The Complicated Ukraine-Russia War, Explained in Simple Terms

Updated: Apr. 06, 2023

As war erupted in Ukraine, many people wondered how things got to this point. Here, we break down Russia and Ukraine's long, often-strained relationship and what the future may hold for Ukraine and the world.

The Reader’s Digest Version

|

“Explosions started again,” wrote Svitlana, via text message from besieged Kharkiv in northeast Ukraine shortly after the Russian invasion began. “Today it was stronger. That means it was closer than yesterday.”

The 23-year-old choreographer, whose real name we are keeping secret for her protection, had just spent the second night of the Ukraine-Russia war sleeping in her bathtub, away from windows and the danger of jagged shrapnel and broken glass from bombs exploding outside. For one night, at least, she was safe, though Russian tanks were reported on the outskirts of Ukraine’s second-largest city. She tried to stay that way, while trying to predict when she would have to flee.

Like many of Ukraine’s 44 million citizens, Svitlana chose to stay as long as she could. Despite the overwhelming odds, she had faith that her fellow citizens would remain strong and ultimately send the invaders back home. While Ukrainians try to find hope in dark times and people around the world do their best to help Ukraine from afar, the situation in the country remains grim. On the one-year anniversary of the war, getting money is difficult, store shelves are bare and public transportation has largely been shut down. With a few exceptions, most subway stations are being used as bomb shelters.

Kharkiv is a strategically important city, just 25 miles from the Russian border, and a midway point between the breakaway regions of Luhansk and Donetsk in the east and the capital of Kyiv to the west. Historically it’s an industrial hub, the city that birthed the legendary T-34 tank that the Soviet Red Army used to drive the Nazis out of Russia and chase them all the way to Berlin during World War II.

Ukraine was a republic of the USSR then, which it remained until 1991. The collapse of the Soviet empire offered the opportunity for freedom and independence, which Ukraine claimed for itself on Aug. 24 of that year. It was a major step in a history between two countries and two peoples whose destinies have been intertwined for more than 1,000 years, but whose differences have long simmered, only to erupt on a cold February night in 2022.

If you’re confused about what led up to the Ukraine war, you’re not alone. We’ve talked to experts in the region to break down the complicated history between these two countries and explain what this conflict means for the world.

Russia and Ukraine share a long, uneasy history

Despite Slavic kinship, extensive intermarriage and similar yet distinct languages, Ukrainians and Russians tend to harbor cultural peevishness, sometimes reflected in a stern, prideful assertion of one’s nationality, similar to how an Irishman might bridle at being called British.

Resentments borne of centuries of friction run deep still today, with most Ukrainians just a couple of generations removed from the Holodomor, the great famine that killed millions of Ukrainians in 1932 and 1933. The deaths—estimated between 3.5 and 7 million by most scholars—were caused by policies enacted by Soviet leader Josef Stalin. Ukraine was, and still is, one of the largest producers of grain in the world, but the Kremlin shipped grain out of Ukraine while its people starved. Although there is debate over the true goals of those policies, most Ukrainians, as well as 16 countries, recognize it as a genocide spurred by Stalin’s fear of a growing independence movement in Ukraine.

“Soviet secret policemen organized teams of activists to go from house to house in parts of rural Ukraine, confiscating food. Some 4 million Ukrainians died in the famine that followed. Mass arrests of Ukrainian intellectuals, writers, linguists, museum curators, poets and painters followed,” writes historian Anne Applebaum, whose 2017 book Red Famine examines the causes and consequences of the Holodomor. She notes that Stalin’s deadly oppression of Ukraine instilled a distrust of power, particularly that exercised by Moscow, and invigorated Ukrainian national identity.

Why didn’t diplomatic efforts stop the Ukraine-Russia war?

Many people may wonder why this had to come to bloodshed. Surely something could have been done to prevent it, right? Steven Horrell, senior fellow at the Center for European Policy Analysis and a former Director of Intelligence in the U.S. European Command, doesn’t think so. “You have to remember, this is a war of choice,” Horrell says. “Ukraine never threatened the territory or the people of Russia. What threatened Putin was the idea of a democratic Ukraine seeking to align itself with the EU and the West.”

