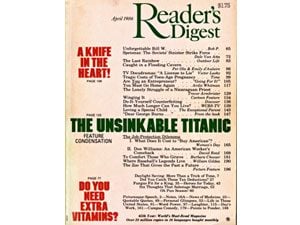

The Unsinkable Titanic

Updated: May 09, 2023

To commemorate the 100th anniversary of the sinking of the Titanic on April 15, 1912, we dug into our archives for this remarkable account of the disaster and its aftermath. Plus: Titanic video clips of the survivors, the wreckage, and more.

For its original publication in 1986, our editors had compiled and condensed this story from dozens of sources. Today, the chronicle is as fresh and moving—and shocking—as it was several decades ago.

For its original publication in 1986, our editors had compiled and condensed this story from dozens of sources. Today, the chronicle is as fresh and moving—and shocking—as it was several decades ago.

Plus: 13 Things You Didn’t Know About the Titanic >>

The White Star Liner Titanic, the largest ship the world had ever known, sailed from Southampton, England, on her maiden voyage to New York City on Wednesday, April 10, 1912. She was built with double bottoms, and her hull was divided into 16 watertight compartments. She was thought to be unsinkable. The liner carried more than 2,200. Occupying the first-class suites were many well-known men and women—Col. John Jacob Astor and his young bride; President William Howard Taft’s close adviser Maj. Archibald W. Butt; former congressman and Macy’s chief executive Isidor Straus; and J. Bruce Ismay, managing director of the White Star Line. In the crowded cabins of steerage class were more than 700 immigrants heading to the land of promise.

Sunday the 14th dawned fair and clear. At 9 a.m., a message from the steamer Carolina sputtered into the wireless shack: “Captain, Titanic—westbound steamers report bergs, growlers, and field ice in 42 degrees N. from 49 degrees to 51 degrees W. Compliments—Barr.” The message was delivered to Capt. E. J. Smith, who wired an acknowledgment.

Just before noon, the rasping spark of early wireless spoke again across the water. It was the Baltic, warning the Titanic of ice on the steamer track. The wireless operator sent the message up to the bridge. Captain Smith read it as he was walking on the promenade deck and then handed it to Bruce Ismay without comment. Ismay read it, stuffed it into his pocket, told two women about the icebergs, and resumed his walk.

It was bitter cold on deck that evening, but the night was calm and fine. After dinner, some of the second-class passengers gathered for hymn singing. It was almost 10 p.m. as the group sang the words of the mariner’s hymn: “Oh, hear us when we cry to thee, for those in peril on the sea.”

On the bridge was First Officer William Murdoch. At least seven wireless warnings about ice had reached the ship; lookouts had been cautioned to be alert. At 22 knots, its speed unslackened, the Titanic plowed on through the night.

High in the crow’s nest, lookout Frederick Fleet peered into a dazzling night. There was no moon, but the cloudless sky blazed with stars, and the Atlantic was like polished plate glass. Lookouts were not supplied with binoculars, but at 11:40 p.m. Fleet’s eyes suddenly detected something directly ahead, even darker than the darkness. At first it was small, but every second it grew larger and closer. Fleet quickly banged the crow’s nest bell three times, the warning of the danger ahead. At the same time, he lifted the phone and rang the bridge.

“What did you see?” asked a calm voice at the other end.

“Iceberg right ahead,” replied Fleet.

“Thank you,” acknowledged the voice. Nothing more was said.

On the bridge, Quartermaster Robert Hichens was at the wheel. First Officer Murdoch gave the order: “Hard astarboard!” This meant turning the stern of the ship to starboard and the bow to port. As Murdoch telegraphed the engine room “full astern,” Hichens obeyed the spoken order and threw his full weight to the wheel.

In the crow’s nest, Fleet stood motionless as the silhouette loomed larger and larger. After what seemed an eternity, the Titanic’s bow finally swung to port and was beginning to clear the iceberg. Fleet braced himself as the forecastle brushed against the berg and ice tumbled onto the forewell deck.

At the very bottom of the ship, fireman Frederick Barrett had been hard at work stoking the furnaces in No. 6 boiler room. Foaming green seawater suddenly exploded through the Titanic’s side, about half a meter above the floor plates, shearing the starboard wall for the entire length of No. 6 and slightly into the coal bunker in No. 5. The alarm bell was jangling above the watertight door, which had just begun to descend. Barrett managed to leap through the doorway and into No. 5 boiler room as the door shut.

