Why Desegregation Didn’t Put an End to Racism in America

Updated: Apr. 28, 2021

On the Civil Rights Trail: “What we needed was equality, but what we got was integration.”

Walking down the concrete slope of the “national lynching memorial,” a series of rusted iron columns rise up from the ground around me. Each is marked with a name, a place, and a date. As I proceed, hundreds of them rise higher until they’re suspended from the ceiling—like the haunting “strange fruit” Billie Holiday sang of in the late 1930s (“Black bodies swinging in the southern breeze, Strange fruit hanging from the poplar trees”). On the grass around this morbid passageway, I see more rusted columns, lined up like coffins awaiting burial. This disturbing artwork commemorates the roughly 6,400 victims of lynchings, blacks killed in the United States by white mobs between 1865 and 1870. The visitors around me, white and black, are uncomfortably silent.

Officially known as the National Memorial for Peace and Justice, it was founded by the Equal Justice Initiative in Montgomery, Alabama, and opened in 2018. It is one of the main sites on the Civil Rights Trail, a national network of historic civil rights markers, monuments, and museums located mostly in the southern states. It’s June 2019, and I’ve traveled from Holland to visit a few—and to learn. This is the first day of my road trip through Alabama, Tennessee, and Mississippi, where I’ll also be meeting with veterans of the 1960s protests and campaigns.

Before my trip, I had been surprised to hear about this network of sites. After all, the South is best known to most outsiders for conservative social policies and accusations of suppressing minorities’ voting rights. I had traveled through the region before and enjoyed the hospitality, but when I met locals I had shied away from subjects like religion and politics. And now the region was promoting its new Civil Rights Trail to visitors. I thought it was a good reason to return, albeit armed with healthy skepticism. But that skepticism was the first thing I lost.

It’s no coincidence that a national lynching memorial would be placed in Montgomery: the Alabama capital has played a central role in the darkest history of the United States. In the 19th century, it was a major hub for the American trade in humans. It was also the first capital of the Confederate states when they broke away from the Union in 1861, starting the American civil war. And in the 1950s and ’60s it was a center of resistance against systematic racial segregation.

Around Montgomery’s center, traces of the past are everywhere. I pass the residence of the first Confederate president, Jefferson Davis; the Baptist church on Dexter Avenue where Martin Luther King, Jr., preached; and the place where Rosa Parks was arrested in 1955 because she refused to get up for a white passenger.

Also in the city’s center is The Legacy Museum, founded by the Equal Justice Initiative, the not-for-profit organization behind the lynching memorial; it fights mass incarceration, which overwhelmingly affects people of color and which the organization directly links to the legacy of slavery. The Legacy Museum is in a former “warehouse” for slaves. Its display opens with life-sized black-and-white holograms of enslaved people; they start to talk when you pass the 19th-century holding cells the holograms are projected into. Their stories are based on true ones recorded in the early 20th century by former slaves. In one corner a woman’s hologram quietly sings a spiritual song, and from another cell come children’s voices crying, “Mama, mama….” It is chilling.

The museum’s next section covers the transatlantic slave trade, executed by men from England, Spain, France, Portugal and, yes, my native Holland, between the 17th and 19th centuries. It is a dark period that we Europeans so often regard as American history rather than our own.

Near the exit are large photos from the civil rights movement of the 1960s. A photo of white teenagers angrily shouting at a black student entering their school suddenly makes me realize that the discomfort I’ve felt since I visited the lynching memorial is turning to shame. This is not a scene from distant history. This is my generation, which makes me, a white person, representative of the guilty party. This is the first time I’ve ever been acutely aware of my race.

If these places are impacting me, I wonder how they must affect African Americans. So I ask an elderly lady standing near me. “It makes me want to cry,” she says with a sad smile as her eyes tear up. She tells me that she grew up here in the 1960s and remembers the abuse. She’s lived in the U.S. north for the past 40 years and is back for the first time, on vacation. She’s happy to see that institutions like this exist now and that the South is moving forward. Then, before she walks away, she says: “Thank you for asking.” Those words are strangely comforting, and I forget to ask her name.

The next morning, I meet Dianne Harris in Selma, Alabama, 80 kilometers west of Montgomery. Harris was 15 in March 1965 when hundreds of black citizens crossed the local Edmund Pettus Bridge intending to march to Montgomery to demand the right to vote. They were blocked at the other side of that bridge by the sheriff, his deputies, and a posse of white farmers and off-duty state troopers on horseback. In a violent crackdown on the marchers, 17 were hospitalized. Photos of “Bloody Sunday” appeared in newspapers and magazines around the world.

