Chappaquiddick: The Still Unanswered Questions About Ted Kennedy’s Fatal Car Crash of 1969

Updated: Feb. 14, 2023

What really happened on the bridge on Chappaquiddick Island on Friday, July 18, 1969?

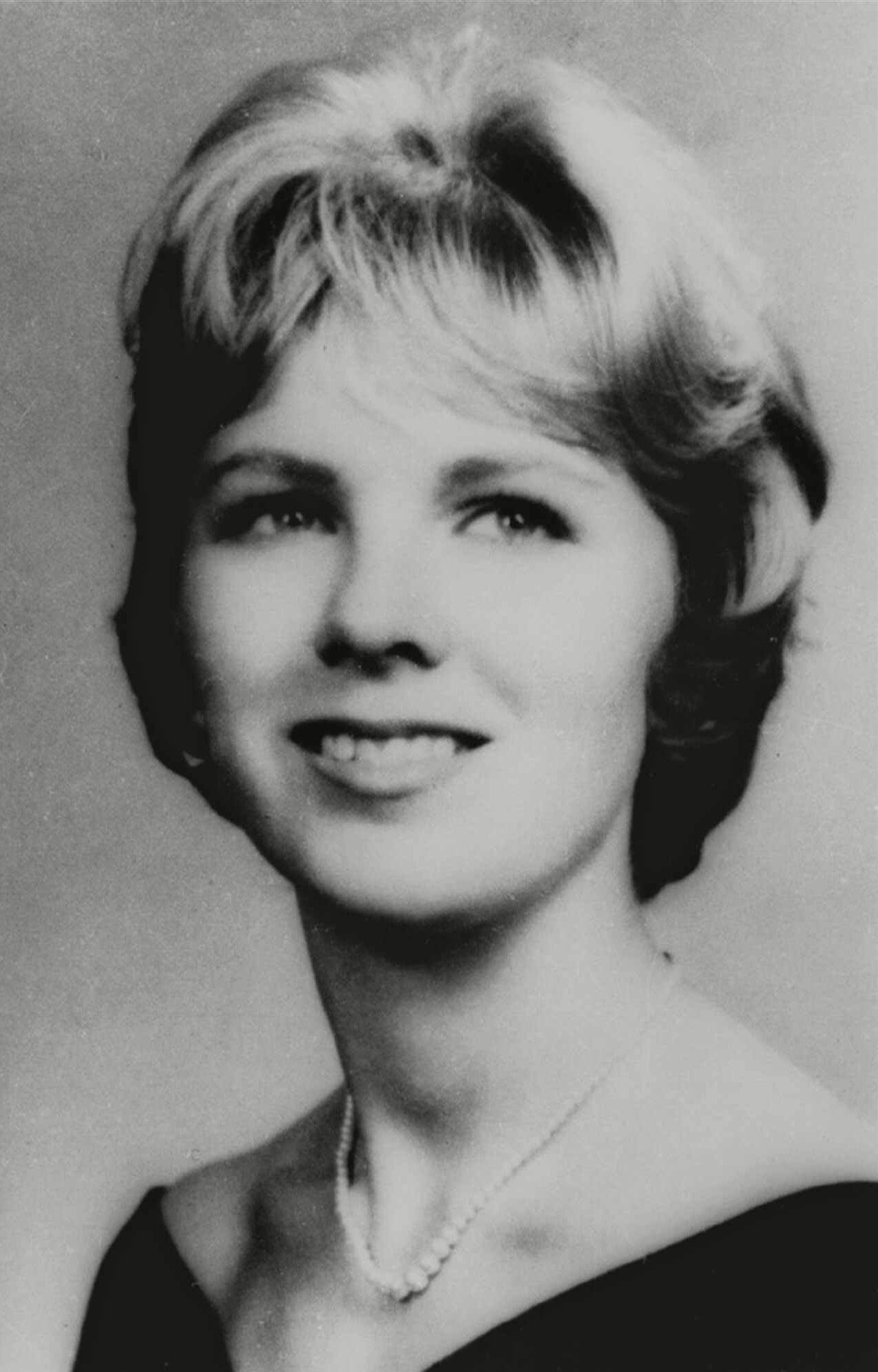

Editor’s Note: In November 1979, Senator Edward Kennedy seemed poised to seize the Democratic nomination for president from incumbent Jimmy Carter. But the aura of inevitability was dispelled when questions were once again raised about the fatal car crash at Chappaquiddick ten years before that left long-time Kennedy-clan campaign worker Mary Jo Kopechne dead in a submerged car off a one-lane bridge near Martha’s Vineyard. Kennedy, who had been behind the wheel of the car, escaped to safety and, for reasons never convincingly explained, waited ten hours to report the incident.

Then came Reader’s Digest’s February 1980 cover story by investigative journalist John Barron. Built around a painstaking re-enactment of the scene and independently commissioned reports on details of the crash and tidal conditions at the time, it contradicted Kennedy’s account. Many blamed our story for helping to reverse Kennedy’s comeback and, ultimately, defeat him.

Now almost 39 years later, we are republishing the landmark cover story to coincide with the debut of “Chappaquiddick,” a film that re-examines the tragic events and its aftermath with fresh eyes:

In the minds of Americans the word Chappaquiddick has come to symbolize tragedy, mystery and perhaps scandal.

Certainly the death of a young woman who died after Senator Edward M. Kennedy drove his car off a bridge on Chappaquiddick Island the night of July 18-19, 1969, remains a personal tragedy for her family and his. The question is: are the events that surrounded that tragedy a matter of legitimate public concern today? Many responsible commentators agree that they are.

• The Boston Globe: “The most famous traffic fatality of the century will almost certainly play a part in the selection of the next President of the United States. It should. Chappaquiddick was not just an auto accident. Many Americans suspect, not without reason, that Kennedy’s handling of its aftermath is another case of a politician stonewalling. And they wonder whether Kennedy would lie to the American people in a more public crisis. Unless he can do something to clarify the episode during the campaign, he is doomed to live under that suspicion.”

• The Wall Street Journal: “…his ability to function as President depends no little on whether the nation feels he is a man it can trust to explain his actions fully and frankly. Without this trust, national leadership is ultimately impossible. Even though the tragedy does not directly involve the conduct of public office, it will be hard for anyone to avoid the questions it raises about credibility and beyond that about character.

“Nor should these questions be avoided. For, as Edward Kennedy announces for the Presidency, voters will have to ask themselves whether they can believe his account of the major crisis of his life and whether they could believe what he would tell them about any crisis of his Presidency.”

• The Los Angeles Times: “The unanswered questions of Chappaquiddick nag even at those who hope he wins.”