Meanwhile, in the first-class dining saloon far above Barrett, four members of the ship’s crew heard a faint grinding jolt that seemed to come from somewhere deep inside the ship. It was not much, but enough to rattle the silverware that was set for breakfast the next morning.

Passengers in their cabins felt the jar too. Maj. Arthur G. Peuchen, starting to undress for the night, thought it was like a heavy wave striking the ship. To Lady Duff Gordon, waking up from the jolt, it seemed “as though somebody had drawn a giant finger along the side of the ship.” Hearing that grinding jar in the first-class smoking room, Spencer V. Silverthorne rushed out onto the deck. With a few other passengers, he was in time to see the iceberg scraping along the starboard side, a little higher than the boat (topmost) deck. As it slid by, they watched chunks of ice breaking and tumbling off into the water. In another moment, it faded into the darkness astern.

The excitement soon disappeared. The Titanic seemed as solid as ever, and it was too cold to stay outside any longer. Slowly, every-one filed back inside.

As the grinding noise died away, Captain Smith rushed onto the bridge from his cabin next to the wheelhouse. There were a few quick words: “Mr. Murdoch, what was that?”

“An iceberg, sir. I hard-astarboarded and reversed the engines, but she was too close. I couldn’t do any more.”

In the stateroom of the Titanic’s principal designer, Thomas Andrews, the impact was so slight it escaped his notice. A knock on the door drew his attention. A sailor summoned him to the bridge, where the captain told Andrews what had happened. Water in the forepeak … No. 1 hold … No. 2 hold … mail room … boiler room No. 6 … boiler room No. 5. Water four meters above keel level in the first ten minutes, everywhere except boiler room No. 5. Put together, the facts showed a 300-foot gash, with the first five compartments hopelessly flooded.

The conclusion was inescapable. The Titanic was on her way to the ocean floor, some 13,000 feet below. Andrews estimated the ship had but 90 minutes left.

At 12:05 a.m.—about 25 minutes after that grinding jar—Captain Smith ordered Chief Officer H. F. Wilde to uncover the lifeboats. The Titanic carried only 16 boats and four canvas collapsibles capable altogether of holding about 1,180 of the 2,200 or so aboard. The captain himself then walked to the wireless shack. “Send the call for assistance,” he ordered.

“What call should I send?” Jack Phillips asked.

“The regulation international call for help. Just that.”

Less than 10 miles away, the Californian wireless operator Cyril F. Evans had closed down his set at the scheduled hour of 11:30.

The Light That Failed

The Cunard liner Carpathia, sailing from New York City, was bound for Gibraltar and the Mediterranean. Her extensive passenger accommodations—providentially—were nearly half empty.

The Carpathia’s radio operator was H. T. Cottam. Cottam’s heart nearly missed a beat when out of the night came the dread letters of the international distress call: “. Come at once. We have struck a berg. Position 41.46 N., 50.14 W. !”

Cottam raced up to the bridge and breathlessly informed the officer of the watch, who in turn went to the captain’s cabin.

Capt. Arthur H. Rostron later wrote: “So incredible seemed the news that, having at once given orders to turn the ship, I got hold of the Marconi operator. ‘Are you sure it is the Titanic?’ I asked him. ‘Quite certain,’ he replied. ‘All right,’ I said then. ‘Tell him we are coming.’ ”

“We are coming as quickly as possible,” Cottam telegraphed, “and expect to be there within four hours.”

“TU OM” (“Thank you, old man”).

After that, Cottam switched off his transmitter. He was careful not to do anything that might interfere with the Titanic’s signals. Presently, however, he overheard her exchanges with the Mount Temple, and other ships—though all this time the Californian, which now lay less than 16 kilometers distant from the sinking liner, remained silent.

Playing the Game

Aboard the Titanic, the passengers stood calmly on the boat deck—unworried but confused, waiting for the next orders. Each class kept to its own decks—first class in the center of the ship, second a little aft, third at the very stern or on the well deck near the bow. With uneasy amusement, they eyed how one another looked in life belts.

