It’s not just dinos

Dinos might get most of the glory in museums and on screen, but “when dinosaurs roamed the Earth” is still a bit of a blip compared to the entire time the planet has been around. There are scores more gigantic, toothy, and winged creatures that existed way back when that are straight-up terrifying. Let’s take a look at some monstrous beasts, birds, and bugs that’ll make you relieved you didn’t live back then. By the way, here are some things that would happen if T. Rex and friends were still around today.

Saber-toothed cat

The Smilodon lived in North America until around 13,000 years ago, which means it probably overlapped with early human inhabitants. “Saber-toothed cats were not only hypercarnivores with six-inch-long fangs, but evidence from our site indicates that they hunted in packs!” says Emily Lindsey, PhD, assistant curator and excavation site director at the La Brea Tar Pits & Museum in Los Angeles. “That’s terrifying.” Fossils of many saber-toothed cats have been found at the La Brea site—they would have been attracted there by prey animals that were stuck in the asphalt (a thick substance that accumulates when crude oil bubbles up from the ground) and then gotten stuck themselves. Love prehistoric creatures? Check out the coolest dinosaur museums in the world.

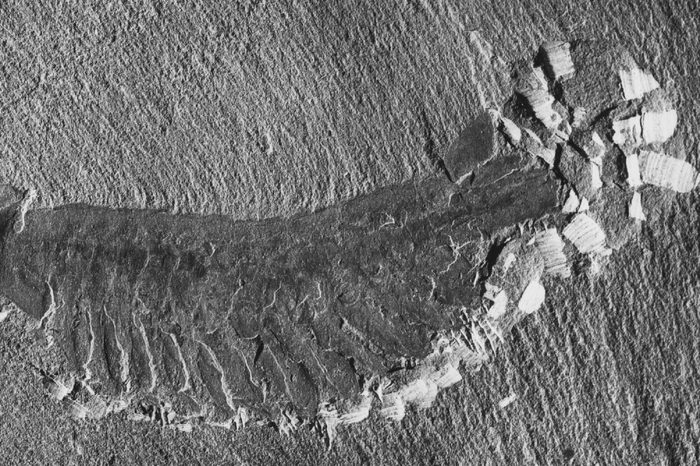

Arthropleura

At more than six feet long, these millipede-like creatures were the biggest arthropod (a group that includes invertebrates like insects, spiders, and crustaceans) to have scuttled around on the Earth—or at least, it’s the biggest one we know about so far. “It’s a phenomenon in the late Paleozoic period that we had these large arthropods,” says Conrad Labandeira, PhD, a senior research scientist in the department of paleobiology and curator of fossil arthropods at the Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History. Scientists aren’t completely sure why bugs got so big during that time (about 300 million years ago), but Labandeira says the main theories are that having a lot of oxygen in the atmosphere (it made up about 30 percent of the air then, compared with around 21 percent now) helped them grow and that there wasn’t anything around to eat them. “On land, the largest vertebrates were probably smaller than some of these arthropods,” he says. One comforting thought: Arthropleura probably wasn’t a predator, since it was related to millipedes, which eat decomposing organic matter. Find out the ancient mysteries that still baffle scientists today.

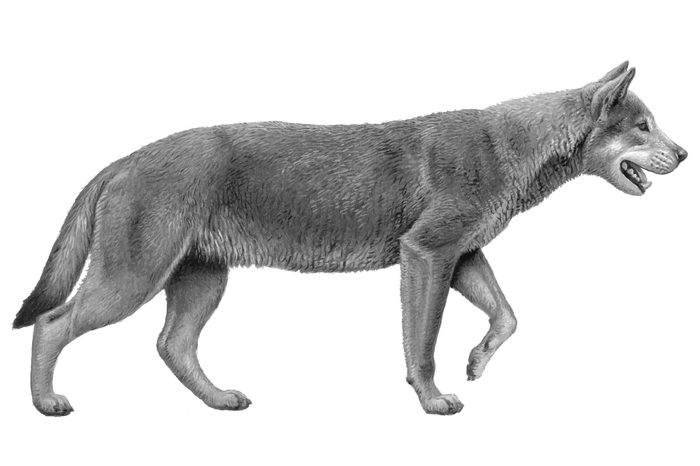

Epicyon

Before dire and gray wolves roamed North America, an even bigger member of the canine family (the biggest member ever, in fact) was here. Epicyon lived between 12 and 6 million years ago, and was the size of a grizzly bear, weighing as much as 300 pounds, according to the Florida Museum. That’s like two Newfoundland dogs or three Great Danes!

Short-faced bears

Those big millipedes probably wouldn’t have fared so well against the largest bear species that ever lived, but the bears appeared a few hundred million years too late. They get their name from the shape of their heads: “Because they were “short-faced,” these giant bears had a much stronger bite force than modern bears, even grizzlies,” says Lindsey. “Also, they had long legs and could run fast!” Some of the North American bears found in the La Brea Tar Pits would have weighed more than 2,000 pounds (modern polar bears only grow up to 1,600 pounds, for comparison), but their South American cousins are likely to have tipped the scales at 3,500 pounds and grown to be 11 feet tall standing up! Find out the 13 myths about dinosaurs it’s time to stop believing.

Megalodon

In the world of big predators, even 11-foot bears wouldn’t want to tangle with the biggest sharks that ever lived. From 16 million years ago to about 2 million years ago, 50-foot-long creatures (that’s triple the size of scary-enough great white sharks today) preyed on whales, apparently biting off their fins to immobilize them. “Modern great whites will scavenge on a whale, but not actually take a [live] whale,” Peter Klimley, a shark expert at the University of California at Davis, told National Geographic in a 2008 interview. According to some studies, a megalodon’s bite was strong enough to crush a car. Amazingly, most of what scientists know about this mega-predator comes from studying its teeth—like modern sharks, the rest of its skeleton was cartilage, which decomposes much more rapidly than bone and leaves few fossils. Don’t miss these fascinating facts about the sharks of today.

