The dog days of summer

Dogs are cute and lovable all year round, so what do dogs have to do with hot summer days, specifically? Well, this animal phrase actually refers, not to real dogs, but to astronomical ones. Ancient Greeks believed that the hottest days of the year corresponded with the days Sirius, the Dog Star, rose in the sky before the sun. (The rising of Sirius actually varies based on your position on Earth, but for the Greeks, it was always during midsummer.) Back then, the extreme heat was often associated with misfortune, such as fevers and droughts. Today, though, the “dog days” are just an excuse to make memes of cute dogs lounging around in sunglasses.

Straight from the horse’s mouth

How did horses become the animal synonymous with a reliable or direct source in this idiom? No, it’s not because “horse” rhymes with “source.” It actually has to do with horse racing. Around the turn of the 20th century, the jockeys and trainers were the people closest to racehorses (both figuratively and physically), and therefore were the best sources of pre-race tips. This idiomatic expression developed to suggest that hearing such a tip “straight from the horse’s mouth” would be a tip even better than the best. There’s also a theory claiming that the phrase may have to do with the fact that examining a horse’s teeth could provide information on its physical condition.

Cat got your tongue

Unfortunately, there’s no definitive known answer for how this animal phrase came to be. Cats do not literally steal tongues, so we can only speculate as to where it comes from. And a few (appropriately gruesome) suggestions have gained popularity, from the idea that the ancient Egyptians cut out the tongues of blasphemous folk and fed them to cats to the idea that British Royal Navy prisoners whipped with a “cat-o’-nine-tails” device would remain silent for days after due to the pain. Other sources, however, claim that these tales are completely false, and, indeed, there’s no concrete evidence to support them. What we do know for sure, though, is that this is one of the English language’s most confusing, bizarre idioms most capable of making non-native speakers do a double-take. But English is far from the only language with wacky idioms with hilarious translations.

Doggie bag

Here’s another one for the dog lovers. Though the practice of taking home uneaten food dates back to the ancient Romans, “doggie bags” as we know them today didn’t come to be until the 1940s. During World War II, the prevalence of food shortages led to people feeding leftover food to their pets to reduce food waste. (Microwaves weren’t around yet to reheat food!) Restaurants, which weren’t yet in the habit of offering people the option of taking food home, began to offer the earliest “doggie bag” options. They began as “Pet Pakits” in San Francisco cafés and “Bones for Bowser” bags in Seattle hotels, and grew from there. Time went on, and the war shortages ended, reheating food became a much easier and more convenient possibility, and restaurant portions got bigger—all of which ushered in the practice of people bringing home leftover food for themselves rather than their pets.

Scapegoat

Less an idiom than an actual word, “scapegoat” did, in fact, used to refer to a real goat. The Bible documents a practice in which Israeli priests would release a goat into the wild on Yom Kippur to represent the cleansing of sin from the nation. Merriam-Webster claims that the English word “scapegoat,” which combines “goat” with “scape” (an old-fashioned way of saying “escape”), first came to be in the 1500s. The word then evolved to mean anyone blamed and then exiled or punished for the perceived well-being of the rest of a group. Plenty of other phrases we use all the time can also trace their origins back to the Bible.

Wild goose chase

Contrary to what you might think, this idiom does not actually come from the idea of chasing a goose around. Back in the day of William Shakespeare, widely considered the first person to actually use this phrase in writing, there existed a popular, quite unusual form of horse racing. In these types of races, a lead racer would follow a winding path. Then a second rider would have to start after the lead racer and follow the first rider’s route exactly. More riders would start the race after that until the “chase” smacked a little of a flock of geese all following the exact course set by the lead goose.

Happy as a clam

Of all the animals to idiomatically refer to as “happy,” why a faceless, shell-concealed, blobby clam? If this phrase strikes you as strange for this reason, you’re not alone. And you’re totally right to be confused, because “happy as a clam” is only half of the expression, making it one of the everyday idioms you’re getting wrong. The original expression, which dates back to the early 19th century, was “happy as a clam at high tide” or “at high water.” And when you learn that clams can only be dug up or harvested at low tide, when water isn’t covering them, you understand why they could be considered very happy at high tide.

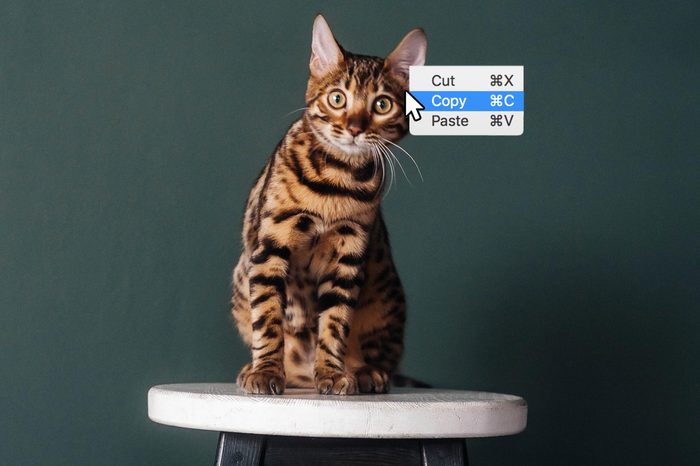

Copycat

We have “monkey see, monkey do,” but also…copy cat? As Slate points out, monkeys and parrots are famous for imitative behavior (and, indeed, both of their names can also be verbs meaning to repeat or mimic). Cats, though? Not so much. The most popular theory is that this phrase wasn’t actually referring to a furry, meowing creature but to an irritating, mischievous person. As early as the Middle Ages, perhaps due to felines’ association with bad omens and demonic behavior (of course the history of superstitions like this one is a whole other story), “cat” was an insult, conveying meaning similar to “scoundrel” or “low-life.” “Judging from this etymological history, a ‘copycat’ isn’t someone who copies, like a cat, but a jerk prone to imitation,” Slate sums up. Actual cats don’t copy or take tongues, and yet, thanks to the strange beast that is the English language, here we are.

Let the cat out of the bag

The negative idiomatic associations with cats continue! But unlike “copycat,” this expression does refer to literal cats—and literal bags! In medieval marketplaces, farmers would purchase a pig and take it home in a bag. A shady vendor, however, might stick a cat in the bag without the customer knowing, duping them into thinking it was—and paying the high price for—a pig. It wasn’t until the customer “let the cat out of the bag” that they’d realize they’d been conned.

Barking up the wrong tree

This idiom is especially funny when you consider that “bark” has two meanings, and one of them is directly related to trees. But this phrase is referring to the barking of dogs, not the bark of trees. The dogs in question are 19th-century hunting dogs, who would chase prey such as raccoons until the prey animal ran up a tree. Then the dogs would stand at the base of the tree and bark, alerting the human hunter in charge of the dogs to where the animal was hiding. But, sometimes, the animal would hop from tree to tree, leaving the dog, quite literally, barking up the wrong tree. Read on to learn the meanings behind more perplexing idioms we use all the time.