There had been no boat drill, the passengers had no boat assignments, and the going was slow. Second Officer Charles H. Lightoller, in charge of the port side, stood with one foot in Boat 6 and one on deck. He called for women and children. The response was anything but enthusiastic. Why trade the bright decks of the Titanic for a few dark hours in a rowboat? Even John Jacob Astor ridiculed the idea: “We are safer here than in that little boat.” When Constance Willard flatly refused to enter the boat, an exasperated officer finally said, “Don’t waste time—let her go if she won’t get in!”

There was music to lull them too. Bandmaster Wallace Henry Hartley had assembled his men, and the band was playing ragtime.

At 12:45 a.m., a blinding flash seared the night as the first rocket shot up from the starboard side of the bridge. There was no more joking or lingering. In fact, there was hardly time to say goodbye.

“It’s all right, little girl,” called Dan Marvin to his new bride. “You go and I’ll stay awhile.” He blew her a kiss as she entered the boat. “Be brave, no matter what happens,” Dr. W. T. Minahan told his wife as he stepped back with the other men. But Mrs. Isidor Straus refused to go. “I’ve always stayed with my husband; where you go, I go,” she said.

Watch a DiscoveryTV video about the sinking of the Titanic >>

Time was clearly running out. Soon the sea slopped over the Titanic’s forward well deck and rippled around the cranes, the hatches, and the foot of the mast. The nerve-racking rockets stopped, but the slant of the deck was steeper, and there was an ugly list to port.

A little group of millionaires stood quietly apart from the rest of the passengers on the boat deck; there were John Jacob Astor, George B. Widener, John B. Thayer, and a few others. Benjamin Guggenheim and his male secretary had changed back into evening dress. Declared Guggenheim, “We are prepared to go down like gentlemen.” He gave his steward—in case he survived—a message for his wife. “Tell her I played the game out straight and to the end. No woman shall be left aboard this ship because Ben Guggenheim was a coward.”

The poor Irish boys and girls from steerage were down on their knees, praying. An English priest, Father Thomas Byles, was moving to and fro among the passengers, hearing confessions and giving absolution. Every moment the black water was drawing nearer and nearer.

At 2:15 a.m., as the crewmen were tugging at the last two collapsible boats, the bridge dipped under, and the sea rolled aft along the boat deck. At this moment, the ragtime ended, and strains of the Episcopal hymn “Autumn” flowed across the deck and drifted into the still night far over the water.

God of mercy and compassion

Look with pity on my pain;

Hear a mournful, broken spirit

Prostrate at thy feet complain.

Hold me up in mighty waters …

“She’s Gone”

Second Officer Lightoller later wrote: “There was only one thing to do, and I [decided I] might just as well do it and get it over, so, turning to the fore part of the bridge, I took a header. Striking the water was like a thousand knives being driven into one’s body, and no wonder, for the temperature of the water was 28 degrees, or 4 below freezing.

“I suddenly found myself drawn to an air shaft by the sudden rush of the surface water now pouring down. I was held flat and firmly up against a grating on this opening with the full and clear knowledge that if this light wire carried away, there was a sheer drop of close on a hundred feet, right to the bottom of the ship. Although I struggled and kicked for all I was worth, it was impossible to get away, for as fast as I pushed myself off, I was irresistibly dragged back, every instant expecting the wire to go, and to find myself shot down into the bowels of the ship. I was still struggling and fighting when suddenly a terrific blast of hot air came up the shaft and blew me right away and up to the surface.”

Lightoller survived by joining some 30 others on an overturned collapsible boat before transferring to a lifeboat.

Passenger Lawrence Beesley described the great ship’s last moments as seen from Boat No. 7, 1.6 kilometers away: “We gazed awestruck as she tilted slowly up, revolving apparently about a center of gravity just astern of amidships, until she attained a vertically upright position; and there she remained—motionless!”

In the maelstrom of ropes, deck chairs, planking, and wildly swirling water, nobody knew what happened to most of the people. From the boats, they could be seen clinging like swarms of bees to deckhouses, winches, and ventilators. The famous and the unknown tumbled together in a writhing heap as the bow plunged deeper and the stern rose higher. Then a steady roar thundered across the water as everything movable broke loose—29 boilers … 15,000 bottles of ale and stout … 30 cases of golf clubs and tennis rackets … huge anchor chains … tons of coal … 30,000 fresh eggs … five grand pianos.

The structure supporting the first funnel collapsed. The mammoth smokestack seemed to lift off like a missile—its steel hawsers tearing the planking out of the decks—before it toppled on the people in the water.