• The New York Times: “There ought to be no hesitation to rake over this puzzling affair. If Mr. Kennedy used his enormous influence to protect himself and his career by leading a cover-up of misconduct-and the known facts lead to that suspicion-there would hang over him not just a cloud of tragedy but also one of corruption, of the Watergate kind. And as we know from Watergate, there is no graver question for a President than whether he can be trusted to respect the law.

“All those who had anything to do with the Chappaquiddick affair and its aftermath owe the nation an accounting that in a decade, for some reason, they have never had to give.”

During the preparation of this story, Reader’s Digest repeatedly asked Senator Kennedy for an interview so that he could respond to the deeply troubling questions about Chappaquiddick that have remained unanswered for so many years. He would not agree to meet with us.

Whatever inner turmoil Senator Edward M. Kennedy may have suffered early that morning, he hid it well. Freshly groomed and dressed in white trousers, white loafers and a blue polo shirt, he looked fit and untroubled as he strolled from the Shiretown Inn on Martha’s Vineyard around 7:30 a.m.

On his walk, the husky 37-year-old Senator met a fellow yachtsman, Ross W. Richards, who had won the first heat of the Edgartown Regatta the afternoon before. They exchanged friendly greetings, and Kennedy accompanied Richards back to the inn where they sat on the porch outside their rooms. Betraying nothing unusual in speech or manner, Kennedy chatted amiably about the weather and races until 8 a.m.

Two of his closest friends, Joseph F. Gargan and Paul E. Markham, then appeared, unkempt and “damp,” thought Richards. Kennedy got up at once, went straight to his room with them and shut the door. Kennedy aide Charles C. Tretter passed, and through the window thought he read on the Senator’s face an invitation to enter the room. Upon entering, though, he was abashed because his boss in effect told him to get out.

About 8:30 a.m. Kennedy emerged in the lobby of the inn, ordered copies of The Boston Globe and The New York Times and borrowed a dime from a clerk to make a telephone call. Minutes later, he, Gargan and Markham walked a few blocks to the ferry which continually crosses the 500-foot-wide Edgartown harbor channel separating Martha’s Vineyard from the island of Chappaquiddick.

After the ride, they stood around the ferry landing on Chappaquiddick for 20 minutes or so. Then off the ferry rolled the wrecker from Jon Ahlbum’s service station, and a ferry operator shouted to, them, “Hey, are you aware of the accident?”

“Yes, we just heard about it,” Markham replied calmly.

Now there was no choice. Kennedy finally had to go to the police. Before reboarding the ferry, Kennedy, a lawyer, gave instructions to Gargan, a lawyer, and Markham, a former U.S. Attorney: “Look, I don’t want you people put in the middle on this thing. I’m not going to involve you. As far as you know, you didn’t know anything about the accident that night.”

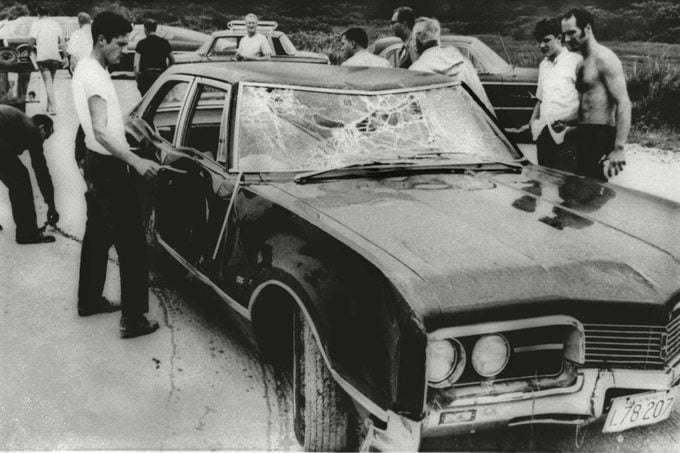

“The Young Lady Is Dead.” While Kennedy and his confidants conferred, other men three miles away tried to cope with what they perceived to be a life-threatening emergency. At the bottom of a seven-foot-deep pond near a narrow wooden bridge, diver John N. Farrar reconnoitered a submerged, overturned, 1967 Oldsmobile sedan. In the light filtering through the water, he first saw, inside, two human feet. Quickly, he slid in through the car’s right rear window, hoping there was still life. But Farrar and the others had come too late. Mary Jo Kopechne’s body was rigid, hands like claws clutching the rear seat, head thrust back and upward toward the surface as if in quest of air.

A big man, Edgartown Police Chief Dominick J. Arena sat in the water atop the car and cradled the body in his arms as he waited for a beat. He was struck by how lifelike and lovely Miss Kopechne looked even in death—blond, neatly attired in a long-sleeved white blouse, dark slacks and white sandals. She was of slight build and seemed not much larger than his own 14-year-old daughter.

The rear license plate was visible, and through a radio check Chief Arena ascertained that the car was registered to Edward M. Kennedy, JFK Building, Boston. After returning to shore, Arena hurried to the Dyke House close by the road some 400 feet from the bridge, intending to phone his men to find Kennedy. But his secretary informed him that Kennedy was at the police station, and put the Senator on the line.

“I am sorry, I have some bad news,” Arena said. “Your car was in an accident over here, and the young lady is dead.”

I know,” Kennedy answered. “Can you tell me, was there anybody else in the car?”

“Yes.”

“Are they in the water?”

“No.”

“Can I talk to you?”

“Yes.”

‘Would you like to talk to me?”

“I would prefer that you came over here.”

At the two-room Edgartown police station in the 141-year-old Town Hall, Arena asked Kennedy for a statement, and the Senator asked if he might submit one in writing. To allow privacy, Arena led Kennedy and Markham into a nearby municipal office where they spent about an hour. Around 11 a.m. Arena read the first Kennedy account, handwritten by Markham, but unsigned:

On July 18, 1969, at approximately 11:15 p.m. in Chappaquiddick, Martha’s Vineyard, Mass., I was driving my car on Main Street on my way to get the ferry back to Edgartown. I was unfamiliar with the road and turned right onto Dyke Road instead of bearing hard left on Main Street. After proceeding for approximately one half mile on Dyke Road, I descended a hill and came upon a narrow bridge. The car went off the side of the bridge. There was one passenger with me, one Miss Mary ________,* a former secretary of my brother, Senator Robert Kennedy. The car turned over and sank into the water and landed with the roof resting on the bottom. I attempted to open the door and the window of the car but have no recollection of how I got out or the car. I came to the surface and then repeatedly dove down to the car in an attempt to see if the passenger was still in the car. I was unsuccessful in the attempt. I was exhausted and in a state of shock. I recall walking back, to where my friends were eating. There was a car parked in front of the cottage, and I climbed into the back seat. I then asked for someone to bring me back to Edgartown. I remember walking around for a period of time and then going back to my hotel room. When I fully realized what had happened this morning, I immediately contacted the police.”

