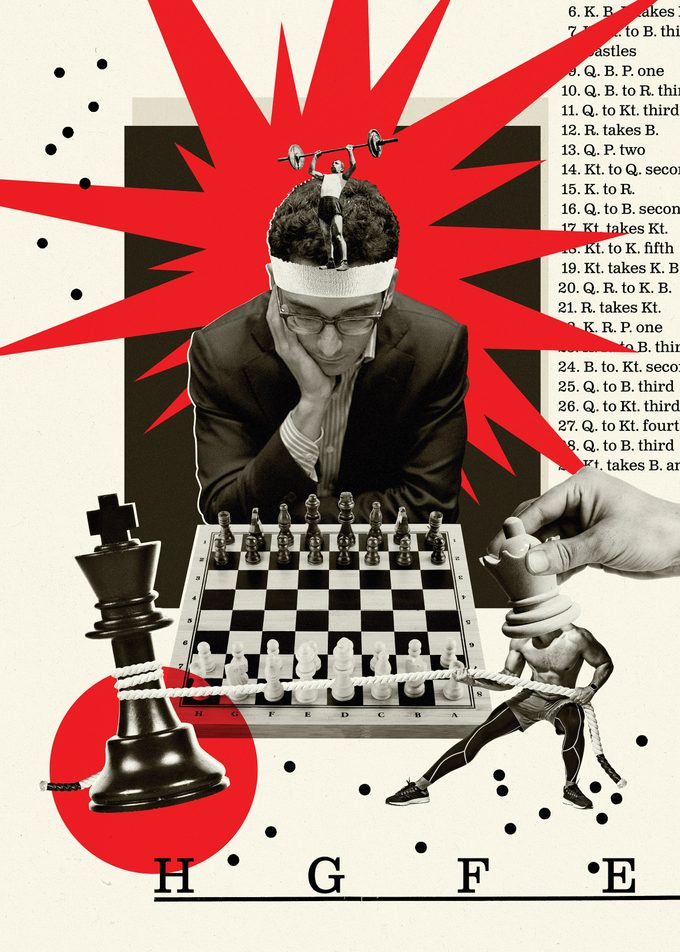

The Secret These Chess Champions Use to Win Isn’t Skill—It’s Physical Workouts

Updated: Nov. 25, 2022

To stay on top of their mental game, the world’s best chess players do serious workouts—physical ones.

On a blustery day in early March, Fabiano Caruana decides to get away. He drives three hours west from his St. Louis apartment to a 2,000-acre compound in rural Missouri owned by a friend.

At 7:30 the next morning, he heads out for an hour-long run with his training partner, Cristian Chirila. As he’s jogging, it’s easy to mistake him for a soccer player. At five foot six, Caruana has a lean frame, his legs angular and toned. He has a packed schedule for the day: a five-mile run, an hour of tennis, half an hour of basketball, and an hour of swimming.

But Caruana is, in fact, an American grandmaster in chess, the number two player in the world. His training partner, Chirila? A Romanian grandmaster. And they’re doing it all to prepare for the physical demands of … chess? Yes, chess.

It seems absurd. How could two humans—seated for hours, exerting themselves in no greater manner than intermittently extending their arms a foot at a time—face physical demands?

Still, the evidence overwhelms.

The 1984 World Chess Championship was called off after five months and 48 games because defending champion Anatoly Karpov had lost 22 pounds. “He looked like death,” grandmaster and commentator Maurice Ashley recalls.

In 2004, winner Rustam Kasimdzhanov lost 17 pounds during the six-game world championships.

In October 2018, Polar, a U.S.-based company that tracks heart rates, monitored chess players during a tournament and found that 21-year-old Russian grandmaster Mikhail Antipov had burned 560 calories in two hours—roughly what Roger Federer burns in an hour of tennis.

Grandmasters in competition are subjected to a constant torrent of stress. That causes their heart and breathing rates to increase, which forces their bodies to produce energy.

