baggy T-shirt approached them. He waved a pistol and yelled something about cash and car keys. Justin stepped in front of April. The gun went off. He grappled with the stranger. The beach went black.

When Justin came to, he found he’d been shot four times—in both shoulders, under the right nipple, and through the left hand. The man was gone. Justin called April’s name, then spotted her floating face down in the surf. There was a .22-caliber hole in her left cheek. He dragged her up the beach until his strength gave out, then left her and staggered to the road to flag down passing cars. When none stopped, he climbed into his Toyota 4Runner, turned on the flashers, and gunned it. Nearly ten miles down the road, a motorist signaled him to pull over and called 911. As Justin was transferred to a hospital, police and rescuers searched the beach for April.

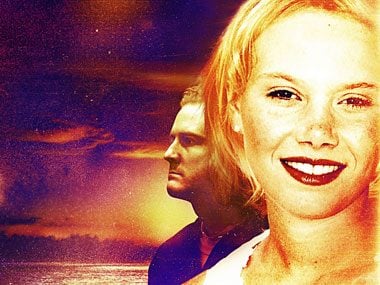

Lt. Ben Tanner of the St. Johns County Sheriff’s Department found her. “She was lying with her head to the north, facing the ocean,” he says. “She didn’t have a pulse.” April’s photo is etched into her tombstone; it shows a woman with a brilliant smile, corn silk hair, and exquisite cheekbones. But her beauty wasn’t just skin-deep. April was a survivor of family tragedy who poured her energy into helping others, from her younger siblings to the cancer patients she served as a radiation therapist. “She put more value on relationships than most people do,” says her best friend, Amber Mitchell, an Internet entrepreneur in Oklahoma City. “She didn’t take life for granted.”

April’s photo is etched into her tombstone; it shows a woman with a brilliant smile, corn silk hair, and exquisite cheekbones. But her beauty wasn’t just skin-deep. April was a survivor of family tragedy who poured her energy into helping others, from her younger siblings to the cancer patients she served as a radiation therapist. “She put more value on relationships than most people do,” says her best friend, Amber Mitchell, an Internet entrepreneur in Oklahoma City. “She didn’t take life for granted.”

Who would want to snuff out such a vibrant spirit? Justin would tell investigators that he thought the culprit was a crazed mugger. But a few of those close to April suspected the killer was someone she knew very well.

April grew up in Hennessey (pop. 2,024), Oklahoma, an island of century-old storefronts and modest homes in a sea of prairie. She was an A student, thoughtful yet popular, as comfortable at a rodeo as in biology lab.

During April’s senior year of high school, her mother was diagnosed with lung cancer and died after six months of agony. April’s father, an oil field worker, was too traumatized to care for the kids. Though relatives took them in, April became a surrogate mom to her siblings Julie, then nine, and Kendon, one. Still, she kept her grades up. She went on to the premed program at Oklahoma State University, then studied radiation therapy at the University of Oklahoma.

In October 1998, Amber Mitchell introduced April to one of her business school classmates—a handsome blond named Justin. The two clicked instantly. April had dated a string of men for whom fidelity was not a strong point; Justin seemed different. He spoke of his Christian values. He had grown up in a town even smaller than Hennessey, herding cattle with his brother on their parents’ 120-acre spread. A quiet, solitary boy, he’d blossomed into a star athlete in high school and graduated as valedictorian. He’d married in college and spent a few years drifting between jobs, but when he met April, he was newly divorced and aflame with ambition. “He was among the best and brightest in our class,” says Amber. “April was attracted to his drivenness.”

April and Justin quickly became engaged. On August 4, 1999, they married in a small ceremony in the Bahamas, then relocated for Justin’s new job in Douglas, Georgia. April found work at a hospital. A month later, her siblings moved in, and the trouble began. Julie was 15 then, and her rebellious behavior infuriated Justin, sparking fights between April and him. At one point, according to several of April’s confidants, he threatened to never let April bear his children. Within a year, Julie and Kendon were back in Oklahoma.