*Kennedy omitted the last name, unsure of the spelling.

The statement did not entirely satisfy Supervisor George W. Kennedy of the Massachusetts Registry of Motor Vehicles, which must investigate fatal automobile accidents. Upon reading it at the police station, he said to Kennedy, “I would like to know about something.”

“I have no comment,” the Senator replied.

The supervisor looked at Markham and Gargan. Later he testified: “They said to me that he would make a further statement later, and he would answer more questions.”

A Hail of Questions. Chief Arena, six-foot-four, 225 pounds, former high-school football star, Marine sergeant and state trooper, is an affable, guileless and honest small-town policeman who then was earning $10,500 a year. He was genuinely saddened by this, the latest tragedy to afflict the Kennedy family. So when Kennedy said he wished to contact his family lawyer, former Assistant Attorney General Burke Marshall, and promised to communicate with the chief later, Arena permitted him to depart without being interrogated. The Kennedy statement offered no hint that Markham and Gargan might know something about the accident. Thus it did not occur to Arena to seek information from them, and they volunteered none.

Markham implored Arena to withhold the statement from the press until after Kennedy consulted Marshall, and the request was repeated by telephone in the afternoon. But, besieged by demands from newsmen, Arena had already released the statement about 3 p.m. Far from mollifying the press, the statement precipitated a hail of questions.

Why had Kennedy not summoned help to rescue Miss Kopechne? Why had he waited ten hours to report the accident? Where had he been and what was he doing all that time? Why did he drive off the bridge? How? Which friends were “eating”? Where? Why didn’t “his friends” do something? Where did the investigation stand?

Overwhelmed by all these questions, Arena consoled himself with the thought that he could obtain the answers when next he talked to Kennedy. He did not know that he would never have that chance. Neither did he know that there were ten other people who could have supplied information but that all had vanished from the island.

Only one Kennedy representative remained on Martha’s Vineyard, K. Dunn Gifford, and he could provide no evidence. He had landed in a chartered plane early that afternoon with a single mission—remove the body as quickly as possible. At the funeral home he kept vigil, asking anxiously whether there would be an autopsy or a “hold.” There would be neither.

Miss Kopechne was buried July 22, 1969, in a country cemetery in Pennsylvania. Her parents, Mr. and Mrs. Joseph Kopechne, a proud couple of modest means, refused a Kennedy offer to pay the funeral expenses. To bury their daughter, they borrowed from a bank and withdrew savings they had put aside to pay someday for her wedding.

Grand Council. During the next six days, Kennedy sequestered himself in silence behind the gates of the family compound at Hyannis Port, Mass., leaving only to fly to Miss Kopechne’s funeral and right back. He and those closest to him recognized the crisis. Famous men assembled at the compound to counsel, devise strategy and help draft a second statement, since the first was now being widely questioned. Among those who traveled to the grand council were former Defense Secretary Robert McNamara; John Culver and John Tunney, then Congressmen and later Senators from Iowa and California; Theodore Sorensen and Richard Goodwin, speech-writers for the late President Kennedy; attorneys Burke Marshall and Milton Gwirtzman; Harvard Professor Arthur Schlesinger, Jr.; political adviser Kenneth O’Donnell; and family business manager Stephen Smith. Meanwhile, on Martha’s Vineyard, attorneys negotiated on behalf of Kennedy.

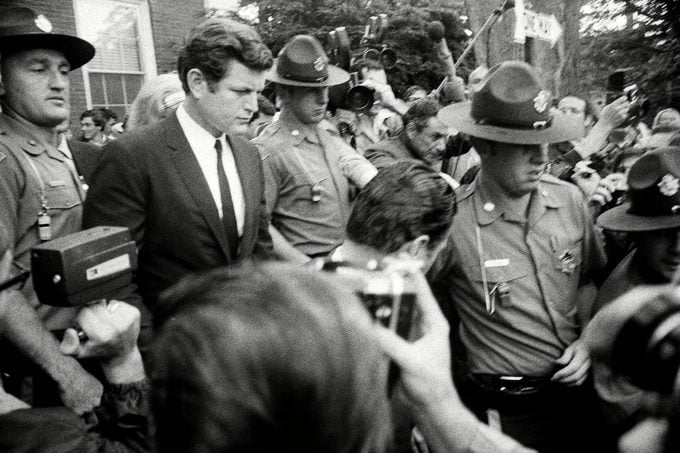

Their success enabled the Senator to break silence on July 25. Appropriate arrangements with the prosecution having been consummated, Kennedy returned to Edgartown and pleaded guilty to a misdemeanor charge of leaving the scene of an accident. The judge, with concurrence of the prosecution, imposed the minimum sentence law permitted—a two-month jail term, suspended, and revocation of driver’s license for a year.

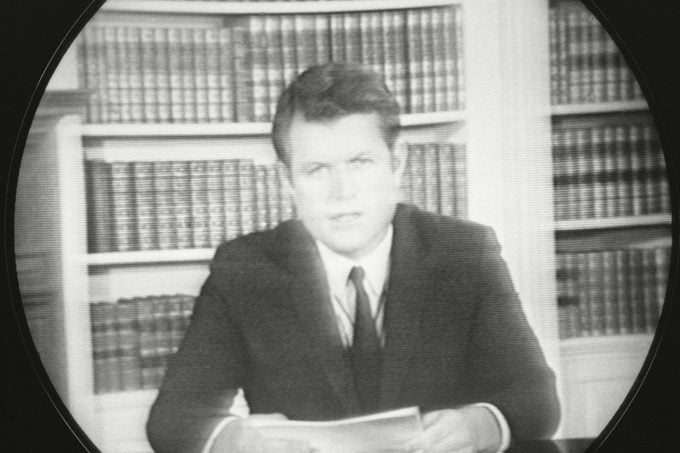

Announcing that ”tonight I am free to tell you what happened,” Kennedy that evening delivered “to the people of Massachusetts” (and to an avidly curious national audience) a 17-minute television address which differed significantly from the statement he had handed Chief Arena six days before. Six months later, in January 1970, Kennedy, Markham, Gargan and others testified under oath at a closed inquest into the death of Miss Kopechne.

What actually happened on that fateful night? The account of events as related piecemeal by the Senator and his friends, in the television speech and the inquest transcript (released on April 29, 1970), has not been altered by them in the decade since the accident. Here is a summation of their version, followed by an analysis of the critical questions it raises—and some new findings.

