Goosebumps

On cold mornings, my guinea pig Chester looks like a big white fluff ball because his fur is standing up, creating a layer of insulation around his body. Most mammals can do this, and our ancestors also had the ability, plus the full-body coat that made it useful. Modern humans have lost their thick layer of body hair (maybe our ancestors needed to be able to release body heat on the savannas, or maybe hairless skin allowed them to avoid some dangerous parasites), but we retained the tendency for tiny muscles in our skin to contract when we feel chilly or scared, like a cat facing off with a dog.

Tailbone

Humans and our closest relatives, the great apes (chimpanzees, bonobos, gorillas, and orangutans), all have a collection of just a few vertebrae at the bottoms of our spines called a coccyx. It’s a remnant of what in many other mammals grows out to become a tail for wagging (dogs), grabbing tree limbs (monkeys), or balancing on top of fences (squirrels). Tails actually go all the way back to our earliest vertebrate ancestors, which is why fish, reptiles, and birds all have them as well. Because no members of what we consider early human species had tails, researchers speculate that they might have gotten in the way when our ancestors began walking upright, according to LiveScience, but we never lost the trait completely: Human embryos briefly develop tails at around four weeks of gestation.

Wisdom teeth

Early humans had bigger jaws than we do, with plenty of space for the third set of molars on top and bottom. We’ve since evolved brains that take up more space in our heads, so those teeth don’t always fit in our diminished mouths—they develop inside the gums but, without space to emerge, they can cause pain and infections and are frequently extracted. These are some of the unsolved mysteries of the human body.

Appendix

This is another evolutionary leftover that not only isn’t obviously useful but actually causes problems when it gets infected. Charles Darwin cited the appendix—a small structure near the beginning of the large intestine—as an example of a vestigial digestive organ, which he and his contemporaries figured had been rendered useless in apes and humans when we switched from eating grass to mostly fruit. However, in recent years, scientists have realized that many other mammals have appendices (including koalas and beavers). The tiny organ might be part of the immune system, according to Scientific American, assisting the body’s defenses by storing healthy gut bacteria.

Semilunar fold in the eye

Many mammals and some birds, reptiles, and sharks have an extra eyelid called the nictitating membrane; it’s semi-transparent and swipes across the eye from the inside corner. This extra eyelid helps protect the eye from debris or injuries and typically also helps keep the cornea moist. In humans and most other primates, though, the third eyelid has been reduced to a fleshy fold in the corner of the eye, without any purpose. This might have happened because we use hands to grab food, rather than attacking prey with our mouths and digging around in fields with our faces, so we evolved to need less protection around our eyes. Did you know that the eye, specifically the iris, is one of the body parts as unique as a fingerprint?

Ear muscles

One of my childhood best friends could wiggle her ears, but the trick’s only use was to entertain fellow grade-schoolers, as far as I could tell. We all have tiny muscles around our ears that are weak, ineffective versions of the ones that would have helped our evolutionary ancestors turn their ears in the direction of a sound, the way a rabbit does. When we hear an unexpected sound behind us, the muscles still twitch around the ear closest to the noise.

Palmaris longus tendon

The modern human body has a number of other muscles and tendons that are left over from evolution and no longer serve a specific or necessary function. The palmaris longus is a tendon on the palm side of the wrist that is absent completely in about 16 percent of people; for the rest of us, it’s isn’t necessary and can be cut without causing any problems. It’s actually really useful, though, for people who need tendon grafts in other places—surgeons can remove it and put it where it will do more good. Here are more body parts you didn’t know you had.

Plantaris

This muscle is at the top of the lower leg in the 90 percent of people who have it. It does help flex the knee, but only a little bit—people who don’t have one don’t miss it. The tendon that connects to the plantaris muscle is actually the longest one in the body, so like the palmaris longus tendon in the arm, it can prove very useful to someone who needs tendon tissue replaced elsewhere.

Pyramidalis and sternalis

These two muscles are so unnecessary that lots of people don’t have them at all, and nobody would be able to tell the difference without a surgical inspection or special imaging. The pyramidalis is in the abdomen (20 percent of people don’t have it), and the sternalis is a tiny muscle that runs over the top of the pectoral muscles in only about 8 percent of the population.

