A new understanding of an old process

Prior to 2020, impeachment was one of those things we learn about in high school social studies class, then tend to forget about. But when impeachment is in the news, it’s hard to ignore—especially under the current circumstances. On January 13, 2021, not only did the House of Representatives vote to impeach President Donald Trump for a second time—the first time that has happened in the history of the United States—it also came at the very end of his term. That means that in addition to the usual confusion around impeachment, this particular impeachment comes with even more questions. Reader’s Digest spoke with political scientists, lawyers, and policy experts to set the record straight about what really happens during the impeachment process. To get a better idea of what other rules apply to the person holding the highest office in the land, check out these 10 everyday things no president is allowed to do while in office.

People other than presidents can be impeached

The first point to clear up is that the impeachment process as outlined in the U.S. Constitution applies not only to the president but to the vice-president and other officials, including Supreme Court justices and federal judges, Jaye Pool, PhD, an independent political observer and host of the Potstirrer Podcast tells Reader’s Digest. “Impeachment proceedings have occurred against a handful of judges, and still fewer have been removed from office, most recently in 2010,” she explains. Members of Congress are exempt from the impeachment and removal process, but they’re not off the hook: Article I, Section 5 of the Constitution outlines a different process that allows for the removal of congressional representatives and senators.

Other public officials to have been impeached include one Supreme Court justice (Samuel Chase in 1805), 14 federal judges, a senator (William Blount in 1797) and a cabinet secretary (William Belknap in 1876), Bernard Brennan, PhD, assistant professor of political science at Johnson & Wales University tells Reader’s Digest.

Impeachment does not mean immediate removal from office

There’s a common misconception that when a president is impeached, they are immediately fired and removed from office. As it turns out, what we often refer to as “impeachment” is actually two separate processes with several steps within it, Jaye Pool, PhD, an independent political observer and host of the Potstirrer Podcast tells Reader’s Digest. “Impeachment is the process where the House of Representatives investigates and essentially chooses to indict the president or charge him with offenses that could disqualify him from the presidency,” she explains. “These charges are referred to as articles of impeachment.” Removal, or conviction, on the other hand, is the process where the Senate holds a trial and, by a two-thirds vote, can vote to remove the president from office. If you were wrong about impeachment, here are 25 other words that don’t mean what you think they do.

Impeachable offenses aren’t necessarily illegal

According to Pool, the U.S. constitution states that disqualifying offenses for impeachment are “treason, bribery, or other high crimes and misdemeanors.” While most often, charges that are levied against a president are for illegal activity, this isn’t necessarily the case. Still confused over what’s legal? Here are 18 things you think are illegal, but aren’t.

Being impeached doesn’t bar a president from holding future office

When the Senate votes to convict a president, that doesn’t automatically bar them from running for or holding public office in the future. Peter J. Smith, a professor at The George Washington University who specializes in constitutional law and civil procedure tells Reader’s Digest. “Under the Senate’s approach, there would be a separate vote on whether the [convicted president ] ought to be disqualified [from holding public office in the future],” he explains. And while a two-thirds vote (or 67 of the Senate’s 100 members) is required to convict a president who has been impeached, Smith says that the Senate has always asserted that banning someone from holding public office again in the future requires a bare majority vote of 51.

At the same time, the Senate vote required to ban someone from holding public office isn’t addressed in the Constitution. However, Smith points out that even if a two-thirds vote was required, if two-thirds of the Senate had already voted to convict the president, there’s a good chance they’d also vote to bar them from ever holding public office again. “That would be particularly true if he had already left office, because in that case, the only practical reason to convict would be to disqualify him from running again,” Smith explains.