A Turn to the Right. For 30 years, Kennedys had sailed in the annual Edgartown Regatta. To uphold this tradition and also to attend a party he had “encouraged and helped sponsor for a group of devoted Kennedy campaign secretaries,” Kennedy arrived in Edgartown about 1 p.m. on July 18th. Chauffeured by 63-year-old factotum John B. Crimmins, he rode the ferry to Chappaquiddick to refresh himself with a swim in the Atlantic before the race. To reach the beach, they had to turn from the island’s only paved road, go down Dyke Road and cross the 10.5-foot-wide bridge over Poucha Pond. They had to come back the same way. [Thus, Kennedy twice traversed the extremely bumpy, jarring road and the distinctive bridge above the pond where Miss Kopechne was soon to die.]

Having finished ninth in his race, Kennedy checked in at the Shiretown Inn, dressed and had “perhaps a third of a beer” with friends before Crimmins drove him back to Chappaquiddick at 7:30 p.m. Ferry operator Jared Grant, who stayed on duty from 6 p.m. until 1:20 a.m., remembered: “It was a beautiful night, very calm, the water was like glass.”

For the party, Gargan had rented a two-bedroom house known as the Lawrence Cottage, which stands some 30 feet off the main, paved road leading to the ferry slip three miles away. Among the guests were six unmarried women, all in their 20s, Miss Kopechne at 28 being the oldest. Others present were Kennedy, Crimmins, Gargan, 39, Markham, 39, Tretter, 30, and Raymond LaRosa, 41, a Massachusetts civil defense official.

Crimmins had stocked the house with three half-gallon bottles of vodka, four fifths of scotch, two bottles of rum and two cases of beer. According to inquest testimony, during the entire evening nobody had more than three drinks, and Kennedy drank his last rum and Coca-Cola at 9 p.m. The friends entertained themselves by dining on steaks, singing, dancing, listening to the radio, reminiscing and walking.

At 11 p.m. Kennedy maintains, he decided to return to his hotel for a good night’s sleep. Miss Kopechne, who happened to be talking to him, indicated she also wanted to leave and asked if he would be kind enough to drop her off at The Dunes, the motel where she and the other women had rooms, which was several miles from his hotel. Obtaining the car keys from Crimmins, Kennedy drove away with her along the main road toward the ferry.

But instead of continuing on the paved road where it curves sharply leftward, Kennedy mistakenly turned right and proceeded down the bumpy, dirt Dyke Road at 20 miles an hour. Although he was “absolutely sober,” concentrating solely on the road ahead and undistracted by anything, he did not realize his error, nor did he see the bridge until “fractions of a second” before he was upon it. The black sedan hurtled off the right side of the bridge, turned over and sank until the top rested on the bottom of the pond.

Water surged into the car through the left front window, which was rolled down, and the two right windows, which were blown out by impact. “I remember thinking as the cold water rushed in around my head that I was, for certain, drowning. But somehow I struggled to the surface alive.” (In subsequent public comments, Kennedy never has been able to recall how he escaped from the car underwater. He does recall “the movement of Mary Jo next to me, the struggling, perhaps hitting or kicking me.”]

Upon surfacing, Kennedy “was swept away by the tide that was flowing at an extraordinary rate through that narrow cut” and “couldn’t swim at that time because of the current.” But having waded to the shore and regained his breath, he returned and dove seven or eight times toward the car, whose lights were still shining. The powerful current frustrated his rescue efforts, though, and after 15 to 20 minutes he was too exhausted to keep trying. So he rested on the bank 15 to 20 minutes, then commenced “walking, trotting, jogging, stumbling” back to the Lawrence Cottage.

[En route, Kennedy had to pass within a few feet of a lighted house on his left near the bridge and another lighted house a little farther on the right, each with a telephone. He also had to walk or trot within a few feet of a lighted, open fire station where, by pulling a well-marked alarm, he could have aroused the whole island.]

When he reached the cottage, Kennedy climbed into the back seat of a parked Valiant after calling to LaRosa, standing at the front door, to bring Gargan, then Markham. “The car has gone off the bridge down by the beach, and Mary Jo is in it.” As they raced toward the bridge about 12:20 a.m., Kennedy offered no details of the accident, nor did his friends ask for any.

“I Will Take Care of It.” Gargan drove across the bridge. With the Valiant’s lights shining over the pond they could see the overturned Oldsmobile. Markham and Gargan took off their clothes and during the next 45 minutes dove again and again, endeavoring to enter the sunken car. But they too were thwarted by powerful currents. Kennedy remembers that when Gargan pulled himself out of the pond, “he was scraped all the way from his elbow, underneath his arm was all bruised and bloodied.”

Abandoning the rescue attempts as futile, they drove toward the ferry slip with Kennedy sobbing and almost breaking down completely in tears. “This couldn’t have happened. I don’t know how it happened.”

“Well, it did happen, and it has happened,” Markham said.

“What am I going to do? What can I do?”

Sitting in the car at the ferry landing, they talked ten minutes or so, and Gargan urged Kennedy to telephone his family, administrative assistant David Burke and attorney Burke Marshall. “You have got to report this thing immediately.”

“All right, all right, I will take care of it. You go back, don’t upset the girls, don’t get them involved; I will take care of it.” With that, Kennedy got out of the car, took a few paces to the shore, “impulsively” jumped into the harbor channel and began swimming toward Edgartown.

“Now, I started to swim out into that tide, and the tide suddenly became..felt an extraordinary shove and almost pulling me down again, the water pulling me down, and suddenly I realized at that time even as I failed to realize before I dove into the water that I was in a weakened condition … the tide began to draw me out, and for the second time that evening I knew I was going to drown, and the strength continued to leave me. By this time, I was probably 50 yards off the shore, and I remembered being swept down toward the direction of the Edgartown Lighthouse and well out into the dark… And some time after, I think it was about the middle of the channel, a little further than that, the tide was much calmer, gentler, and I began to get my…make some progress, and finally was able to reach the other shore…”

Kennedy struggled toward the Shiretown Inn, “leaning against a tree for a length of time to recover his strength. Sometime before 2 a.m. he shed his wet clothes and “collapsed onto the bed.” His head throbbed, his neck and back hurt, and he was “conscious” of “the tragedy and loss of a very devoted friend.” Because he “wasn’t sure whether it was morning or afternoon or nighttime,” he put on dry clothes, went downstairs and asked an innkeeper what time it was. It was 2:25 a.m.

“I Didn’t Report It.” Back on Chappaquiddick, Gargan and Markham, according to their sworn testimony, had watched from the shore until Kennedy swam half or three quarters of the way across the harbor channel. Satisfied that he was safe and would report the accident as promised, they drove around for a while and returned to Lawrence Cottage between 2 and 2:15 a.m.

There they conveyed the impression that all was well. Gargan told some of Miss Kopechne’s friends that she had driven the Oldsmobile to Edgartown alone on the last ferry and was in her motel. After they failed to find a boat for the Senator, he elected to swim back to his inn. Instinctively, they dived into the channel after him but then decided to let him swim on home by himself.