An active, politically engaged population within his presumed sphere of influence is simply something Putin cannot abide, many experts say. “Vladimir Putin has an imperialist, revanchist view of Russia and his role in Russian history,” says Evelyn Farkas, a former U.S. Defense Department official in charge of Russia and Ukraine. “He wants to recreate something like the Russian Empire. But he wants to do it not to solidify his legacy but his hold on power. He’s focusing on Ukraine because Ukraine chose democracy, and a thriving democracy right across the border is very threatening to him.”

As evidence, Farkas points to Putin’s choice to annex Crimea in 2014 and back separatists in eastern Ukraine’s Donbas region, following closely on the heels of 2013’s Maidan Revolution, when a popular uprising ousted Ukrainian president and Putin ally Viktor Yanukovich after he reneged on a deal to establish economic ties between Ukraine and the European Union, a deal supported by 58% of Ukrainians. More recent evidence can be seen in Putin’s sending assistance to Belarusian President Alexander Lukashenko in 2020, when he faced massive public uproar over an election that was generally thought to be rigged in his favor. And in January 2022, Putin sent troops into neighboring Kazakhstan to help quash demonstrations in that former Soviet republic, leaving 227 dead. (Interestingly, Kazakhstan refused to provide troops to assist Russia’s Ukrainian invasion.)

Why invade Ukraine now?

Farkas has been critical of the West’s response to Russia’s annexation of Crimea, saying Western timidity after that act emboldened Putin for further acts against Ukraine and may have led him to believe invading Ukraine would be met with a similarly weak global response.

“The last time something like [a military annexation] happened was in 1991, when Saddam Hussein marched into Kuwait and said, ‘This is Iraq now,'” says Farkas. “The international community immediately said you can’t alter borders using military force, and then coalition forces went in to force Hussein out. When Putin seized Crimea, there wasn’t the same response. Because Russia is on the UN Security Council, we weren’t going to get a resolution condemning them, but we got a majority of the general assembly to declare it an illegal act. But there was no action to follow after that to highlight for the world how dangerous the Crimea annexation was.”

Policy analyst Dahlia Scheindlin suggests that Crimea was one of many offenses against the geopolitical order—some committed by Western countries—that enabled Putin’s aggression. “For months ahead of the invasion of Ukraine, the world was scrambling to guess what Putin wanted,” she writes in Foreign Policy. “But Putin may well have been tallying the erosion and inconsistencies of international norms—to be sure, with his contribution—and concluding that the vaunted international system wouldn’t stop him.”

While diplomacy was unable to prevent Russia’s Ukrainian invasion, Horrell credits the Western countries for taking a hard line against Putin’s demands. Indeed, what many (including Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky) thought was nothing more than fearmongering was actually exposing Putin’s playbook before he put it into action. “Releasing declassified intelligence to get ahead of the misinformation and disinformation was very effective” in undermining Putin’s plans to use a false-flag operation to instigate war and then install a puppet regime, “because we usually lose that narrative/information battle,” Horrell says. This was something Putin had been trying to do shortly before the invasion, blaming violence such as a car bomb and a gas-pipeline explosion on Ukrainian separatists, when, in fact, these incidents may have been perpetrated by Russians and subsequently used as an excuse for going to war.

Putin’s justification for war

While the consensus among Western experts is that Putin’s immediate motive for the Ukrainian invasion was to oust Zelensky and suppress the West-leaning, anti-corruption, pro-democracy movement that elected him, Putin offered many shifting rationales leading up to the attack.

The NATO claim

Most prominently, Ukraine possibly joining NATO was touted as a provocation. But as Horrell and Farkas point out, it was never really on the table. And as Michael McFaul, former U.S. Ambassador to Russia, and U.S. Military Academy Director of International Affairs Curriculum Robert Person note in the Journal of Democracy, Putin expressed no concern about it on several occasions.

Moreover, McFaul and Person write, “Nothing in the past year in Ukraine-NATO relations has changed. It is true Ukraine aspires to join NATO someday. (The goal is even embedded in the Ukrainian constitution.) But while NATO leaders have remained committed to the principle of an open-door policy, they have also clearly stated that Ukraine today is not qualified to join. Putin’s casus belli is his own invention.”