The ship’s innards were now giving way. Crushed between the pressure of the sea and the gargantuan tonnage of the foundering liner, the celebrated watertight bulkheads crumpled with “big booms.” The Titanic’s stern steadily lifted, and suddenly her lights snapped off. They came on again with a searing flash and then went out forever.

Two minutes passed, the noise stopped, and the Titanic settled back slightly at the stern. Then slowly she began sliding under at a steep slant. As she glided down, the ship seemed to pick up speed. When the sea closed over the flagstaff on her stern, there was a gulp.

“She’s gone; that’s the last of her,” someone sighed to lookout Reginald Lee in Boat 13.

The starlight revealed a scene of utter horror. The sea all around was covered with a mass of tangled wreckage and the struggling forms of many hundreds of men, women, and children—slowly, inexorably freezing to death in ice-cold water. A sheet of thin, grey vapor hung like a pall a few meters above the surface.

Burial at Sea

Meanwhile, the Carpathia was making its way toward the Titanic. “Icebergs loomed up and fell astern,” wrote Carpathia’s Captain Rostron. “We never slackened, though sometimes we altered course to avoid them. As soon as there was a chance that we were in view, we started sending up rockets at intervals of about a quarter of an hour.

“There was no sign of the Titanic herself. By now—it was about 3:35 a.m.—we were almost up to the position. I saw a green light just ahead of us, low down. I knew that must be a boat. I brought the vessel alongside, and the passengers started climbing aboard. They were in the charge of an officer. I asked that he should come to me as soon as he was on board.”

Without preliminaries, Rostron burst out excitedly, “Where is the Titanic?”

“Gone!” replied Fourth Officer Joseph G. Boxhall. “She sank at 2:20 a.m.”

“Were many people left on board when she sank?”

“Hundreds! Perhaps a thousand or more!” Boxhall’s voice broke with emotion. “My God, sir, they’ve gone down with her!”

“Daylight was just setting in,” Rostron wrote, “and what a sight that new day revealed. Everywhere were icebergs. And amid the tragic splendor of them as they lay in the first shafts of the rising sun, boats of the lost ship floated.”

At 8:30, the last of the lifeboats and the collapsibles to arrive made fast and began to unload.

The Californian(which all night long had failed to react to the Titanic’s distress) had got under way at 6 a.m., steering for the position where she had earlier been informed the Titanic had sent out her distress call. Shortly after 8 a.m., steaming cautiously through the ice, she was near enough to the Carpathia for semaphore signaling. The Californian inquired what had happened; the reply came that the Titanic had foundered. Later the Californian received a wireless message from Captain Rostron: “I am taking the survivors to New York. Please stay in the vicinity and pick up any bodies.”

Before heading back, Rostron sent for the Reverend Anderson, an Episcopal clergyman aboard, and the people from the Titanic and Carpathia assembled in the main lounge to pay their respects to the dead. While they murmured their prayers, the Carpathia steamed slowly over the Titanic’s grave. There were few traces of the great ship. And at 8:50, Rostron felt sure there couldn’t possibly be another survivor. He rang “full speed ahead” and turned his ship for New York.

According to the captain of the Californian, no bodies could be found, and after an hour or so he resumed his voyage. There were in fact hundreds of corpses, drifting to and fro on the face of the waters. They may not have been seen because they were caught up in an immense ice mass moving in a northeasterly direction, and ships dared not venture near it. Later, those bodies were dispersed, possibly as a result of the ice breaking up in the Gulf Stream.

A week after the sinking, the cable ship MacKay-Bennett found 306 of them. When first sighted, they had seemed like a great flock of gulls on the water, bobbing gently in the swell. They were all floating in an upright position as if treading water, most of them in a great cluster surrounded by debris from the ship.

All day, crewmen worked at dragging the sodden bodies onto the deck. Those victims without identification were prepared for a proper burial at sea. By 8 p.m. that Sunday, the first burials began. MacKay-Bennett engineer Fred Hamilton kept a diary:

“The tolling of the bell summoned all hands to the forecastle, where 30 bodies are to be committed to the deep, each carefully weighted and sewed in canvas. The crescent moon is shedding a faint light on us as the ship lies wallowing in the great rollers. The funeral service is conducted by the Rev. Canon Hind; for nearly an hour the words ‘For as much as it hath pleased … we therefore commit his body to the deep’ are repeated, and at each interval comes, splash! as the weighted body plunges into the sea, there to sink to a depth of about two miles.