Megapiranha

Although it couldn’t have crushed a car in its mouth, the jaws of this extinct relative of modern piranhas could exert a force of up to 50 times the fish’s own weight—pound-for-pound, that makes it a stronger biter than even megalodon. Megapiranhas weighed 20 to 30 pounds (compared with 2 pounds for the modern version) and lived in South America between 10 and 6 million years ago, when the snakes, fish, and crocodiles they likely fed on were also gigantic. But there are plenty of wacky and weird sea creatures living today, too!

Meganeura

What’s so scary about a dragonfly? If you were a smaller bug or one of the amphibians or other vertebrates milling around a pond hundreds of millions of years ago, you definitely wouldn’t want to be spotted by Meganeura, the largest known flying insect, which had a wingspan of about two and a half feet. They lived during the same time as Arthropleura, a period known as the Carboniferous. “This experiment in gigantism probably lasted only maybe 30 million years or so,” Labandeira says. The huge arthropods either went extinct or evolved to become smaller, and again, no one is exactly sure why. The oxygen content in the atmosphere did decrease, but big amphibians were also developing: “One theory is that you had the emergence of much larger vertebrates that were able to consume these things, so size was no longer an adaptive feature,” says Labandeira.

Dire wolf

Another big predator that’s commonly found in the La Brea Tar Pits, this wolf species was about the same length as the modern gray wolf, but it weighed quite a bit more—as much as 175 pounds. “Dire wolves had stronger jaws than today’s gray wolves, which meant (among other things) that they were good at crushing bone,” says Lindsey. Nonetheless, they went extinct about 10,000 years ago, while their smaller cousins are still around—gray wolf populations have made a comeback in recent years thanks to reintroduction programs in places like Yellowstone National Park. Among the dire wolves’ favorite foods was the western horse, which lived in North America until about 11,000 years ago. Horses died out in the Americas and only returned in 1493 when Christopher Columbus’s crew brought them along on ships on their second voyage. This hiker saved the life of a wolf—and four years later, the wolf remembered him.

Obapinia

Some creatures seem pretty creepy even though they’re not enormous—like this 3-inch arthropod: “Opabinia was a flat-bodied swimmer with five eyes and thirty swimming fins and a long tube sticking off the front of its face with what looks like a Venus fly trap on the end,” Lindsey says. It probably stuck that long tube down into the sandy seabed to catch worms. Find out the 11 wild animals you didn’t know were endangered today.

American lions

Along with short-faced bears, these lions were the biggest predators that were preserved in the La Brea Tar Pits. “American lions were about 20 percent bigger than modern lions,” Lindsey says. They went extinct about 13,000 years ago, around the same time as the mammoths and other large animals they would have preyed upon. Researchers imagine that the American lions, short-faced bears, and saber-toothed cats that ended up stuck in the asphalt at La Brea were attracted there by struggling prey animals and that as predators got stuck, more predators took an interest and ventured out into the sticky marsh. It’s hard to imagine all those super-sized beasts flailing away helplessly together, but that’s why about 90 percent of all the mammal fossils that have been found there belong to carnivores.

Josephoartigasia monesi

How do you feel about rodents? Get a little creeped out by mice and rats? If so, the Josephoartigasia monesi might be the reason you’re glad you live now instead of 3 million years ago. At about 2200 pounds (about the size of a modern bull), the South American animal was the biggest rodent we’ve ever found remains of. It had giant front teeth that researchers think it probably used like elephants use their tusks, to root around in the dirt for food and maybe to fight off predators, according to a 2015 article in the Journal of Anatomy.

Titanoboa

If a melee of drowning carnivores doesn’t freak you out, how about a 40-foot snake? Researchers have had a hard time figuring out just how big Titanoboa was when it lived in South America about 58 million years ago, just a few million years after non-avian dinosaurs went extinct, because they haven’t ever found all the vertebrae of a single animal in one place—and it would have had an awful lot of vertebrae! Using what they’ve got, they estimate that the snake would have weighed about a ton, according to a 2012 article in Smithsonian. For comparison, modern anacondas can grow up to 29 feet long and weigh 550 pounds. You won’t believe that these strange animals are actually real and exist today.

Quetzalcoatlus

Terrifying animals didn’t occupy only the ground and the water—imagine a predatory creature the size of a giraffe with a 33-foot wingspan flying through the air. Quetzalcoatlus northropi lived during the Cretaceous period, alongside dinosaurs, and might even have eaten smaller ones. A theory detailed in a Wired magazine article in 2013 suggests that they mostly hunted by walking around like a stork, plucking plants and small animals up off the ground with their 6-foot beaks. But when they took to the air, researchers think they were graceful and powerful fliers—Quetzalcoatlus had hollow bones like modern birds, so where giraffes weigh as much as 2,800 pounds, these creatures only carried about 550 pounds up into the air, where they might have been able to fly and glide for days at a time. Fossils show that they were covered with hair, which probably helped them regulate their body temperature during flight.

Terror birds

Quetzalcoatlus wasn’t a bird, even though it could fly, but there was a bird that was so deadly and frightening that it was named after fear: the terror bird. And these birds didn’t even fly! Terror birds, which got as big as 10 feet tall, developed in South America around 60 million years ago, during a period when there were few other predators on the continent (there were wolves and saber-toothed cats in North America, but there wasn’t a land bridge through Central America yet). Terror birds occupied the top tier of the food chain, using their large hooked beaks to kill prey until they went extinct around 2 million years ago. Read up on the 14 animals that could disappear in your lifetime.