By then, some of April’s loved ones had begun to see a disturbing pattern. “Justin seemed very into appearances,” says April’s aunt Patti Parrish, a civil court judge. He tried on his jeans from high school every month and fasted until they fit. He made fun of his overweight mother behind her back and publicly criticized April’s singing voice, her clothing, and her weight. He warned her not to embarrass him at his company Christmas party and discouraged her from contacting him at work. When his barbs made her cry, he mimicked her sobs. Yet April tolerated Justin’s mistreatment.

But in January 2001, when Justin was transferred to Jacksonville, April decided to stay put. “She told me that if they lived together every day, they’d kill each other,” Amber says. Justin bought a condo in an upscale neighborhood, and the two saw each other on weekends. Usually it was April who drove the three hours to visit.

She just wasn’t ready to give up on Justin. He could be charming, and his criticisms dovetailed with some of her deep insecurities. “She was harder on herself than anyone else,” says Amber. “She put up with a lot from her men.”

Still, there was always a point at which she drew the line.

The man in the hospital bed was personable and seemed eager to help catch his wife’s killer. But something about him made Detective Howard “Skip” Cole uneasy. “His body language and demeanor didn’t seem appropriate,” says Cole, 35, who’d been assigned to lead the investigation.

In the days that followed, Cole’s suspicions grew. Justin’s story was frustratingly vague, and the details kept changing. The case raised a slew of questions. How did Justin escape with minor wounds, while his wife was killed with a single shot? Why did he claim she’d been drinking, when her blood-alcohol level measured .000? Why had he left his cell phone at home that night, and why didn’t he use April’s? What made him drive so far in search of help, when there were mansions and gas stations along his route?

Meanwhile, April’s Aunt Patti remembered that in the summer of 2001, April had told her Justin wanted them to take out $2 million insurance policies on each other’s lives. “She asked if I didn’t think it weird,” Patti says. “I told her yeah but said I didn’t think they would qualify. She called back the next day and said, ‘You can’t say anything to Justin. He’ll be furious if he finds out I told you.’”

Justin found a company that would cover them. Not long afterward, April began to suspect he was having an affair. She told Amber she’d found an earring in his bedroom, and in July 2002, she discovered he was playing tennis regularly with a rental-car agent named Shannon Kennedy. April e-mailed him at work, asking him to tell her when he was socializing with other women. Justin responded with a sarcastic message listing every female he’d glimpsed that day.

April told her boss, Ramesh Nair, that she was going to confront Justin on their anniversary—August 4. She visited Justin that weekend; when she returned, she told Nair that she’d threatened to end the marriage. On Friday the 16th, she drove back to Jacksonville. The next night, she was dead.

Amber and Patti’s first thought was, Justin did it. And Nair was struck by a memory from a few months earlier: “One day, out of the blue, April said, ‘If anything happens to me, suspect foul play.’ I answered with a joke, and she looked hurt, like, You’re not taking me seriously. Don’t forget.”

Justin asked Patti if she would front for April’s burial expenses. “What about the $2 million?” she responded. Startled, he said, “Did April tell you?” He told her he thought the policy had lapsed. Patti did some digging and learned that it hadn’t.

At the funeral, in Hennessey’s First Baptist Church, a crowd of 300 overflowed the pews. Several attendees were struck by Justin’s failure to cry, though he appeared to be trying. The next day, Patti called Detective Cole. She told him what she knew and put him in touch with Amber.

During a search of Justin’s condo, Cole found the insurance policy. Brought in for questioning, Justin denied his affair with Shannon Kennedy until he was told she was in the next room; then he insisted that his marriage had been generally placid.

Cole knew he was dealing with a liar, but arresting Justin for murder was another matter. There were no witnesses; no weapon had been found. Even the motive remained fuzzy. Justin had a base salary in the $70,000s; his wife earned nearly as much. Living apart from her, he could cheat with relative impunity. Did he kill her—and shoot himself—simply to upgrade his lifestyle a few notches?