“Splash, splash, splash.”

Final Resting Place

“Like an enormous black freighter pointing at the sky,” as one survivor described her, the Titanic had heaved herself upright at 2:18 a.m. She hovered “in this amazing attitude” for moments—some said for several minutes—and took a sudden plunge forward as everything from dynamos to cabin furniture broke loose and fell toward the bow. Then she corkscrewed slightly to port; her submerged forecastle began to shudder, and the ocean surged into A and B decks. Before the Titanic’s lights went out for good, she appeared “like an enormous glowworm”—even the lamps in the underwater sections of the ship continued to burn, flooding the water around the bow with a green radiance.

Then she settled back to an angle of about 70 degrees and began slowly sliding into the sea. Muffled thunder sounded deep beneath the surface, and “she went down with an awful grating, like a boat running off a shingly beach.” She disappeared from view at 2:20 a.m. Within 15 seconds, the Titanic was 15 meters under the surface and accelerating.

There was desperate life, still, among the more than 1,000 souls remaining aboard. But only the few that somehow got to the surface had more than a moment’s hope. After another several seconds, the Titanic passed through the 30-meter level.

Somewhat deeper, there were implosions as the heavy steel bulkheads crumpled like tinfoil. The remaining buoyancy of the ship was sharply reduced. Her speed picked up to perhaps 20 knots.

A few minutes after total submersion, the inclination of the Titanic relented a bit from the steep angle at which she had slipped beneath the pond-smooth surface. Her giant boilers, which had crashed down through all the ship’s bulkheads and punched holes in the side of the bow, had gone on ahead, advance scouts seeking the ocean floor.

Leveled out in a flatter angle, the great ship now “kited” as it made its way through the icy depths, oscillating back and forth as she descended, somewhat in the manner of a leaf floating to earth.

Around 3,300 feet, she entered a zone never penetrated by sunlight. At that depth, where the ocean bears down at 1,615 pounds per square inch, no human life is possible. The stern, which had endured unimaginable stress when it rose toward the sky, had already pulled away. More cargo broke loose—cranes, the engine-room telegraph, chamber pots, serving platters, bottles of claret and champagne from the ship’s wine cellar near the stern. Then, at about 8,000 feet, the Titanic thrust her bow into the benthic current, a vast, subsurface, slow-moving river.

The ship had been sinking for seven minutes now, and the ocean floor was still several thousand feet below. She entered a hilly landscape of river valleys, tributary streams, and outcroppings.

Her stern had been floating free of the forward section and had partially disintegrated, scattering derricks, propellers, and even personal effects from the crew’s quarters. Bursting open, too, were the individual refrigerators, aft on G Deck, to disgorge their contents: fish, vegetables, ice cream, beef, poultry, cheese, fruit, and flowers.

Finally the Titanic slammed down. It will never be known which of the two sections, bow or stern, hit the brownish seafloor first. They kicked up huge clouds of sediment, which mingled with great clods of the ship’s boiler coal. The bow section came to rest on its keel, with only a slight list to port. The stern, some 300 meters away, disintegrated further upon impact. Unseen, the sediment drifted down as a ghostly snow.

Now the fractured hulk would be a permanent tomb for the mighty and the lowly; for the ship’s captain and most of his crew, for musicians, clergymen, and millionaires, and for teachers, bricklayers, carpenters, nurses, farmers, dishwashers. There, at about 13,000 feet, people from some 20 nations lay in 37° F. water under pressure of 6,365 pounds per square inch.

The time was close to 2:30 a.m., Monday, April 15, 1912. The Titanic’s maiden voyage had lasted four days, 17 hours, and 30 minutes.

The Search Begins

Parallel investigations, the first by the U.S. Senate, the second by the British Board of Trade, probed into the tragedy of the Titanic. Both agreed that the great ship had ignored repeated warnings and steamed at full speed through a sea of deadly ice. There was a “ram-you-damn-you” philosophy in those days among all the steamship lines. They wanted to deliver “express train” service, holding exactly to schedule even if it meant going full tilt through fog banks, ice fields, or fleets of fishing vessels. The Titanic paid the price for this folly.