When this scene was recreated during testimony at the inquest, the presiding judge, James A. Boyle, became curious. As one of the Kennedy campaign workers, Maryellen Lyons, recounted under oath what Gargan and Markham said, Judge Boyle interjected:

“Didn’t you say to them, ‘Well, how come Mary Jo takes the car and the Senator swims?”

“I just assumed that…,” Miss Lyons started to reply.

“Didn’t you have some thoughts in your mind that this was most peculiar?”

“Not really. As I say, it didn’t ‘t come out quite that way.”

“You knew they left together in a car?”

“Yes.

“And then you presumed to Edgartown?”

“No. I didn’t know where they were going. Nobody had said anything to me when they left.”

“Then you learned that the Senator had to swim because there were no boats, that the car, his car in which be had left with Mary Jo, had traveled across that ferry with Mary Jo?”

“Well, I just assumed that for some reason he decided he didn’t want to.”

“Nothing struck you as unusual about that?”

“No, not really, Your Honor.”

In the morning, after finding Kennedy chatting with Richards on the porch, then going with him to his room, Gargan and Markham asked, “What happened?”

“I didn’t report it,” Kennedy said. During the night, he had “tossed and turned, paced that room,” unable to “gain the strength within me, the moral strength to call Mrs. Kopechne.” He “somehow believed that when the sun came up and it was a new morning that what had happened the night before would not have happened and did not happen…it was just a nightmare. I was not even sure it happened.”

“Well, it happened, and you have got to report this thing, and you have got to do it now,” Markham said. Gargan then insisted that Kennedy telephone Burke Marshall and David Burke at once. As Kennedy desired privacy in making the calls, Gargan suggested the phone at the ferry landing on Chappaquiddick. Hence, they rode the ferry over to Chappaquiddick to use the phone at the landing where Kennedy began his swim the night before.

That is what Kennedy and his friends swore happened. And that is what Kennedy today claims happened.

The family physician who examined him on July 19 stated that the Senator had sustained “a slight concussion” and that “irrational behavior is not inconsistent with such a condition.” However, in his television speech, Kennedy said,”…I do not seek to escape responsibility for my actions by placing the blame either on the physical and emotional trauma brought on by the accident or on anyone else.” And subsequently he acknowledged that, in any case, by early morning when he visited with Richards he was “completely in control of my senses.”

Kennedy stated that his actions, as he recounted them, “make no sense to me at all”; that his failure to report the accident immediately is “indefensible”; that his various words and deeds were “inexplicable, inconsistent and inconclusive.” He told the television audience, “I was overcome, I’m frank to say, by a jumble of emotions: grief, fear, doubt, exhaustion, panic, confusion and shock.”

Eight Basic Questions. Because Kennedy’s ultimate explanation is that his conduct defies explanation, it is perhaps not surprising that the record remains littered with implausibilities and outright contradictions—and raises doubts that Kennedy is telling the truth. These eight basic questions in particular leap from the available evidence:

Where was Kennedy actually taking Miss Kopechne?

This question occurred to Judge Boyle because of a variety of facts adduced at the inquest. Kennedy told no one except Crimmins that he and Miss Kopechne were leaving the party and, though he was the host, he said goodnight to none of his guests. Although he ostensibly was departing to be sure of crossing before the last scheduled ferry run at midnight, and although eight of the remaining guests planned to return to Edgartown for the night, he offered none of them a ride.

Kennedy on this one occasion chose to drive himself, although he rarely drove on any other. Crimmins testified that when Kennedy asked him for the car keys, he explained that he was taking Miss Kopechne to Edgartown because she was ill. Yet Miss Kopechne told no one that she was ill, not even Kennedy, as he subsequently has admitted. She said good night to none of her friends. Although she did not have a key to her motel room, she did not ask her roommate for a key, and she did not trouble to take her purse with her.

The greatest difficulty with Kennedy’s claim that he was headed for the ferry, however, arises from the nature of the roads he traveled. To go from the paved main road leading to the ferry onto the dirt Dyke Road, a driver must consciously slow to a near halt and execute a 90-degree turn. A driver instantly feels the difference in the surfaces. The main road is smooth macadam; Dyke Road is, as countless investigators have said, like a “washboard.” Kennedy contends that “the difference between paved and unpaved, for anyone who lives on Cape Cod or visits the island… the roads are indistinguishable.” But Washington Star reporter James R. Dickenson summed up the conclusion reached by numerous other journalists over the years when he wrote last November: “However, his contention that he inadvertently took a wrong turn and that he thought he was headed west on the asphalt road to the ferry to Edgartown instead of the dirt road east to Dyke Bridge and the Atlantic beach is, to anyone who has driven it, not just inexplicable—it’s incredible. That is the best interpretation that can be put on it.”

To Judge Boyle, Kennedy’s claim also was incredible. During the inquest, the judge was far from hostile to the Senator and, indeed, at times precluded questions or testimony that might have been damaging. Nevertheless, in his final findings, Judge Boyle stated:

“I infer a reasonable and probable explanation of the totality of the above facts is that Kennedy and Kopcchne did not intend to return to Edgartown at that time; that Kennedy did not intend to drive to the ferry slip, and his turn onto Dyke Road was intentional…

A speed of even 20 miles per hour, as Kennedy testified to, operating a car as large as this Oldsmobile would at least be negligent and, possibly, reckless. If Kennedy knew of this hazard, his operation of the vehicle constituted criminal conduct.

Earlier on July 18, he had been driven over Chappaquiddick [Main] Road three times and over Dyke Road and Dyke Bridge twice. Kopechne had been driven over Chappaquiddick Road five times and over Dyke Road and Dyke Bridge twice.

I believe it probable that Kennedy knew of the hazard that lay ahead of him on Dyke Road but that, for some reason not apparent from the testimony, he failed to exercise due care as he approached the bridge.

I therefore find there is probable cause to believe that Edward M. Kennedy operated his motor vehicle negligently on a way or in a place to which the public have a right of access and that such operation appears to have contributed to the death of Mary Jo Kopechne.”

Did the accident happen the way Kennedy explains it?

In the four decades that Dyke Bridge has stood over Poucha Pond, Kennedy is the only person ever to drive off it.

Five of Kennedy’s friends who were at the party swore that both he and Miss Kopechne appeared perfectly sober when they left. Because the Senator did not go to the police until many hours after the accident, he was not given blood or Breathalyzer tests. So there is no proof that he was not “absolutely sober,” as he says.

Yet the manner in which he drove down Dyke Road was not that of a responsible man in control of himself. Kennedy testified at the inquest that he did not realize he had turned onto the wrong road until almost the moment he plunged into the water. Yet, also at the inquest, Markham quoted him as saying that “he took the wrong turn and he couldn’t turn around.” In fact, there were several places where he could have turned around, including two driveways within 150 yards of the bridge.