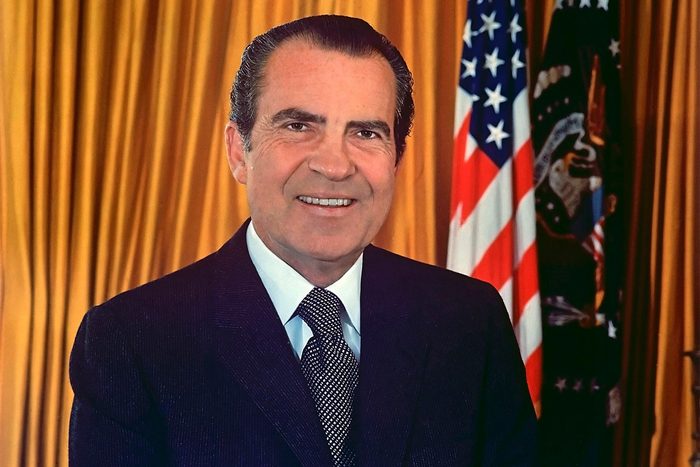

Richard Nixon was not impeached

Whenever the subject of impeachment comes up, Richard Nixon’s name typically follows closely behind. However, Nixon announced his resignation on August 9, 1974, before any articles of impeachment were issued. “He likely would have been impeached and convicted if he had not resigned,” Pool explains. In the mood for more presidential trivia? Here are 52 astonishing facts you never knew about U.S. presidents.

But three U.S. presidents have been impeached

To date, three presidents have been impeached by the House of Representatives: Andrew Johnson in 1868, Bill Clinton in 1998, and Donald Trump in 2019 and 2020. Jim Ronan, PhD an adjunct professor of political science at Villanova University, tells Reader’s Digest. “In Johnson’s case, he was saved by a single vote in the Senate trial, and thus remained in office,” he explains. “There was also a bit of a historical anomaly in that Senate Majority Leader Ben Wade was also next in line for the presidency, and thus was leading the proceedings that could have made him president.” In Clinton’s case, a conviction was never a real possibility: the Senate vote was 50-50—well short of the 67 votes that are required.

In fact, a president can be impeached twice

When the House of Representatives voted to impeach Trump on January 13, 2021, that marked the second time the body had taken that action during his administration—making him the first president in American history to be impeached twice. His first Senate trial took place in February 2020, and a conviction did not take place. It has yet to be seen whether the Senate will vote to convict Trump this time—although it’s also not entirely clear whether an impeachment trial can take place after a president has left office.

An impeachment trial can likely take place after a president has left office

The Constitution doesn’t specify whether the Senate can hold an impeachment trial for presidents after they’ve left office—meaning it could go either way. While there is historical precedent of an impeachment trial happening after a former Secretary of War left office in 1876, Smith notes, this isn’t something that has happened before to a president. “That’s still a live question,” he says. “If Trump leaves office at noon on January 20th having been impeached, there’s no longer a need to remove him from office. But there might still be a strong argument to disqualify him from running for office or holding some other office again.”

If a president is removed from office, it doesn’t mean a change of the party in power

As political as impeachment may be, some may forget that even if a president is removed from office, the party they represent is still in power. For example, if Trump was removed from office following the February 2020 Senate trial, Vice President Mike Pence would have become president, and Republicans would have still controlled the White House, nominate similar sorts of federal judges, and pursue the same general policy agenda, explains Sam Nelson, PhD, associate professor of political science and chair of The University of Toledo Department of Political Science and Public Administration.

Impeachment isn’t a criminal trial

Another major misconception about impeachment is the belief that it is somehow a “legal” process—like a criminal trial, Devin Schindler, JD, a constitutional law professor at Western Michigan University Cooley Law School tells Reader’s Digest. In fact, impeachment is a political process. “The Constitution does not define the term ‘high crimes and misdemeanors,’ which means that the House of Representatives and the Senate ultimately get to define that term,” Schindler explains.

Impeachment isn’t a way to remove a president if they are disliked

Contrary to what it might sound like by the way the word “impeachment” is thrown around, the president can’t be impeached simply for bad behavior or because Congress disagrees with his policy positions, Mike Purdy, presidential historian and author of 101 Presidential Insults: What They Really Thought About Each Other — and What It Means to Us tells Reader’s Digest. “Impeachment and conviction must meet the constitutional standard,” he explains. “That being said, impeachment and conviction are ultimately political processes and there is some ambiguity about what constitutes ‘high crimes and misdemeanors.’ Or as Gerald Ford once put it when he served in Congress, ‘an impeachable offense is whatever a majority of the House of Representatives considers it to be at a given moment in history.'”