After the investigations were ended, save for an occasional memoir, little was added to the tragic account of the . Yet the story still stirred in the psyche of the world. To this day, invoking the name of the Titanic has an emotional value greater than all but a handful of history’s most extraordinary events.

Then, in 1963, the first of a series of deepwater disasters fostered the development of equipment and techniques that would finally make it possible to find the Titanic.

The first was that of the nuclear submarine USS Thresher, which sank 220 miles off Cape Cod on the morning of April 10, 1963. Atlantis II, a research vessel from the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution, attempted to take pictures of Thresher. A 500-pound camera with strobe lights was lowered 8,000 feet over “protuberances” located by the U.S. Navy. It was, said Woods Hole’s former head of geophysics, J. B. Hersey, like dropping “a Ping-Pong ball into a beer can from the top of the Empire State Building while blindfolded and during a northeaster.”

Nevertheless, photos were obtained showing crumpled sheet metal, torn lengths of electrical cable, even an open book. The Navy’s deep-diving bathyscaphe Trieste later dived to the ocean bottom and, using a device similar to a mechanical arm, retrieved identifiable debris from Thresher.

Five years later, a Russian Golf II-class submarine sank northwest of Hawaii. It was located through the use of sensitive detection equipment—hydrophones, sophisticated cameras, side-scan sonar, magnetometers. A high-security U.S. government-sponsored project later developed retrieval techniques, including a clawlike device called Clementine on the end of a five-kilometer-long “pipestring” that was used to bring part of the sub to the surface.

One scientist interested in finding the Titanic was Robert D. Ballard, a marine geologist at Woods Hole. In 1971, Ballard proposed using Alcoa’s Seaprobe—a camera sled lowered on lengths of drill pipe—to locate and photograph the wreck. Ballard would then descend in the submersible Alvin, which was certified to go to the ’s depth. But no financial backing could be found for the proposal. Then, in 1980, a Texas oilman geologist, Jack Grimm, announced he would finance an expedition.

At Columbia University’s Lamont-Doherty Geological Observatory, William Ryan, an oceanographer, read in the newspaper about Grimm’s project and was intrigued by its scientific possibilities. He offered Grimm help and proposed using deep-tow, side-scan sonar to find the ship. He also suggested that the man who pioneered its development for deep-ocean surveying, Fred Spiess of Scripps Institution of Oceanography in La Jolla, California, could be of great help. Grimm accepted Ryan’s offer.

It would not be easy. The Titanic’s resting place, Ryan said, “is in one of the largest known areas of natural magnetic disturbance in the North Atlantic.” The Titanic sank near what is now known as the J-Anomaly Ridge, a 110-million-year-old volcanic feature of high magnetism.

Between July 31 and August 16, 1980, some 500 square miles of North Atlantic ocean bottom were mapped by Grimm’s chartered vessel, H. J. W. Fay, and its long-range, side-scan sonar. At least three good acoustic targets were detected that matched the size of the Titanic, but fate dealt a severe blow to the expedition when a storm came up and tore off the vital magnetometer. Spiess jury-rigged another one out of a shampoo bottle and some wire from a discarded exciter belonging to the ship’s generator. But the weather got worse, supplies and fuel ran low, and the Fay headed into Boston.

Grimm confidently promised that a 1981 expedition would return with photographs of the sunken wreck. The searchers did obtain a photo of a propellerlike object, but it could not be positively identified. And a 1983 expedition was compelled by gale-force winds to abandon the mission.

Despite these failures, Robert Ballard remained optimistic. “I always thought that finding the Titanic was not the hardest part of the puzzle,” he said. “Filming it in an appealing way would be the hardest part.”

The violent gales of the North Atlantic soon put his confidence to the test.

Mud or Bones?

In Robert Ballard, there is something of the astronaut, Jules Verne, and Lewis and Clark wrapped into one. Tall and athletic, already well-known as a skilled diver and deep-sea explorer, he “watched from the sidelines” with mixed emotions as the Grimm expeditions continued. “Their effects convinced me that the key to discovering the Titanic lay in having sufficient time on target to conduct a thorough search of an area of 100 to 150 square miles.”