Harris, who sought shelter in a church with her brother, now works as a tour guide in Selma, and she includes a stop at the Selma Interpretive Center located near the bridge. She tells me it worries her that the younger generation of African American kids know so little about what their grandparents went through. It was partly the fault of the school boards that once kept it out of the curriculum, she says, though Alabama’s civil rights education has notably improved since Harris’s days as a teacher. “But it’s also our own fault. We didn’t teach them, either. We wanted to forget about those days.” It’s the reason, she says, why she is telling the story now, to kids on her educational outreach projects, to her tour guide audiences, and to all who wish to hear.

I leave Selma and drive northwest around five hours to Memphis, Tennessee. This is where Martin Luther King, Jr., was killed in 1968, shot from across the street when he was standing on the balcony of the Lorraine Motel, now a civil rights museum. When I visit, I see an African American family taking pictures, cheerfully posing, thumbs up, under the balcony where King died. It reminds me of a similar kind of disconnect outside Anne Frank House in my hometown, Amsterdam.

My trip takes me south now, toward Jackson. Rather than the direct three-hour route I take a wider, westerly swing through the Mississippi Delta, the flat region between the Mississippi and the Yazoo rivers. The birthplace of the blues—the music of the slaves who toiled here for hundreds of years—the Delta is warm and humid. The young cotton plants stand 20 centimeters high in the endless, treeless fields now worked with massive machines. I pass the Mississippi State Penitentiary, known as Parchman Farm, the notorious prison farm covering some 120 square kilometers along Highway 49. I see prison barracks to the right. Road signs warn that slowing down or stopping is not allowed here for any reason. Back in the early 1960s more than 300 activists called Freedom Riders were held here. I’ll be meeting one of them, Hezekiah Watkins, at the end of my trip.

“You cannot blame today’s kids for not being interested,” says Flonzie Brown Wright when I meet her in the small memorial center she has set up in a former shop in Canton, a sleepy town of 12,000 some 40 kilometers from Jackson. This 78-year-old activist was the first African American election commissioner in Mississippi, in 1968. Now, the African American population of Mississippi has a higher local representation than anywhere in the country, she says. But they have no power. “Gerrymandering,” the targeted redrawing of election districts, ensures that the state is still controlled by conservative white men, she says. “Schools for black children are still inferior,” she says. “The curriculum is decided by the state.” In a history book that most Mississippi school districts use, only five of 100 pages are devoted to civil rights struggles, according to a report published in 2017.

What is needed, says Brown Wright, is a new generation of strong black leaders. And while she supports groups like Black Lives Matter, the now global campaign that was originally started to protest state-sanctioned violence against black people, ideally, she says, this new generation of leaders would include people like Martin Luther King, Jr., and the kind of people who worked with and supported him. And not the version of King, she says, that’s celebrated today—a pacifist dreamer—but the brilliant activist and strategist he actually was. Still, she is optimistic: “I have to be. The slaves never lost hope. They survived on hope.”