Kennedy also swore that, although looking straight ahead, he did not see the bridge until ”fractions of a second” or “the split second” before driving onto it. But when Markham returned with Kennedy and Gargan later that night “going fast,” Markham could see the bridge ahead. An Arthur D. Little Co. study, ordered by Kennedy, reported that it was “essentially impossible to see the roadway over the bridge at night at a distance of much greater than between 60 feet to 90 feet.” The most authoritative data show that at 20 mph, a reasonably attentive driver can react and halt a car on dry gravel within at least 6o feet. So even under the most adverse conditions cited by his own study, Kennedy still had time to spot the bridge and completely stop—if, as the Senator swore and his consultants assume, he was going only 20 mph.

Heretofore, the Senator’s estimate of his speed has not been challenged, probably because it seemed to be corroborated by the testimony of Supervisor Kennedy. From skid marks “starting at the edge of the bridge on the dirt,” the Motor Vehicles Registry investigator calculated the speed at 20 to 22 mph. But it is impossible scientifically to deduce speed solely on the basis of skid marks suddenly interrupted—as were those left by the Oldsmobile when it vaulted off the bridge. No one at the inquest asked Supervisor Kennedy about this technical fact. And the judge stringently prohibited him from testifying about the possibility that the skid might have started much farther down the road, where by next morning traffic would have obliterated traces.

Supervisor Kennedy now is dead. The Massachusetts Registry of Motor Vehicles last October refused to release a copy of his original accident report without written notarized authorization from Senator Kennedy himself.

How fast was Kennedy traveling? To find out, Reader’s Digest consulted traffic engineers with long experience in evaluating accidents for both the federal government and private clients. The evidence, particularly relating to the trajectory and distance the car sailed from the bridge, convinced them that Kennedy must have been driving much faster than 20 mph.

Reader’s Digest then commissioned an elaborate scientific study by Raymond R. McHenry, one of the nation’s foremost experts in automobile-accident analysis. Utilizing sophisticated analytical techniques, validated by the Department of Transportation and accepted in numerous legal cases, McHenry fed masses of data—including the weight and wheelbase of the car, the elevation of the road, and the geometric features of the bridge—into an IBM computer. After repeated computer runs, he mathematically re-created the movements of the car. Here are what his final calculations reveal:

• Driving on the wrong (left) side of the road, Kennedy approached the bridge at approximately 34 mph. (Abiding by rigorous scientific standards, McHenry stipulates that his speed computations could be an error by plus or minus 4 mph. Thus the car was traveling at a minimum outside of 30 mph; it could have been going as fast as 38 mph.

• Kennedy saw the bridge when he was at least 50 feet away from it, probably from farther away. At least 17 feet from the bridge, he slammed the brakes down hard—”panic braking, “which locked the front wheels. Propelled by the high speed, the car skidded 17 feet along the road, about another 25 feet up the bridge; jumped a 5½-inch-high rub rail and hurtled approximately 35 more feet into the water. Despite Kennedy’s braking effort, the car was still traveling between 22 mph and 28 mph when it shot out over the pond.

Judge Boyle ruled that to travel the jarring Dyke Road even at a speed of 20 mph was “negligent and possibly reckless.” By approaching the hazardous bridge at 30 to 38 mph, Kennedy clearly invited the disaster that in fact ensued.

Did Kennedy and or Markham and Gargan actually attempt to rescue Miss Kopechne as they claim?

There were no witnesses to the diving efforts Kennedy says he made. By his account, an “extraordinary” current was the primary reason he failed.

To ascertain just how strong a current he would have encountered, Reader’s Digest last November commissioned a scientific study by Bernard LeMehaute, an internationally renowned oceanographic engineer. His assistant, Ernest Daddio, sampled the current at Poucha Pond throughout the day of November 9, when tidal conditions were nearly the same as they were the night of July 18-19, 1969. Scrupulously following scientific methodology of proven reliability, LeMehaute determined that at the time Kennedy says the accident occurred, the current was flowing at approximately 8 knots in the center of the pond, 1.2 knots at the eastern edge and probably one knot in the area where the car sank. In the opinion of Navy divers and civilian water-safety experts consulted by Reader’s Digest, a current of between .8 and 1.2 knots would constitute a significant impediment to someone trying to swim any appreciable distance against it, especially with clothes on. However, given the prevailing conditions, water-safety experts believe that such a current would not have posed an insurmountable obstacle to a poised and experienced swimmer determined to rescue someone.

The car settled less than ten yards from shore, its location conspicuously marked by headlights still shining under water. Tidal data indicate that the maximum depth of the pond at the time was less than seven feet. By stepping into the water a short distance downstream, a rescuer could have waded part of the way from the shore, then swum the few remaining yards with the current at his back. Upon grabbing the undercarriage of the overturned car he would have had to pull himself down only four feet or so to enter or reach into the passenger compartment through one of the three open windows.

“That’s the way it could have been done, and the way it should have been done,” says Bernard Empleton, executive director of the Council for National Cooperation in Aquatics.

Gargan and Markhan also cite the ferocity of the current as a principal cause of their failure to reach Miss Kopechne. By 12:20 a.m., when they supposedly began their dives, the current had increased to 1.3 knots in the middle of the pond and 1.5 knots on the eastern side. Again, in the judgment of expert divers, currents of such velocity would make rescue efforts more difficult but not impossible.

At the inquest, some of Kennedy’s friends were asked whether they noted any injuries to Gargan and Markham when they returned. All said no. In the Edgartown police station the next day, Gargan wore a short-sleeved shirt. Yet neither Arena nor Supervisor Kennedy observed any injury to either of his arms, one of which, according to the Senator, had been “scraped all the way from his elbow … all bruised and bloodied.”

After 9 a.m. on the 19th, Gargan went back to Lawrence Cottage and finally informed some of Miss Kopechne’s friends that there had been an accident and she was missing. “What was done to help her?” the women asked. “Was the Coast Guard called?”

“I don’t know,” solemnly replied lawyer Gargan, who only a few hours earlier allegedly had repeatedly risked his life to save Miss Kopechne.

Not until a week later, after public criticism of his failure to do more for Miss Kopechne mounted, did Kennedy come forth with the story that he had enlisted Gargan and Markham in a rescue expedition.

Why did Kennedy and his friends not summon help immediately?

Less than three minutes after wading to the shore, Kennedy could have had professional help on the way simply by walking to the lighted house some 400 feet from the bridge. Its occupants, the Pierre Malm family, would have made the calls, and Kennedy would not have wasted time trotting to the cottage (15 minutes by his estimate; 25 minutes according to reporters who later walked or jogged the route).

Gargan and Markham had experienced no trauma, and Gargan had drunk only about four Cokes because he especially wanted to be clearheaded to cook the steaks. En route to the pond, they could have paused a minute to sound the alarm at the fire station or call from one of the houses. They did not.