If a president is impeached and convicted, they won’t necessarily lose the perks that come with (and after) the job

For clarity on this, we must look to the Former Presidents Act of 1958, which Smith says was enacted to ensure that former presidents would be able to make ends meet following their time in office. In addition to providing them with a pension equivalent to the amount of money they would have been earning in office, the federal regulation also stipulates that former presidents get an appropriation for office staff, an office space furnished by the government, and a travel allowance.

But according to Smith, the most important part comes later, when the term “former president” is defined. “It defines a former president as someone who was president, who is not currently president, and whose service in office terminated other than by removal, pursuant to section four of article II of the Constitution,” he explains.

And here’s where it can get confusing. If, for example, the Senate convicts Trump of the current impeachment charges, Smith says that Trump could make the argument that he wasn’t removed from office as a result of the impeachment process, and instead, left office when his term expired at 12:01 p.m. on January 20th. If that argument is accepted, he would retain all of the perks and privileges that come with being a former president.

But that’s not the only way to approach this scenario, Smith says. “The way I would read the statute—and the way I think a lot of other lawyers and judges would—would be that Congress was not thinking about the possibility of a president who disgraced himself so late in office that he couldn’t be impeached and convicted until after he had left,” he explains. Instead, his interpretation of the Former Presidents Act is that someone convicted of high crimes and misdemeanors would not be entitled to a pension or any of the other perks mentioned in the law.

Interestingly, the Former Presidents Act doesn’t say anything about Secret Service protection for former presidents, so Smith says whether or not a president is convicted following impeachment, they would still be eligible for that privilege. Perks or not, many presidents have gone on to do other things following their time in office. Here are 13 unlikely jobs U.S. presidents held after the White House.

A prison sentence can’t be the result of the Senate convicting a president of an impeachable offense

Prison is not on the table as a consequence of impeachment and conviction, according to Smith. As discussed earlier, the only two actions that can result from a Senate conviction following impeachment are the president being removed from office and disqualified from holding future public office. However, Smith explains that if a president does something while in office that would warrant criminal prosecution, then they can be indicted and convicted of that—though it would be separate from the impeachment process.

This raises several unanswered questions in relation to Trump, Smith says, because “we have never really been forced to grapple with the question: ‘Can someone who was president be prosecuted for something he did while he was president?'” While an impeachment conviction won’t land them in prison, here are things that former presidents aren’t allowed to do after leaving office.

The founding fathers didn’t envision impeachment playing out the way it has

For starters, the founding fathers did not anticipate the rise of political parties, and thought that each of the three branches of government would serve as a check and balance on the other branches, Purdy explains. Instead, in our current political environment, loyalties lie within political parties rather than branches of government. Also, as he points out, “the founding fathers did not envision impeachment and conviction as a way to undo the results of an election, but as a means to protect the integrity of the constitutional framework established in the constitution.” You may be shocked by the U.S. Constitution myths most Americans believe.

But, we are not in a constitutional crisis

The framers of the constitution anticipated that there might be leaders who abuse power, and they provided impeachment as a tool to deal with it, Peter Hanson, PhD associate professor of political science at Grinnell College in Iowa and author of Too Weak to Govern: Majority Party Power and Appropriations in the U.S. Senate tells Reader’s Digest. During both of Trump’s impeachments, the House of Representatives followed the constitutionally prescribed path for addressing allegations that power has been abused and the public trust has been violated, Hanson explains. Instead, he notes that “a real constitutional crisis requires the breakdown of the constitutional system, such as if the president would refuse to leave office despite being convicted by the Senate.” At this point, that is no longer a possibility for Trump, whose term ended on January 20, 2021—prior to a Senate trial or conviction taking place for his second impeachment. Next, read on to learn presidential firsts you didn’t learn about in school.

Sources:

- Jaye Pool, PhD, an independent political observer and host of the Potstirrer Podcast

- Peter J. Smith, a professor at The George Washington University