Thus Ballard turned to “an old friend—France,” in order to gain more time at sea searching for the elusive wreck. He was soon to join forces with Jean Jarry and Jean-Louis Michel of the French ocean-exploration organization IFREMER (Institut Francais de Recherche pour L’Exploitation de la Mer). “These were men of the deep, men I knew and greatly respected.” Michel and Ballard had first teamed up in 1973 on a research expedition to the mid-Atlantic ridge, a large underwater mountain range.

For Ballard, IFREMER, and the U.S. Navy, the Titanic was essentially a target to test prototype underwater vehicles that would give humans a “telepresence” on the ocean floor. Telepresence, a word coined by Ballard, means using video technology to project one’s mind to the seafloor without physically descending to it.

Trim and wiry, a veteran of the French navy’s submarine exploration squad, Jean-Louis Michel initiated a thorough study of all the logbooks and nautical records bearing on the Titanic’s sinking. “Based on these historical data,” Michel explained, “we drew on our charts the probable area where the Titanic should be, somewhere inside a square that was 12.5 miles on a side. By June of 1985, we were ready to go.”

Ballard and Michel were uncertain about the clarity of the water at the site of the wreck. “You have terrific bottom currents running along this area stirring things up,” explained Ballard. “We were concerned that our cameras would be of little use in an area of very poor visibility.”

They had closely researched a severe 1929 earthquake, which shook the whole Grand Banks area off Newfoundland where the Titanic sank. A huge landslide raced as fast as 35 miles per hour down the slope from the continental shelf to the abyssal plain thousands of feet below. “One of our questions,” Ballard said, “was whether this landslide had affected the wreck.” They wondered if their images would show “acres of mud or, if lucky, the bones of the Titanic.”

Michel and his team left Brest, France, aboard the French research vessel Le Suroit on July 1, 1985. “We got to the Titanic’s area eight days later. On July 11, we began ‘mowing the lawn.’ That’s the term used for the meticulous sweeping back and forth with the imaging and listening equipment to cover every square foot of the search area.”

At the end of thousands of meters of cable, Le Suroit towed a “train” of sensing devices. First came a five-meter-long acoustical-system vehicle, nicknamed Poisson (“Fish”) by the French. It contained side-scan and vertical sonar units. Then came a long cable trailing a magnetometer to detect anomalies. “With side-scan sonar,” Ballard explained, “you are searching for the main wreckage, which will show up as a large radar blip on the sonar. At the same time, the magnetometer tells you if what you are looking at is metallic.”

“It took us nearly two hours to get the whole apparatus into position,” Michel explained. “And every time we had to pull it in, it took another two. Strong currents forced us to retrieve Poisson after every ‘mowing,’ and then go back to the starting point and lower it again.”

Compounding the problem was the deteriorating weather, which developed into a 36-hour-long gale. When the search was resumed, Michel recalled, “We had searched an area three times the size of Paris, and we had christened the towed acoustical system successfully. Still, we were very disappointed.”

The last day assisting Le Suroit was August 7, and as she prepared to sail to the French island of St-Pierre off the coast of Newfoundland, Michel and Ballard saw a rainbow to the south. It seemed an omen of good luck.

“That’s It!”

On August 13, Ballard and Michel rendezvoused in the Azores with the 245-foot, 2,100-ton Woods Hole research vessel Knorr, and two days later set sail for the Titanic search area 3,862 kilometers away.

The co-chief scientists were now in reversed roles, Ballard heading up the search while Michel acted as head of the noon-to-4 p.m., midnight-to-4 a.m. watch. “Because it is the most demanding physically, you always put your best crew on the 12-to-4 shift,” Ballard said, and that was the slot assigned to Michel in the small “control van” erected on the starboard side of the aft deck.

The search area contained three different types of terrain: a canyon with many tributaries; a sand-dune area not unlike the Sahara; and part of a large mudslide, the possible aftermath of the 1929 earthquake. “We made an assumption,” Ballard said, “based on all the evidence at hand, that the wreck would be a ‘plume’ of debris about a mile long, and that it would be oriented basically north and south.” So instead of “mowing the lawn,” they established a search grid of east-west lines—and by sending down a video camera, they improved chances of identifying small debris.

Two new deep-sea probes, Argo and Angus, were used in the search. The more critical was Argo, a sledlike submersible the size of an automobile. was equipped with sonar, powerful strobe lights, and sophisticated video equipment. Like the French acoustical system, Argo was pulled by a steel-jacketed cable with a breaking strength of 30,000 pounds that carried power down to the submersible and data back up to the surface ship.

