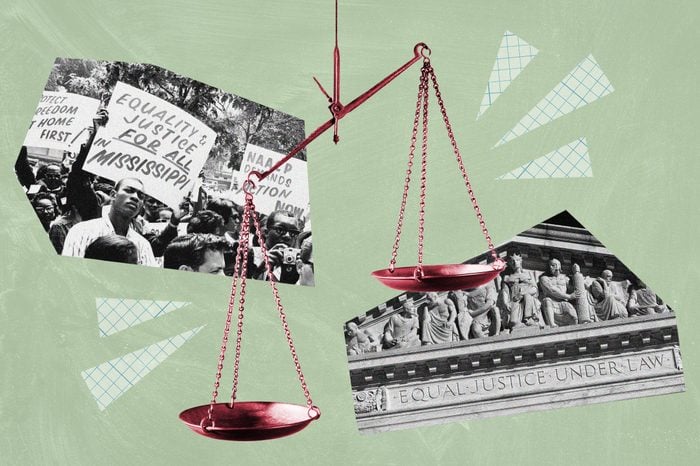

What Is Critical Race Theory, and Why Is It Important to Understand?

Updated: Nov. 28, 2022

Critical Race Theory has been alternately criticized and celebrated, but do you actually know what it is? Here, experts define this controversial concept and explain its real-world implications.

If you’ve been paying attention to cable news discussions or political debates about institutional racism or have listened to podcasts about race over the last year, you’ve probably heard about Critical Race Theory (CRT). While this theory has been around for decades, it has suddenly become a hot topic, and the mere mention of CRT can get tempers flaring. But what is Critical Race Theory, exactly?

At its core, it encourages discussions of race and racism in all of its complexities, from our country’s difficult history to the ripple effect that history still has on our world today. Traditionally taught in higher education, CRT has never actually been a part of the American grade school curricula. However, politicians have been using the concept, along with the Black Lives Matter movement, to rile up their bases, and the resulting polarized debate has not clarified things for most people. Let’s take a look at what CRT actually means and how it affects you, students, and society in general.

So, what is Critical Race Theory?

CRT dates back to the 1970s when it originated as a law school concept. It asserts that racism is embedded in American laws and institutions, and examines the roles that race and racism play in those laws. Over the years, CRT studies have grown beyond just an examination of the law to include American studies, education, and political science.

Typically only taught in graduate courses, this theory became part of the mainstream conversation in the wake of White Minnesota police officer Derek Chauvin’s May 2020 murder of George Floyd, a Black man. Amid protests and public outcry, it was a moment when more people began looking critically at racial issues in policing and other American institutions. But during a September 1, 2020, appearance on Fox News, conservative journalist Christopher Rufo conflated anti-racist trainings in federal workplaces with CRT. Within days, the Trump administration ordered an end to such trainings in federal agencies, and discussions about CRT began to pick up steam. Suddenly, people across the country were looking at discussions about race and CRT as one and the same.

Who coined the phrase Critical Race Theory?

Critical Race Theory was largely shaped by law professor Derrick A. Bell Jr., the first Black tenured professor at Harvard University. He examined the effect of race and racism on the country’s laws and society as a whole. But Kimberlé W. Crenshaw, an attorney, civil rights advocate, and law school professor, is credited with coining the term during the first Critical Race Theory workshop, held at the University of Wisconsin in 1989, explains Angela Onwuachi-Willig, dean and professor of law at Boston University School of Law and a CRT expert. Some 20 lawyers and legal scholars attended that gathering to define the realities of race and develop the concept of CRT. One of the issues they examined and built CRT around was how the law produces and reproduces inequality in society.

“People talked about the law—and even [do] today—as though it were purely objective and neutral,” says Onwuachi-Willig. “There was no attention paid to the fact that law is man-made. There are a lot of cases and statutes written by people who think of their own experiences as normative, and they were writing out of their experiences…as though they were standards that applied to everyone.” Anyone who didn’t share those experiences was at an automatic disadvantage, she adds. After all, for hundreds of years, one group—White men—wrote the laws and based them on their own experiences and biases, and people of color were always at a disadvantage.

“Obviously, a goal of the law is to be neutral and objective, but if we don’t recognize that it isn’t, then we’re only going to reproduce certain inequities,” says Onwuachi-Willig. “So that was part of the conversation [during the original CRT workshop].”

