My Father and I Weren’t Close When He Died, but Eating Fast Food Brings Back Good Memories of Him

Updated: Jun. 08, 2021

In his short, difficult life, a greasy meal and a soda were a balm for my father. Every time I eat a chicken nugget, I feel close to him once again.

It’s autumn again, the eighth since my father died, and I’m craving chicken nuggets.

My father would have understood. I don’t remember him saying “I love you,” which isn’t a common phrase in Mandarin, his preferred language. We always had a bit of a communication issue. But his love language was the simple pleasure of processed food.

I have a photo of the two of us, taken when I was two, at the gleaming flagship McDonald’s in Beijing. In the photo, I’m feeding my father a fry. We both beam.

My father was the fun parent, the indulgent one. He introduced me to fries, Cool Whip straight from the tub, and fizzy drinks. My father never reprimanded me for overindulgence as my mother did. He laughed. It didn’t seem to matter, then, that his English wasn’t fluent, or that my Mandarin was already slipping away.

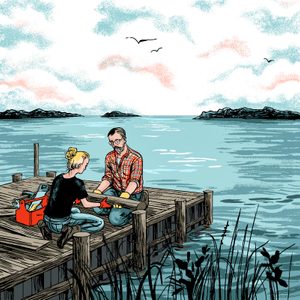

Our language of junk food evolved into one of secrets: a conspiratorial Happy Meal on our fishing trip alone, two liters of Coke guzzled together before my mother came home. I felt honored until I began to understand that my father kept secrets from me too.

In third grade, I came home newly evangelized to the dangers of cigarettes and threw away my father’s packs. He raged, then promised to quit, but I kept smelling smoke in his clothes and car.

My father was not virtuous. He was a man of vices and quick pleasures: processed foods, nicotine, gambling, adultery. I didn’t ask why he turned to these—that wasn’t how our family operated, and anyhow, language remained a barrier.

Instead, I distanced myself. I knew the person I aimed to be, and that person was not reflected in my gambling-addicted, divorced, blue-collar father. He had become a shameful artifact, one I wanted to leave behind. I focused on my own life with the impersonal callousness of youth.

My father died two years after I graduated from college. He was 49. I was 22. I grieved his passing, and then I grieved the fact that I never fully knew him. There were questions I had never thought to ask and nuances I hadn’t been able to articulate in my language or in his.

I used to blame my father for the weakened body that killed him—a product, I thought, of his weakened virtue. But the older I get, the more I see myself compromising too.

And so, each autumn, I think: Now I’m the age at which my father followed his spouse to a country where he didn’t speak the language; now I’m at the age at which he was fired from his job and took a minimum-wage gig; now I’m at the age at which he found his first online gambling website, as irresistible to him as the dumb games on my phone are to me.

And at each intersection, I think: The age I am is far too young for the responsibilities he bore. How can I resent my father for being the product of such a staggeringly unfair world?

I can imagine the giddy power my father must have felt upon moving to America to discover that McDonald’s was now the stuff of everyday. It was cheaper than fish, more accessible than fresh fruit, and simpler than a long-distance phone call to Beijing in which he felt compelled to hide his difficulties, his loneliness and alienation.

And I can imagine, too, the balm of preternaturally smooth processed meat to a tongue made clumsy by translation; how sugar might soothe an ego bruised by rejection, racism, and the need to ask whether a store accepts food stamps. Under such conditions, the demand for perfect virtue feels impossible, even cruel. I can imagine how it might be easier to hand your child a golden nugget—how the gesture is a promise of abundance and pleasure, however short-lived.

There are vices we must allow ourselves, even if they theoretically shorten our lives by a day or a week or a year—because first we have to get through this day, this week, this year.

Is it wrong to compare my father to a processed piece of deep-fried food? Because I think of him whenever I bite into one. It’s a more faithful representation than the usual metaphors of fathers as safe harbors, rocks, or teachers. None of those rings true when it comes to my father.

The next time the urge strikes, I’ll have a nugget or two or four. There will be the rush of additives, the hit of engineered pleasure. And in that moment, in a communion across a golden crust, I will understand my father completely.