In any case, the record shows that NATO never made a concrete pledge not to allow former Soviet states into its fold. Horrell points out, however, that Russia signed the 1994 Budapest Memorandum guaranteeing Ukraine’s territorial integrity in exchange for Ukraine surrendering its Soviet-made nuclear arsenal; Putin’s seizure of Crimea was a flagrant breach of that contract.

The Nazi/genocide claim

When he declared war on Feb. 24, 2022, Putin promised “demilitarization and de-Nazification of Ukraine” and an end to an alleged “genocide” against ethnic Russians in the Donbas region. This claim has even longtime Kremlinologists scratching their heads. Though it’s true that a faction of Ukraine’s army has been linked to the neo-Nazi paramilitary group Azov Battalion, it’s also true that Russia’s armed forces and paramilitary groups in Donbas, like the White supremacist Russian Imperial Movement, preach fascist ideology. Also, it should be noted, Zelensky is Jewish and lost many family members in the Holocaust, while others in his family fought against the Nazis as soldiers in the Soviet Red Army.

Furthermore, there has been no evidence of any mass killings, let alone genocide—something that makes the pretense of humanitarian intervention offensive to experts in the field.

“Putin has offered little proof to support his allegation—which he has repeated several times since 2015,” writes Alexander Hinton, Director of the Center for the Study of Genocide and Human Rights at Rutgers University. “But these Russian claims have been found by a number of observers to be baseless and even fabricated, serving only to justify a military intervention.”

The “Ukraine is not a country” claim

The most brazen and bizarre of Putin’s claims is that Ukraine is not a real country. Of course, like many countries in Europe, Ukraine has been occupied by many empires. Since its early days as the center of the medieval state of Kievan Rus, in part or in whole it has been under the thumb of the Mongols, the Ottoman Turks, the Russian Empire and the Soviet Union, among others. But throughout the centuries, Ukrainian national identity remained, says John Vsetecka, a historian and Fulbright scholar. “From a historical standpoint,” he adds, “I can tell you that Putin’s [Feb. 21, 2022] speech was naive, misguided and completely inaccurate.”

How is Ukraine fighting back?

Whether Russia’s invasion of Ukraine ultimately succeeds depends on many things, including how you define success. From the start, the Ukrainian people showed their commitment to resist any occupation. Viral video of an elderly Ukrainian woman in occupied Kherson offering sunflower seeds—the national flower of Ukraine—to a Russian soldier to keep in his pocket “so at least flowers will grow when you lay down here [to die]” displays bravado and resolve that has inspired many inside and outside Ukraine.

While the Ukrainian army has racked up impressive victories against its more powerful adversary, civilians have joined the fight, including prison inmates with combat experience. And private businesses like bars and breweries have turned their efforts to making improvised weapons, like Molotov cocktails.

“My friends in Ukraine are academics, students and professors, but they’re taking up arms to protect their country,” says Vsetecka, who was in Kyiv until Jan. 26, 2022, when he and his research cohort were evacuated to Poland. He says the Ukrainian people are stoic and “stubborn, maybe to a fault.”

That refusal to buckle was evident in the widely seen video of a Russian warship warning a garrison on a small Black Sea island to surrender or face immediate attack. Their response? “Russian warship: Go [expletive] yourself.” Miraculously, all 13 men and women on the island survived, according to the Ukrainian Navy, though they were eventually captured when their ammunition ran out. But the stubbornness they demonstrated may prove to be the factor that ultimately decides the conflict.

“We’re seeing people—regular people, men and women—line up to pick up weapons by the thousands,” says Horrell. “Any puppet leader installed by Putin is going to have an extremely hard time trying to rule. There’s a mistaken belief that ‘Russian-speaking’ means ‘pro-Moscow,’ and Putin’s mistake is going to prove costly in the long run.”

Who is Volodymyr Zelensky?

Chief among Russian-speaking Ukrainians opposed to Russian occupation is Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky. He’s become something of a cult hero to Western observers, reportedly refusing a Russian offer of safe passage to exile in exchange for his resignation, and rebuffing an American offer to evacuate him out of Kyiv by saying, “The fight is here. I need ammunition, not a ride.”