As the days went by, hope for finding the wreck waned. A routine of keeping eyes glued to the video monitors settled in. Ears listened to rock and country music, and mouths bulged with buttered popcorn. August was slipping away, and the “weather window” was about to slam shut.

On the night of August 31 to September 1, Jean-Louis Michel came on duty in the control van for the 12-to-4 a.m. watch. Michel took his position at the ship-driving console. With him were six others on the graveyard watch including the navigator, the video operator, and the sonar expert. Ballard went to his quarters for the night.

As the Knorr was moving cautiously over its course, the unblinking eye of Argobegan to record pieces of debris. Gray images of coal and lengths of metal piping slid across the video screen. This could be it, Michel thought, his excitement mounting. “We watched for perhaps five minutes as other fragments came into view. Then, suddenly, there was the unmistakable image of one of those giant boilers!”

While people stared at the image, an air of intense surprise and wonder permeated the control van. “Somebody should wake up Bob Ballard,” Michel said. But nobody wanted to leave. It was too emotional a moment.

Just minutes later, at about one in the morning, cook John Bartolomei knocked at Ballard’s door, stuck his head in the cabin, and reported, “The guys think you should come down.”

Ballard hurried to the control center, stepping into the soothing red light of the large room for his first look at the video image of the boilers on the monitors. “That’s it!” he exclaimed.

As word of the discovery spread throughout the ship, the control van filled with excited crew members and scientists. Amid the jubilation, Ballard later recalled that “the human side hit us. It was so close to the time the disaster occurred—the Titanic sank at 2:20 a.m.—that it seemed appropriate to make a gesture. It was spontaneous. I just said that some of us wanted to have a moment of silence. If others wanted to join us for a brief ceremony, they could.

“I don’t remember how many came. We were very quiet. All I could think was that those many lives had been lost needlessly. If only there had been enough lifeboats. If only the Californian’s radio operator had been awakened. To finally put those souls to rest was a very nice feeling.”

A Warmth of Remembrance

With time running short, Ballard and Michel flew Argo gingerly around the wreck some 13,000 feet below the heaving seas.

More pictures emerged on the Argo’s video screen: part of the Titanic’s bridge, a gaping hole where the forward smokestack once stood, empty davits. Later, the prow appeared with its foremast, and anchor chains looking as though they had turned to stone. Watching these pictures, Ballard felt “like an archaeologist opening a Pharaoh’s tomb.”

“Flying over the hull,” Ballard added, “was like walking on egg shells.” It was determined that the forward mast had toppled, but at one pointArgo flew so close to the Titanic that it bounced off the base of one of the stack mounts, picking up a small smear of paint on its steel frame.

Ballard decided to approach the ship from the stern, but, to his surprise, he could not find it. Had it broken off somewhere beyond No. 2 stack? He lowered Angus, a still-camera submersible, to get close-up, high-quality 35-mm color photographs. Developed later, they showed the bow section covered with “a thin dusting of sediment, like a gentle snowstorm.” Etched indelibly into the mind were images of wine bottles, cut-glass windows, a mattress frame, the ship’s telegraph, the crow’s nest. But no poop deck, no stern.

The Knorr, which had been allotted only one month for this expedition, was now scheduled to return to Woods Hole. On the trip back, Ballard and Michel discovered that they had seen the stern after all—in pieces. A review of the film images disclosed that it was contained in a debris plume extending more than a mile behind the wreck.

Capt. Richard Bowen of the Knorr later wrote about the voyage home: “On the four days’ transit, the airwaves, which are normally filled with merchant-ship traffic, would become oddly quiet as other ships held their traffic and listened to ours. On ships around the world, officers and seamen must have said, ‘Somebody finally found the Titanic.’

“Four generations of mariners have grown up hearing of the Titanic, and now the mystery of her location is finally solved.”

For Ballard and Michel, the great ship lying over three kilometers below them lived for a moment, again, as she had those seven decades before: sleek and eager to dash across the Atlantic Ocean, her seven bright rows of portholes and windows exuding golden light. She symbolized an age of ease and graciousness, of pride and confidence in the powers of man. Now, as an avid press broadcast the news received from the Knorr, the world seemed to reminisce, to mourn, to feel an ache in the heart and a warmth of remembrance for those brave victims who perished on that great ship so long ago.