What are the central tenets of Critical Race Theory?

Proponents of Critical Race Theory sometimes disagree about what should be defined as core tenets and even how many there are. Although CRT and discussions about it are complex, there are a number of widely held important concepts. At their core, they reflect one central idea: Racism is embedded in all of our systems, and if we don’t acknowledge and address it, it is not simply going to disappear.

1. Race and racism are social constructs

Put simply, according to CRT, the concepts of race and racism are human social inventions. There is nothing biological about it—racial categories change from country to country based on a variety of factors. That’s the reason, Onwuachi-Willig explains, that proponents of CRT seek to make people understand the complexities of racism and how it operates and persists in American society. There are, for example, subtle acts of racism. There are issues around structural access. There is implicit bias. All of these things play a part in why racism continues to exist, even when people are trying not to be racist.

2. Racism is not about individual actors

Racism is built into our systems and exists regardless of how well or how poorly individual people within those systems act. “There is a centrality of racism,” says David G. Embrick, PhD, an associate professor of sociology and African studies at the University of Connecticut. “It’s not based on the actions of individuals. Take those few bad apples out and the racist policies and practices will continue, because of how they’re embedded within our legal structure, our educational structure, and the workplace.”

3. Racism is ordinary

Racism is not an aberration—it is part of the everyday experience for people of color. “The Bad Apple is a story we tell that says that racism is unusual,” says Onwuachi-Willig. “But racism is literally built into systems of many of our institutions, including the law as an institution.” And although the laws that govern White and Black people are the same, they are not always applied equally. For example, African Americans are imprisoned at five times the rate of their White counterparts.

4. People experience the world according to their combined gender and racial identities

Another significant CRT tenet, intersectionality, also was coined by Crenshaw. In a 1989 paper for the University of Chicago Legal Forum, she argued that we can’t ignore how people’s race and gender influence their experiences. For example, a heterosexual Black woman will experience the world—and discrimination—very differently than a White gay man; people are shaped by the intersection of their various categories.

The concept dovetails with anti-essentialism, the idea that there is no definitive archetype of a person. “When we think about the essential person in any particular group, we should have a complicated understanding that there are lots of different kinds of people,” says Onwuachi-Willig. “When we’re talking about women, we’re talking about all kinds of women. When we’re talking about gay people, we’re talking about all kinds of gay people.”

5. People of color only make societal advances when their interests meet those of the predominantly White power structure

The Interest Convergence Principle, developed by Bell, maintains that people of color generally only experience gains and advances when their interests converge with those in the decision-making White elite. “Bell wrote a famous article where he talked about how Brown v. Board of Education wasn’t specifically about moral will or moral good—there were a lot of reasons why the United States was concerned about its image on the international stage,” says Onwuachi-Willig. “It was in the middle of the Cold War and being heavily critiqued by all these countries about how it was treating African Americans. So, all these things [came] together to make it such that the United States needed to have that Brown decision.”

6. A color-blind approach will not end racism

Saying “I don’t see color” doesn’t mean we’re moving toward equality. In order to combat racism, Onwuachi-Willig says, people have to identify the policies and practices that take racism into account; they also have to consider the history of the country, the ways in which the past and the present have subordinated certain groups, and how those things may still affect them.

7. A racial hierarchy benefits people in the dominant group financially and psychologically

Another important tenet of CRT is that racism benefits people within the dominant group of society in a variety of ways, including having a higher social status simply because they are part of the dominant group. “People always ask, ‘Why don’t the White poor classes and poor classes of people of color form these powerful coalitions?’ If you look at it historically, part of it is the psychological wages of Whiteness and what it means to be White,” explains Onwuachi-Willig about a concept discussed by W.E.B. Dubois. “There’s a psychological benefit, meaning that ‘I’m not at the bottom as long as my whiteness inherently makes me better than these other people.'”

8. Different groups are racialized differently

Although all ethnic groups are racialized, they are racialized in different ways. One example is the model minority myth. It attributes purely positive characteristics—often relating to intelligence, academic achievement, or work ethic—to one minority group, and uses those things as measuring sticks against others. In the United States, Asian Americans typically are stereotyped as the model minority. “There’s a different kind of racism that Asian Americans experience versus Black people or Latinx people,” says Onwuachi-Willig. “I think people of color, because of our very different experiences in the United States, bring a unique voice to the table about a variety of issues, and that is important. That’s why diversity matters.”