Most Americans generally know that Vladimir Putin was a KGB spy during the Soviet era, and that since 1999 he has wielded ultimate power in Russia; he even altered the Russian Constitution so he can continue to rule until 2036 and enjoy lifetime immunity from criminal prosecution. However, until recently, few knew much about the slightly built, gravelly voiced man on whose shoulders the hopes of Ukraine rest. Zelensky rose to the presidency, ironically, from his role in the TV sitcom Sluga Narodu, or Servant of the People. In it, he played a high school teacher whose videotaped rant against government corruption goes viral and leads to a shocking victory in the presidential election. In the show (episodes of which can be found on YouTube with English subtitles), his efforts to root out entrenched corruption earn him loyal friends and dangerous enemies.

The show’s popularity and its anti-corruption message gave Zelensky—who ran unironically as the Servant of the People Party candidate—a landslide victory, with 73% of the final vote. His words upon being elected, as reported by the Washington Post, would be foreshadowing: “To all Ukrainians, no matter where you are, I promise that I will never let you down.”

“People didn’t have a lot of confidence in him, as a political novice, when he was first elected,” says Emily Channell-Justice, director of the Temerty Contemporary Ukraine Program at Harvard University. Few figured he’d stand up to Putin. “A lot of them thought he’d bolt at the first sign of attack. But he’s stayed in Kyiv to lead.”

“To every Ukrainian I’ve talked to, he’s been a source of stability in an unstable time. He’s target No. 1 for the Russian military, but when he had the opportunity to leave, he decided to stay,” says Vsetecka. “Historians are bad at predictions, but I would say that however this ends for Zelensky, whether he survives or not, he will be remembered as one of the great leaders in the history of Ukraine … and probably the world.”

More Stories About the War in Ukraine

|

How will this end?

After a full year of continuous fighting, we are no closer to answering this question. Delegates from both countries have tried to negotiate a cease-fire, and possibly also a peaceful resolution, while Western diplomats and others have sought ways to stop Russian aggression. But predicting Putin’s moves has proven difficult.

And while it’s always hard in times of war not to reduce the leader of the other side to a cartoonish evildoer, in the current situation, the characterization is hard to avoid. “He’s killed innocent people. He’s jailed and poisoned his political adversaries. He let his troops shoot down a civilian airliner. He’s shown total disregard for human life,” says Farkas. “Putin is absolutely a villain.”

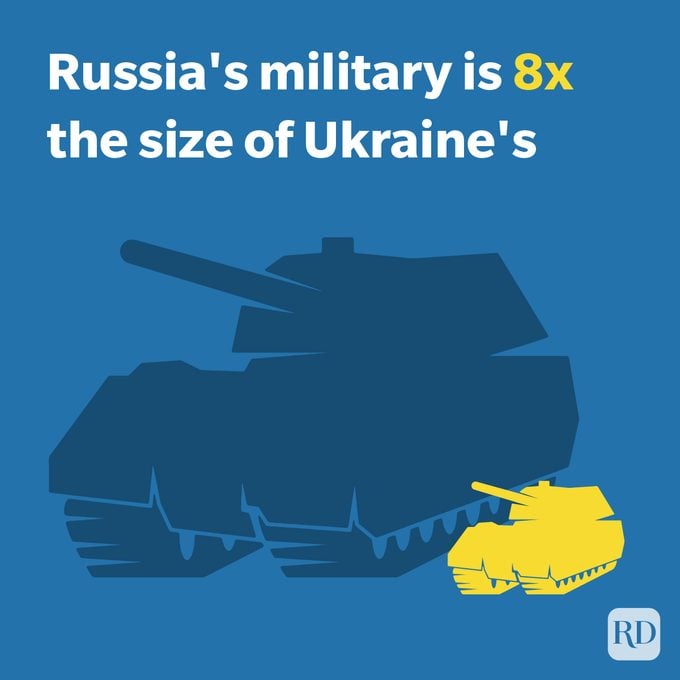

Horrell agrees, and he fears that a prolonged Ukraine-Russia war will make Putin more ruthless to avoid losing face. “Militarily, Russia has all the advantages in equipment and manpower. But in terms of will, Ukraine has the advantage, and the people and the military have acquitted themselves well,” he says. “But the longer Ukraine can hold, the fewer self-imposed constraints you’ll see from Russia and the more indiscriminate killing you can expect.”