Whisker muscles

Almost all mammals have whiskers, except for anteaters, platypuses, and us. Whiskers are generally super-sensitive to a variety of stimuli and can tell the animal a lot about its environment, even in the dark—a seal that’s blindfolded and wearing headphones can still catch a fish using the information it gets through its whiskers. Humans have evolved to collect input through other senses, but we still have tiny vestigial muscles in our upper lips that would at some point in our evolutionary past have controlled whiskers. Her are more biological reasons behind some of our wackiest body parts.

Nipples on men

These aren’t exactly a remnant of evolution over generations, but they do highlight the way the human body develops. During the first several weeks of gestation, male and female embryos grow pretty much in exactly the same patterns. Around week six or seven, genes on the Y chromosome cause male embryos to develop testes, which then—around week 9—begin producing testosterone that triggers male characteristics to develop. By then, nipples have already formed, and they stick.

Hiccups

During a hiccup, the muscles we use to inhale contract while the vocal cords are slammed shut at the same time by the tongue and the roof of the mouth. There’s no discernible purpose for hiccups in humans, but a similar pattern of movement among amphibians is useful—when they’re breathing underwater during a stage at which they have both lungs and gills, tadpoles take in a mouthful of water, close the opening to the lungs, and then force the water out through their gills. In both humans and amphibians, the signal initiating hiccup-like activity comes from the brain stem, so scientists suggest our hiccups might be a holdover from fishy ancestors. Don’t miss these incredible things our bodies are doing every minute.

Palmar grasp reflex

Newborn humans are fragile and helpless, but they have a surprisingly strong hand grip that is likely left over from a time when they needed to be able to grab hold of their (hairy) parents to be carried around. Nowadays, many babies can hold on tightly enough to support their own weight. The reflex lasts for about the first four months of life, and is noticeable in infants’ feet as well.

The ability to drink milk

Some human traits have evolved much more recently in our species’ history, as a result of lifestyle and cultural factors. Before 10,000 years ago, only babies produced lactase, the enzyme required to allow us to digest milk. But when humans started raising cattle and camels in Northern Europe, East Africa, and the Middle East, people with the genetic variation allowing them to keep making lactase into adulthood had a nutritional advantage and passed their genes along. Today, more than 90 percent of humans can drink milk. Here are more fascinating things you had no idea your body accomplished today.

Blue eyes

All humans had brown eyes until 6,000 to 10,000 years ago, when a genetic mutation produced the entirely new eye color. There’s no obvious evolutionary advantage to blue eyes, but they’ve persisted anyway; about one in six Americans has blue eyes now. That’s actually down from around half of Americans born at the turn of the 20th century who had blue eyes. Researchers suggest that fewer people marry within their own ethnic group now, as they did routinely 100 years ago, enabling the recessive trait of blue eyes to get passed along.

Have you ever wondered if people with blue eyes are related? Here’s the answer.

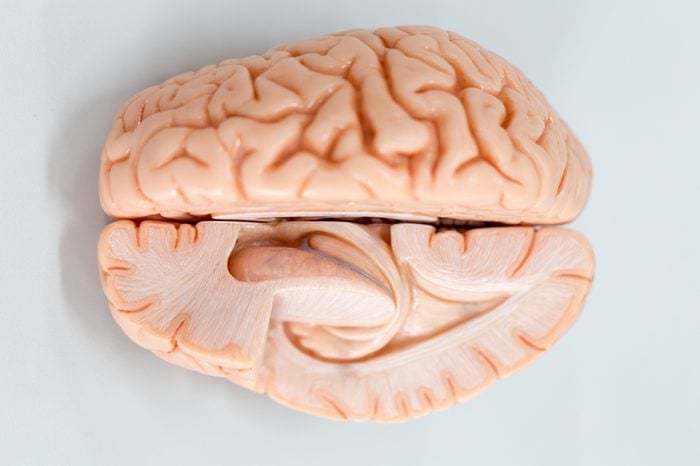

Changing brains

Over the past 20,000 years or so, human brains have actually been shrinking, according to researchers. University of Wisconsin anthropologist John Hawks told Discover Magazine that it has happened in Asia, Europe, Africa—”everywhere we look.” We might be getting dumber, or we might just be getting more efficient. Either way, we’re also changing our brains with our daily activities: Though we’re not rewiring neurons in ways that will be passed down genetically, modern smartphone-using humans do show different types of connections between their brains and their thumbs than those who haven’t been surfing Facebook on little screens. Next, make sure you know these myths about the human body that could seriously damage your health.