9. People in racial minorities contradict and downplay negative group stereotypes

Another CRT tenet, known as Working identity and Covering, helps to describe the ways BIPOC (Black, Indigenous, and People of Color) operate in the world as a result of the burdens placed on them and the stereotypes associated with their groups. For example, someone who is “working their identity” tries to contradict the negative stereotypes associated with the group to which they belong. Onwuachi-Willig uses as an example the Black law firm associate who works longer hours than anyone else to counter the stereotype that Black people are lazy.

Often, members of racial minorities also invest a lot of time and energy into downplaying a trait associated with their group. “Covering is downplaying their disfavored trait,” Onwuachi-Willig says. “So, somebody tells a joke at work about a group you belong to and you laugh at it or you downplay it.”

10. It’s important to tell stories about the experiences of marginalized groups

Proponents of CRT also argue that since American history and popular culture traditionally have focused on the stories and experiences of the dominant culture and engaged in whitewashing, it’s important to shine a spotlight on the stories of marginalized groups through counter-storytelling. Embrick explains that understanding the experiences of people who have been oppressed can help people understand their point of view and, ultimately, help combat racism. “The attacks on Critical Race Theory,” he says, “can be sort of seen as a way to minimize or render that history invisible, as if it doesn’t really matter.”

Where is Critical Race Theory taught?

CRT traditionally has not been a part of most K–12 curricula. Typically, these complex issues wouldn’t be introduced until college, law school, or graduate school, according to Onwuachi-Willig. But after Rufo brought up the topic in conservative media and other media personalities started covering it regularly, some began to group it with discussions of White privilege and racism or diversity and bias issues in schools. And that conflating of the issues, along with recent discussions about how to teach the long-term impact of slavery and similar historical ills, has prompted an angry response from some parents and school boards. The result has been a recent spate of preemptive bans on CRT being taught to students. School districts from California to Alabama have decided it can’t be taught in their classrooms; bans are happening on statewide levels, too.

What is the impact of recent bans on teaching CRT in schools?

These preemptive bans may have a chilling effect on students’ overall education in both elementary schools and high schools. For instance, a parent group in Tennessee wants to ban books on Martin Luther King Jr. for being too divisive; the group also objects to lessons on protests during the civil rights movement and school segregation. Meanwhile, one Texas lawmaker is pushing for bans on a range of books, including those about the LGBTQ community and human rights. He even opposes a book written by Ruby Bridges, one of the first Black students to integrate a White school. The bans are also especially problematic where history is concerned.

That said, notes Onwuachi-Willig, most of the bans are poorly written and forbid the teaching of things educators would never want to teach anyway. “I think you can continue to teach what you’re teaching, which is real history,” she says.

As Embrick sees it, the attacks on CRT are an attempt to render invisible the parts of our history that still affect our lives. “I’ve read and heard on TV that we’re creating fractures in our community by talking about racism,” he says. “The fractures are already there.”

The real problem, he adds, is that minimizing and denying the United States’ history and the realities of racism hurts everyone. While the tactic tries to protect the status quo, White people also lose out because they, too, are denied an understanding of American history and why things are the way they are now. “It’s about silencing our [country’s] history,” Embrick says. “And that history is not just history, because it’s very relevant for how people are oppressed today.”

Now that you know what Critical Race Theory is, you might want to take a deeper dive into related topics with these essential documentaries and books about racism.

Sources:

- Angela Onwuachi-Willig, dean and professor of law at Boston University School of Law

- David G. Embrick, PhD, associate professor in Sociology and Africana Studies at the University of Connecticut

- The Nation: “The Predictable Backlash to Critical Race Theory: A Q&A With Kimberlé Crenshaw”

- New York Times: “What Is Critical Race Theory?”

- Columbia News: “What Is Critical Race Theory, and Why Is Everyone Talking About It?”

- Berkeley Law: “The Push to Cancel Critical Race Theory: Scholars Explain Factors Driving the Backlash”

- The Sentencing Project: “The Color of Justice: Racial and Ethnic Disparity in State Prisons”

- Newsweek: “Critical Race Theory Is Banned in These States”

- Bookriot: “All 850 Books Texas Lawmaker Matt Krause Wants to Ban: An Analysis”