Amnesty International, the International Red Cross and other organizations have decried human rights abuses and war crimes, including targeting civilian populations and terrorizing Ukrainians with sexual violence. Meanwhile, the United States, the EU, Australia and other countries have imposed broad sanctions against Russia. For example, early in the war, Germany halted the $11 billion Nord Stream 2 gas pipeline project, and other countries closed off airspace to Russian airlines and, most pointedly, blocked several Russian banks from the SWIFT international banking system—essentially preventing them from doing business outside Russia. Other sanctions have targeted the oil industry, technology and transportation, as well as Putin and members of his inner circle personally.

“The intent of these sanctions is to hurt the regime without hurting the Russian people,” Horrell says. “[These] actions target the inner circle of oligarchs and the powerful around Putin—and it’s a very small circle. Can we get them to find an off-ramp, to change course, to reverse the decision to pursue a war of choice? That’s a very tall task.”

For the first time in its history, the EU has purchased weapons to help supply the Ukrainian war effort. Zelensky offered his gratitude, but he has also said a fast track to EU membership for Ukraine would be an important demonstration of European support—and promptly signed an application to join.

How can you help?

Watching the bloodshed on the streets of Kyiv, Odessa, Kharkiv and throughout Ukraine, as well as the streams of millions of Ukrainian refugees escaping to safety in countries to the west, many Americans wonder what regular folks can do to help. According to Channell-Justice, there is a lot we can do from afar—for both people who are staying in Ukraine and those who are fleeing the country.

She recommends contacting your representatives in Congress to let them know your concerns, donating money to reputable relief organizations providing assistance to Ukraine as well as refugees, and fighting misinformation and not spreading it. She also recommends participating in public shows of support and letting your voice be heard. “This may not seem important, but Ukrainians have messaged me to say it’s very heartening to see big crowds across the world come out in their name,” she says.

For their part, tens of thousands of Russians have taken to the streets, at great personal risk, to protest against the war. Many have been arrested. Despite being fed a steady diet of pro-Kremlin advocacy and faked videos by state-owned and Putin-affiliated media, they have lent their names to the peace movement. More than 4,000 scientists and journalists signed a public letter calling for an immediate end to the violence against Ukraine, as have thousands of Russian tech workers, while celebrities, public figures, media companies and activist organizations have joined the public cry condemning the war.

“I think it is worthwhile to praise those Russian people who have been brave enough to protest the invasion. Thousands have been arrested, and not gently,” Horrell says, adding that if the wider Russian population can be weaned from propaganda, “even more will speak out, hopefully find safety in greater numbers and even effect change.”

Meanwhile in Karkiv …

On the early morning of Feb. 27, 2022, Russian troops entered the center of Kharkiv, unleashing violence that reportedly claimed a large number of civilian victims. Svitlana sent a message saying she couldn’t leave the city safely because public transport had stopped running and the roads were not safe. But, she said, she had enough food and water to keep her going for a few days. Her messages were quietly resolute, if not entirely optimistic.

“Everything will be all right,” she wrote. “They want us to panic so we give them our cities and our country. I will do my best. I see all of this. I believe that Putin will pay for what he has done.”

Sources:

- University of Minnesota: “Holodomor”

- Holodomor Museum: “Worldwide Recognition of the Holodomor as Genocide”

- Carnegie Endowment for International Peace: “Whose Rules, Whose Sphere? Russian Governance and Influence in Post-Soviet States”

- Atlantic Council: “How modern Ukraine was made on Maidan”

- Foreign Policy: “When Recognition Is Reckless”

- Journal of Democracy: “What Putin Fears Most”

- VOA: “Russia’s Putin Says Western Leaders Broke Promises, But Did They?”

- Washington Post: “Putin says he will ‘denazify’ Ukraine. Here’s the history behind that claim.”

- John Vsetecka, historian and Fullbright scholar

- Emily Channell-Justice, director of the Temerty Contemporary Ukraine Program at Harvard University

- EuroNews: “Ukraine war: EU to buy and deliver weapons to Kyiv, says Ursula von der Leyen”

- The Guardian: “‘Pure Orwell’: How Russian state media spins invasion as liberation”