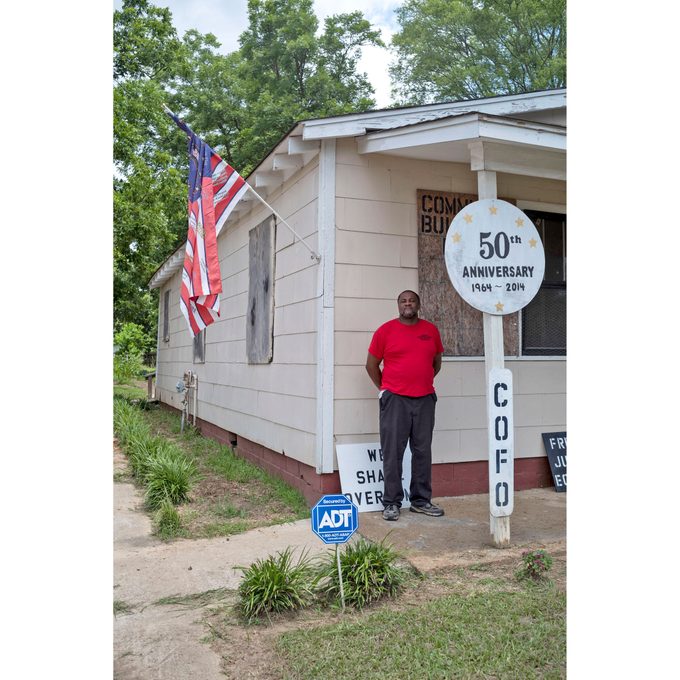

Flonzie Brown Wright takes me to meet Glen Cotton, grandson of the owner of a so-called “shotgun house” that served as a safe house for the Freedom Riders in the early ’60s. The Freedom Riders were local black activists and white volunteers from the north who tried to force desegregation of the Greyhound bus system by refusing to abide by rules that separated seating by race. Cotton has turned the house into a small private museum dedicated to the Freedom Riders and the history of the local black community. He shows me photos of famous activists who came here, including King and Medgar Evers, the field secretary of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) who was shot outside his Jackson home in 1963. Then Cotton shows me a portrait of a group of well-dressed businessmen. “That was the black business association,” he explains. “There’s no such thing anymore.”

“We were better off before desegregation,” he continues. Seeing the surprise on my face, he describes the lively black business community that existed here until the 1960s, when the black middle class owned shops, cinemas, restaurants, and funeral parlors, and when black doctors and lawyers served the community. When desegregation came and African Americans gained the right to be served in the better-equipped white establishments, the black business class suffered and many shops went bankrupt.

“But at least,” adds Cotton, “race relations here in the South are better than they are in the north.” Now I am really surprised, but he insists, and another African American visitor who has walked in on our conversation agrees. I’ll hear more about this on my next and final stop: Jackson.

At the state capital’s splendid new civil rights museum, I meet 71-year old Hezekiah “Heck” Watkins. In 1961 at age 13 he went with a friend to the Greyhound bus station in Jackson to see the Freedom Riders arrive, not knowing they’d been arrested before the bus got there. His friend suddenly pushed him through the door into the station, where police mistook him for a demonstrator. He was locked up on death row at Parchman Farm. After five days, he was finally released.

We talk some two hours about his youth in the segregated 1950s and ’60s. Watkins grew up on a street that separated a white and a black neighborhood. “Little kids from both sides of the street played together, but when we turned six, we went to different schools. And when we turned 12 we had to call them “Mister” and they called us “Boy.”

In 1955, 14-year-old Emmett Till had been tortured and lynched in Mississippi for allegedly whistling at a white woman, but young Watkins was shielded from such horrors by his mother. All he knew was that he had to lower his eyes when a white person approached, and he couldn’t play on the sidewalk. “My mother warned me never to look at a white woman’s butt or eyes,” he says with a smile. “But I had no idea why.”

After Heck’s accidental arrest his naivete was later replaced with a clear view of the harsh racial injustice of the South. It turned him into an activist. Eventually, his mother let him join the Freedom Riders. It led to another 108 arrests, making him the most-arrested activist in the history of the civil rights movement. “Other people counted that, not me,” he says.

In 1965 the struggle seemed to be ending in victory. First the Voting Rights Act was passed by the Johnson administration, guaranteeing African Americans in the South the right to vote, and then the Civil Rights Act officially ended segregation. It did not, however, end racism or undo the wealth gap, says Watkins: “What we needed was equality, but what we got was integration.”

Still, Watkins also confirms what Glen Cotton told me: race relations are better in the South than in the north. Trying to make sense of this, I call Charles “Chuck” Ross, professor of history and African American studies at the University of Mississippi. Ross grew up in Ohio and now works in the South, so he should know from experience. “In the South,” he says, “racism is overt. If you see a guy in a pickup truck with a rebel flag on it, you know he’ll have an issue with black people. In the north it is more covert; you may develop a relationship with someone—then be confronted with racism when you don’t expect it. You don’t have the luxury to relax.”

The South has been forced to deal with its dark past. “There has been a more profound change here than in some areas in the north,” he says. This echoes what others have shared with me on this journey: That the South is moving forward by dealing with the past—through activism, memorials, and museums—while the north pretends nothing was ever wrong.

On a long, sleepless flight home, I ponder the parallels with the country I’m returning to, where open displays of racism in soccer stadiums are loudly condemned, but where any discussion of our colonial past, including the slave trade, is muted because it undermines our idealized image of the Dutch “golden age” of the 17th century. It’s also a place where covert racism translates into situations like lesser job and housing opportunities for people of color. It’s something I’ve always known on an intellectual level, but somehow, that moment of acute awareness of my own race that I experienced in the Montgomery museum has given me a new level of understanding.

This journey is not like other trips I’ve been on. This one will not be over when I land.

For more on this important issue, see our guide to the Fight Against Racism. And, read these 30 powerful quotes that speak volumes in the fight against racism.