District Attorney Edmund Dinis explicitly asked Kennedy why he did not summon outside help after the accident. Requesting and receiving “the court’s indulgence,” Kennedy responded with a meandering monologue during which he retold the story of his harrowing swim across the channel and recounted his confused thoughts. But he did not answer the question. Minutes later, as the district attorney started to press Kennedy on his delay in reporting to the police, Judge Boyle recessed the inquest for lunch. Afterward, the question was not put again.

Toward the end of his testimony, Kennedy did state that after Gargan and Markham were unable to rescue Miss Kopechne, he was convinced that she was dead, and that therefore it was useless to summon help. However, during the remainder of the evening Kennedy, by his own account, hoped she was alive and acted as if she might be alive.

Regardless, that was not the question. The question was and is: why was assistance not requested soon after the accident at a time when it conceivably could have meant the difference between life and death? Neither Kennedy nor Markham nor Gargan has ever been compelled to answer that question.

Could Miss Kopechne have been saved?

The Arthur D. Little Co. study made for Kennedy concluded that water would have rushed into the car and expelled air from it so quickly that Miss Kopechne could have remained conscious for only one to four minutes. She could have been revived up to ten minutes after she lost consciousness, the study reported. So, according to the analysis made under his auspices, Kennedy could have saved Miss Kopechne had his first efforts succeeded.

The telephone rang at diver Farrar’s Turf and Tackle Shop at 8:25 a.m. on the 19th, and he removed the body from the car at 8:55 a.m. He was delayed five minutes at the ferry landing because the ferry had just departed. Thus, it is reasonable to assume that, had he been summoned after the accident, Farrar could have retrieved Miss Kopechne within 30 minutes, possibly 25. That would not have been soon enough if the Arthur D. Little Co. study is correct.

However, Farrar, who was in the pond when the Oldsmobile was righted, says that large air bubbles emanated from the car then and as it was dragged out of the water. Both he and Jon Ahlbum, who supervised the removal of the car, state that there was no significant amount of water in its trunk. And the position in which Farrar found Miss Kopechne’s body strongly indicates that for an indeterminate time before death she breathed in an air pocket.

Associate Medical Examiner Donald R. Mills, who is a respected physician but not a pathologist, concluded after a ten-minute examination, during which he did not completely disrobe the body or look at all parts of it, that Miss Kopechne drowned. However, mortician Eugene Frieh, upon applying standard procedures to empty water from a drowning victim, was surprised that the body emitted “very little moisture.” He told reporters the paucity of water indicated that “death was due to suffocation rather than drowning.” Because the body was so buoyant, Farrar also is persuaded she did not drown.

Only an autopsy—never performed—could have established the cause and time of death with certainty. There is, though, one certainty. Whatever chance Miss Kopechne may have had to live was forfeited by Kennedy’s failure to call those competent to save her.

Is Kennedy telling the truth about his swim across the harbor channel?

The most recent scientific findings show that he is not.

Of all the episodes Kennedy has narrated, the channel swim is among the most melodramatic. He knew again that he was “going to drown.” Three times he mentions the ferocious tide that almost pulled him down and swept him northward “toward the direction of the Edgartown Light and well out into the darkness” as his strength ebbed perilously.

Storms and shifting sands have changed the topography of Edgartown harbor in the years since 1969. So it is impossible today to take measurements in the channel that would scientifically ascertain the precise velocity of the current between 1:35 and 1:45 a.m., July 19, 1969, the time Kennedy and his friends claim he made his swim. But other data, including tidal elevation differences, did enable Bernard LeMehaute to calculate the relative strength and direction of the current. “Around 1:30 a.m., the current was weak to zero,” he reports. “After about 1:30 a.m., the current flowed southward toward Katama Bay at an increasing velocity until approximately 4 a.m.” Thus, had Kennedy encountered any current at all, it would have swept him not northward toward the lighthouse, as he says, but southward, in exactly the opposite direction.

Furthermore, an analysis of the inquest transcript discloses that Kennedy’s account of his swim is contradicted by the separate, sworn testimony of his two loyal allies, Gargan and Markham.

From the ferry landing on Chappaquiddick, they watched three or four minutes until Kennedy was half to three-quarters of the way across the channel—well past the area where he claims the awful tides beset him. He was not being swept away. On the contrary, Markham testified that he was swimming toward the landing at Edgartown. Neither Markham nor Gargan observed him experiencing any difficulty; neither saw any cause for alarm.

“Weren’t you concerned about his ability to make it?” Judge Boyle asked.

“No, not at all,” Gargan replied. “The Senator can swim that five or six times both ways.”

Why’d Kennedy wait ten hours to report the accident?

To this question, Kennedy several times has replied by saying that he simply could not bear to call Mrs. Kopechne in the middle of the night. The question, though, is why did he not notify the police?

Asked by Boston Globe reporters in 1974, Kennedy said that while swimming the channel he thought to himself, I just can’t do it. I just can’t do it. I just can’t do it.

By 7:30 a.m., he was sufficiently composed to dress neatly, take a walk and talk with Richards casually about the weather. Why did he not go to the police then? Because, Kennedy says, he still hoped that the accident had not occurred and that Miss Kopechne was alive. That is what he “willed.”

Markham says that he and Gargan assured Kennedy that the accident had indeed occurred and advised that he must report it at once. But the Senator and his two friends did not report it then by walking a few blocks to the police station. Instead, they rode the ferry back to Chappaquiddick and stood around until suddenly confronted with evidence that the car had been discovered in the pond. Only then did they hurry to report the accident.

In its series of articles about Chappaquiddick, The Boston Globe on October 29, 1974, reported:

Further, a highly knowledgeable source has told the Globe that Kennedy’s own narrative contains significant inaccuracies, and a true account would contradict material elements of his public statements and sworn testimony at the inquest into Miss Kopechne’s death.

In particular, Kennedy’s cousin Joseph Gargan agreed at one point to take responsibility for the accident, the source said, but that plan was abandoned shortly before Kennedy reported the mishap to police.

The source, who was not associated with prosecutors of the automobile charge against Kennedy, vigorously disputed other aspects of Kennedy’s account, including a purported rescue attempt an hour after the accident.”

Uncorroborated statements by an unidentified source who does not feel at liberty to speak and be interrogated openly obviously do not constitute proof of anything. But the three reporters who prepared the Globe series are reputable journalists, and in other respects that Reader’s Digest researchers could check, their articles were accurate.

Was there a cover-up?

Kennedy contends that from the outset he fully and honestly has answered all questions about Chappaquiddick and that he will continue to do so. People who have doubts, he says, can look at the public record and judge for themselves.