Meanwhile, players eat less during tournaments, simply because they don’t have the time or the appetite.

Stress also leads to altered—and disturbed—sleep patterns, which in turn cause more fatigue and can lead to more weight loss. A brain operating on less sleep, even just one hour, Kasimdzhanov notes, requires more energy to stay awake during the chess game.

It all combines to produce an average weight loss of 2 pounds a day, or about 10 to 12 pounds over the course of a ten-day tournament.

To combat the stress, today’s players have begun to incorporate strict food and fitness regimens to increase oxygen supply to the brain during tournaments, prevent sugar-related crashes, and sustain their energy. “Physical fitness and brain performance are tied together,” Ashley says.

According to Ashley, India’s first grandmaster, Viswanathan Anand, does two hours of cardio each night to tire himself out so he doesn’t dream about chess. Kasimdzhanov plays tennis and basketball every day. Chirila does at least an hour of cardio and an hour of weights to build muscle mass before tournaments.

But not one of these grandmasters has perfected his fitness routine the way the current world champion, Magnus Carlsen, has.

In 2017, Carlsen realized he had a problem. The reigning world number one for four years felt his grasp on the title loosening. He was still winning most tournaments, but his matches were lasting longer, the victories less assured. He was waning in the final hour of games. He noticed younger players catching up to him.

So Carlsen visited the Olympic training center in Oslo, Norway, with his father, seeking advice from performance specialists. Their suggestion was deceptively simple: “Cut back on the orange juice you drink during tournaments.”

Carlsen had relied on a mix of half orange juice, half water for an energy boost since he was a child. But now, in his late 20s, his body was no longer breaking down the sugar as quickly, leading to sugar crashes. The nutritionists suggested that he instead drink a mixture of chocolate milk and plain milk, which contains less sugar but would also supplement his body with calcium, potassium, and protein.

“It kept his blood sugar at a reasonable level without too big a variation, and he felt less tired during key moments in tournaments,” his father says.

But that was merely the beginning of Carlsen’s makeover. Since then, he has trained his body for chess. Before the world championship last year, he went skiing every day and tweeted that it strengthened his legs and his willpower. He hired a personal chef who travels with him to ensure he’s eating the right combination of proteins, carbs, and calcium.

During tournaments, Carlsen focuses on relaxing and conserving energy. He chews gum during games to increase brain function without losing energy; he taps his legs rhythmically to keep his brain and body alert.

He has even managed to optimize … sitting. That’s right. Carlsen claims that many chess players crane their heads too far forward, which can lead to a 30 percent loss of lung capacity. And, according to Keith Overland, DC, a chiropractor who has worked with the U.S. Olympic Training Center, tilting your head 60 degrees forward increases stress on the neck by nearly 60 pounds, ultimately resulting in headaches, irregular breathing, and reduced oxygen to the brain.

Instead, Carlsen rests his lower back against the chair so it retains a natural curve, keeps his feet firmly on the ground, and leans forward at about a 75-degree angle. In this position, he’s not too far forward to limit his oxygen and not so far back as to require extra energy.

Carlsen has also reduced his schedule to six to eight tournaments a year (as opposed to the 12 to 14 of most elite players), taking months off to recuperate after each one.

Back in Missouri, Caruana and Chirila hole up in the dining room for six hours of chess. Afterward, Caruana looks exhausted, his glasses askew. Still, he grabs a handful of nuts and heads out for a final hour of tennis before dinner.

After dinner, he passes on the chocolate pudding pie. “No dessert for me today,” he says.

Last year, Caruana gave up alcohol before the world championship. This time, he has chosen sugar. It’s a habit he picked up from Carlsen, who is showing signs, at long last, of being mortal. After a run of eight consecutive tournament victories, the Norwegian dropped ten games at a competition in August.

It’s the opening Caruana has been waiting for. In his mind, Caruana knows what he has to do; he just needs his body to hold up.

“Sometimes you have to shock your body into listening to you,” he says.