This Is Why the U.S. Constitution Uses F’s for S’s

Updated: Oct. 24, 2022

Don't worry—our Founding Fathers did know how to spell.

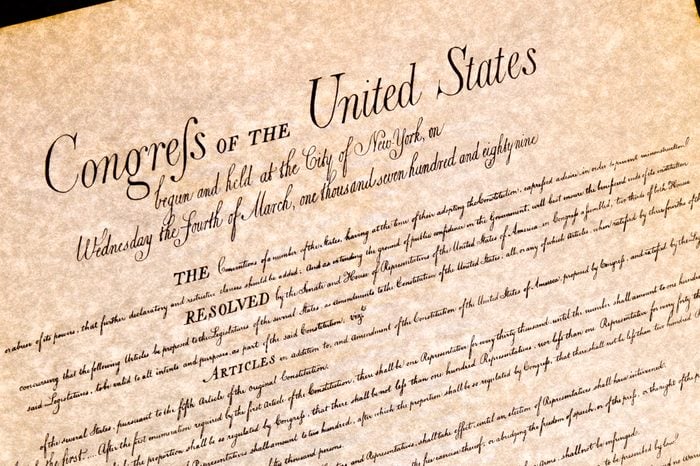

If you look closely at an old document like the U.S. Constitution, you’ll notice an odd quirk in the spelling: Most of the time, the writers put an F where an S should be. It wasn’t because the writers didn’t know how to spell; it all comes down to an outdated grammar rule.

Let’s get one thing out of the way: That F-like letter is not an actual F. It’s called a long S (ſ). Unlike a lowercase F, the horizontal line doesn’t strike all the way through but only goes on the left side. In some cases, like the glaring example of “Congreſs” in the Bill of Rights, there’s no bar at all.

The long S was pronounced just like a normal (short) S, and its history dates back to the first century when Romans used an early form of it when writing quickly in cursive. When a standardized script was developed for Europe in the eighth century, the ſ/S distinction stayed intact. Did you know about these glaring grammar mistakes in the U.S. Constitution?

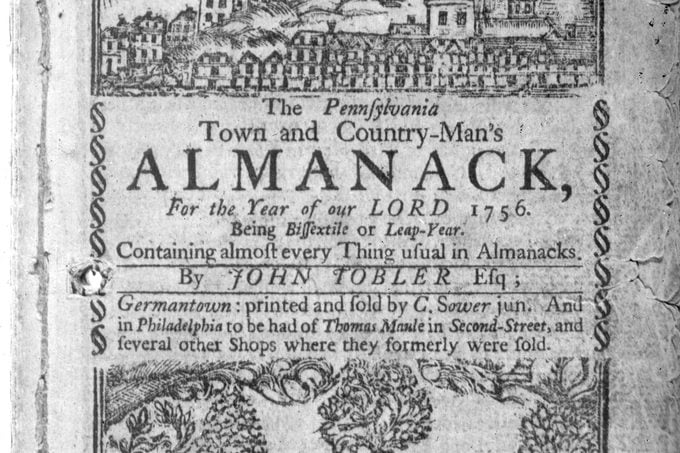

The rules about when to use the long S vs. short S changed over time and depended on the writer’s style. By the 17th and 18th centuries, the long S was still being used, but there didn’t seem to be clear rules about when to use it. In general, it would go at the beginning and middle of a word, but there were some exceptions. If a long S was capitalized, it would look how we’d expect: S. Some writers would use ſ once in a double-S word (e.g. Congreſs), but others would use it both times (e.g. biſſextile). Often, a short S would go next to the letter F (e.g. misfortune) to avoid confusion.

Around 1780, the long S suddenly fell out of fashion. It’s thought that as technology advanced, printers wanted to simplify their typesets and kept just one form of S in their kits. That ſure ſounds fine to us. Next, learn about the U.S. Constitution myths that most Americans believe.

Sources:

- Medieval Calligraphy: Its History and Technique

- TUGboat, Volume 32 (2011), No. 1: “The Rules for Long S”

- Lexico: “Why Is The Letter “F” Used Instead of “S” In Old-Fashioned Spellings?”

- Historyofinformation.com: “The Gradual Disappearance of the Long S in Typography”