Yet the inquest record of what Kennedy said to Markham and Gargan minutes before reporting to the police—”As far as you know, you didn’t know anything about the accident that night”—clearly demonstrates that, at least in the beginning, he intended to tell the authorities less than the complete truth.

And the carefully crafted report to Chief Arena did hide the fact that there were ten witnesses to events preceding and following the accident, two of whom possessed detailed knowledge. By omitting these facts, Kennedy enabled all the witnesses to leave the island before nightfall on July 19th, and avoid interrogation at a time when their memories were fresh and before they could be coached.

When a state official, Supervisor Kennedy, in pursuit of his duty, sought to question him, the Senator replied tersely, “I have no comment,” and walked away. He never made himself available to Chief Arena as he had promised, or to Supervisor Kennedy, as his friends had promised.

Contrary to the impression he has promulgated, Kennedy never submitted to examination or cross-examination in open court. His lawyers successfully bargained with the local prosecutor, Walter E. Steele, who, rather than prosecute Kennedy on the more serious charge of negligence, allowed him to plead guilty to a misdemeanor in return for a suspended sentence. Kennedy thus avoided the kind of searching, adversary interrogation a trial would have entailed.

“No matter how you cut it,” Steele later said, “you simply don’t treat a United States Senator who is a criminal defendant the same way you treat a stockbroker. It’s just one of the failings of human nature.”

Responding to public clamor and criticism, District Attorney Dinis requested an inquest and Judge Boyle scheduled one for September 3, stipulating that it would be open to the press. Kennedy lawyers then appealed to the Massachusetts Supreme Court, which on September 2 postponed the inquest indefinitely.

None of the young women at the party were ever suspected of wrongdoing. But Kennedy spent “something less than $32,000” of his own money to pay lawyers for them as well as for Crimmins, La Rosa and Tretter. These lawyers and his own filed suits demanding that the State Supreme Court order the inquest closed to the press and public, and the court ultimately obliged.

The inquest finally began on January 5, 1970. Its conduct in secrecy had significant effects. Had reporters been present to describe the glaring gaps and contradictions that the collective testimony yields, then public pressure for a serious investigation probably would have been irresistible.

Barred from the inquest, the press found little to report other than Kennedy’s confident assertion: “I expect to be vindicated and vindicated fully when the transcripts are made public and I am then allowed to answer questions.” But the transcripts were not soon to be made public, for the State Supreme Court ordered them withheld until any possibility of further legal action against Kennedy had passed.

The Dukes County grand jury had been eager to investigate the death of Miss Kopechne, but agreed to wait until after the inquest, persuaded that the transcript would facilitate its inquiry. In March 1970, foreman Leslie H. Leland, an idealistic young druggist, formally asked District Attorney Dinis to convene the grand jury in special session. “Everyone feels that a great injustice has been done to the democratic process, that there’s been a whitewash, a cover-up, and that things have been swept under the rug,” he declared. “I just feel we have certain duties and responsibilities as jury members to fulfill. A great deal of time has passed since the girl died, and it’s time the public found out what happened.”

Presiding over the special session was 67-year-old Judge Wilfred J. Paquet, a Democratic Party stalwart. As he harangued the jurors for 90 minutes about the limitations of their responsibilities, Paquet had sitting beside him a priest who, before the deliberations, had prayed that the jury would exercise “justice and charity.” The aging judge warned the jurors that they could consider only information provided by the court or Dinis, or information of which they had personal knowledge. To their astonishment, they were not allowed to read the inquest transcript or Judge Boyle’s findings (in which the judge concluded that Kennedy probably was guilty of “criminal conduct”).

Hamstrung by these restrictions, and given little data by Dinis, the jury could do nothing. They soon disbanded in frustration without returning an indictment. Kennedy was free.

On April 29, 1970, the inquest testimony was released. Later that day, Kennedy issued a statement: “In my personal view, the inference and ultimate finding of the judge’s report are not justified and I reject them. The facts of this incident are now fully public, and eventual judgment and understanding rests where it belongs. For myself, I plan no further statement on this tragic matter.”

“That’s the Way It Was.” For years, Kennedy and the ten others who were on the island with him have maintained a stonewall of silence around the mystery of Chappaquiddick. “I see no prospect of talking about it. Not today, not tomorrow, and not the next day. I see no necessity of talking about it ever,” said Markham. Gargan, Tretter and Crimmins, along with four of the women, have also remained mute.

ln 1974, Boston Globe reporters did elicit a few words from the fifth woman, Miss Esther Newberg: “… these are questions that should have been asked at the inquest and were not. [The answers] could result in national stories and I’m not about to subject myself to that kind of publicity again…Like everyone else, I’m mystified as to what went on. I can’t believe everything that’s been said in his [Kennedy’s] favor. There are so many conflicts.”

Ray LaRosa also said a few words: “The lawyers coached us pretty good. We knew what to expect.”

Last fall, with the approach of his entry into the Presidential campaign, Kennedy began to grant a few interviews. But he has yet to deviate from the story he told some ten years ago. In a CBS telecast last November, correspondent Roger Mudd asked, “Do you think, Senator, that anybody really will ever fully believe your explanation of the Chappaquiddick…?”

The reply of Senator Kennedy, verbatim, was:

“Oh, there’s…the problem is…from that night…I found the…the…the…the…conduct and behavior almost as sort of…beyond belief myself.

That’s why it’s been…but I think that that’s, that’s the way it was.

That’s, that’s, that happens to be the way it was.

Now…I find it as I’ve stated, that…I’ve found that the conduct, that…that evening, in, in, in, in the…as a result of the impact, of the accident, and the…and the the sense of loss, the sense of hope, and the, and the sense of tragedy and the whole set of certain circumstances, that…the, the behavior was inexplicable.

So I find that those, those…those types of questions as they apply to that…they’re questions in my own…soul, as well.

But, that, that happens to be the way it was.”

Shortly after offering this explanation, Senator Kennedy declared on NBC’s “Meet the Press”: “There is not going to be any new information that is going to challenge my testimony…if there was ever going to be any new information that was going to be different or challenge the sworn testimony that l gave, there would be absolutely no reason that I should consider either, one, remaining in public life, let alone run for the Presidency of the United States. Absolutely none.”

Recent scientific findings by oceanographic engineer Bernard LeMehaute show that the main part of Kennedy’s sworn account of his swim across the Edgartown harbor channel is false. Recent scientific findings by the eminent accident analyst Raymond McHenry show that Kennedy’s sworn account of how he drove down Dyke Road is false. Thorough analysis of the inquest testimony shows that Kennedy’s often repeated claim that he cooperated wholeheartedly with investigators is false.

Despite all this “new information,” Senator Kennedy adheres to his ten-year-old story and insists: “‘that happens to be the way it was.” So now, as Senator Kennedy himself states: “People will have to form their opinions.”