Cole and his team probed the couple’s financial records and Justin’s computer files. They analyzed bloodstains, ballistics, and the abrasions on April’s body. By July 2004, they had enough evidence to take Justin into custody, but it took another two years of spadework—and advancements in computer forensics—before they were ready to go to trial.

The proceedings began on June 12, 2006, in a courthouse in St. Augustine, Florida. Much of what the sleuths had dug up was inadmissible: April’s conversations with Nair, for example, and Justin’s purchase of a bulletproof chest plate before the killing. Instead, the case turned on a few stark facts.

First, there were the trysts: Justin, it emerged, had carried on at least five during his three-year marriage. Shortly before the killing, he asked Shannon Kennedy to travel with him to California; two days afterward, he stopped by her office and demanded to see her. He pursued her for several more weeks before transferring to Portland, Oregon.

Then there was money: Justin had $58,000 in credit card debt. “The adage is true, even if it’s corny,” Assistant District Attorney Matt Foxman told the jury. “The defendant has two million reasons to commit this crime.”

That took care of motive. As to method, prosecutors argued that Justin had spent a year planning the crime. The most damning evidence came from his laptop. On February 9, 2002, Justin Googled “medical trauma right chest.” On Valentine’s Day, he tried “gunshot wound right chest.” The prosecutor asked, “What are the odds of somebody researching ‘gunshot wound to the right chest’ and getting a gunshot wound to the right chest six months later?”

On July 19, Justin Googled “Florida divorce” and doubtless discovered that if April dumped him, he could no longer be her beneficiary. And on August 17, an hour before the fatal outing, he downloaded the Guns N’ Roses song “Used to Love Her (But I Had to Kill Her).” Foxman played the track in court. Justin, he said, had been psyching himself up for murder.

Finally, there was the crime-scene evidence. Justin claimed he hauled April from the water after she was shot, carrying her in at least nine different positions. Yet the blood on her face all flowed in one direction, suggesting she had been shot on the walkway and left there to die. Foam at her nose and mouth indicated that she’d suffered a “near-drowning episode” before the shooting.

Foxman laid out his theory: Justin intended to shoot April, load her corpse in the car, and drive off in search of “help.” The scheme went awry when she tried to run. He held her underwater until she stopped struggling, then dragged her to the walkway, where he shot her and himself. The plan derailed again when his pain kept him from carrying her farther. Justin had to modify his tactics, Foxman said, but his strategy never changed: “He wanted the $2 million, he wanted sympathy for being shot, and he wanted to look like a hero who’d tried to save his wife. He wanted it all.”

Justin’s attorney, Robert Willis, gamely offered alternative interpretations for each scrap of evidence. But Justin’s behavior in a different courtroom three years earlier may ultimately have swayed the jury.

Midway through the first-degree premeditated murder trial, prosecutors played a video deposition Justin gave in 2003 as part of a civil case concerning insurance proceeds. On the tape, the plaintiffs’ attorney grills Justin on the attack, his affairs, his sex life with April. He claims not to remember some key details but answers even the most disturbing questions with uncanny calm. His mouth is set in a downward curve, and he dabs his eyes once. Otherwise, he shows little emotion. When the lawyer asks him to recall the high points of his marriage, Justin says tersely, “We were in love.” Pressed for details, he says, “I don’t recall specifically.”

He seemed equally unmoved when the jurors of the criminal trial, after 33 hours of deliberation, announced their verdict: guilty. His supporters wept, as did April’s mourners. Justin barely blinked, even when the jury recommended the death penalty a week later. (Judge Edward Hedstrom later sentenced him to life without parole.) Such detachment is a classic symptom of sociopathy, says University of Texas psychologist Shari Julian, an expert on the disorder.

“The true mark of a sociopath is that he always wears a mask,” Julian says. They tend to be intelligent, charismatic, and monstrously manipulative.

“He’s a very gentle person,” says Justin’s mother, Linda, who still believes in his innocence. “A good guy.”

But Amber Mitchell rejoices that the mask is off at last. “This has been a long, horrible chapter in our lives,” she says. “I want the jury to know they got it right.”