“We Have Your Biopsy Results”: What One Doctor Learned from Suddenly Becoming a Cancer Patient

Updated: Jan. 03, 2017

Part of his job is breaking the news about an incurable diagnosis. He never thought he would be on the other end of that conversation.

When I went to see the dermatologist, I had no suspicious spots I wanted examined. It was just a preventive measure you take once you are middle-aged. I’d made the appointment for early in the morning because I’m a doctor—a pediatric lung specialist who treats cystic fibrosis—and I know how the patients pile up as the day goes on. I sat in the waiting room alone on a plastic chair, reading the posters about droopy necks and sagging eyelids, privacy laws and co-payments. At every new doctor’s office, I debate whether to tell the staff that I am an MD; sometimes, when it’s just a checkup, as this was, I’ll remain incognito and see how they treat the civilians. But I always come clean with the doctor in the examining room.

The dermatologist was a thin woman with thin hair and a pair of squarish glasses riding the ridge of her thin nose. I got the impression she was not much of a joker. She began looking me over right away, starting with my face and my bald spot. At first, she talked while she worked, but by the time she got to my arms and hands, her patter had run out and she proceeded in silence: over my elbows, under my arms, down to my thighs and knees and shins, along the tops of both feet, and between my toes. Then to my lower back.

“Huh. How long has this been here?”

I told her I didn’t know what she meant.

“It’s just a precaution,” she said, “but I think we’d better biopsy that.”

The following Tuesday, the phone rings. “I have your biopsy results,” the dermatologist says. Since she is calling to give me the results instead of asking me to come to her office, I assume that the biopsy has come back fine. I never give bad news over the phone. I always deliver it in person so I can see the parents’ reaction and adapt. I am experienced at telling mothers that their babies have a disease with no cure, then quickly adding that what they’ve read or heard from their aunt Martha about cystic fibrosis is out-of-date and that kids who have it do pretty well these days. It’s important to say this face-to-face. I can’t know if my mixture of kindness and reassuring authority is working if we aren’t in the same room.

The biopsy shows malignant melanoma, stage II, the dermatologist says. Her words bypass my brain, flowing directly from my left ear to my right hand, which writes them in block letters at the top of a yellow legal pad, then underlines malignant melanoma. While she talks about the depth of the lesion and the presence of “mitotic figures” in the cell, I think, I am going to die of cancer. Will I go out bravely, seizing the day and having the time of my life? That doesn’t sound like me.

The dermatologist is still talking. I should ask questions, but I’m afraid to seem dumb. She assumes that because I am a doctor, I know what she is talking about. Finally I interrupt her to say I am a lung specialist; I don’t know anything about malignant melanoma. Could she explain it, please?

By now, my yellow page is filled with blue ink, and there are dashes and underlines I don’t remember making. She asks where I want to have the “wide resection” done, and I tell her. She recommends I call them today: “There’s no use in waiting.”

A Google search brings me to a melanoma life-expectancy calculator. I plug in my numbers and the biopsy-result details from the yellow legal pad. The calculator tells me that I will likely die at the age of 73. If the surgeon gets all the cancer, I could live longer. If it has metastasized, I could be dead before I’m 60. But, on average, I’ll have 20 more years. When did I think I would die? How old was Dad when he died?

I arrive at the surgery building downtown at 5:45 a.m., and the waiting room is already full. Groups of three, four, and five people are sitting together. I’m here alone. On the nearest TV, a muscular, out-of-breath man in workout clothes promises us we can transform our bodies in 90 days. At 6:03, a woman comes out of a side door and asks, “Who’s first?”

A woman is called to the desk. The receptionist, whose name is Erta, asks the patient if the man with her is her husband, and the woman laughs and says, “No, he’s my friend.” Erta says, “Honey, he is more than a friend today. Today he is your ‘significant other.’” Erta marries them right there at the desk using a white plastic wristband in place of a wedding ring.

Erta calls my name. She asks for my birthday, and I stumble and give her the wrong year, then correct myself and say it again, twice. Erta attaches the white plastic band around my right wrist. I am just about to tell her that I am a doctor when she says I can sit down now.

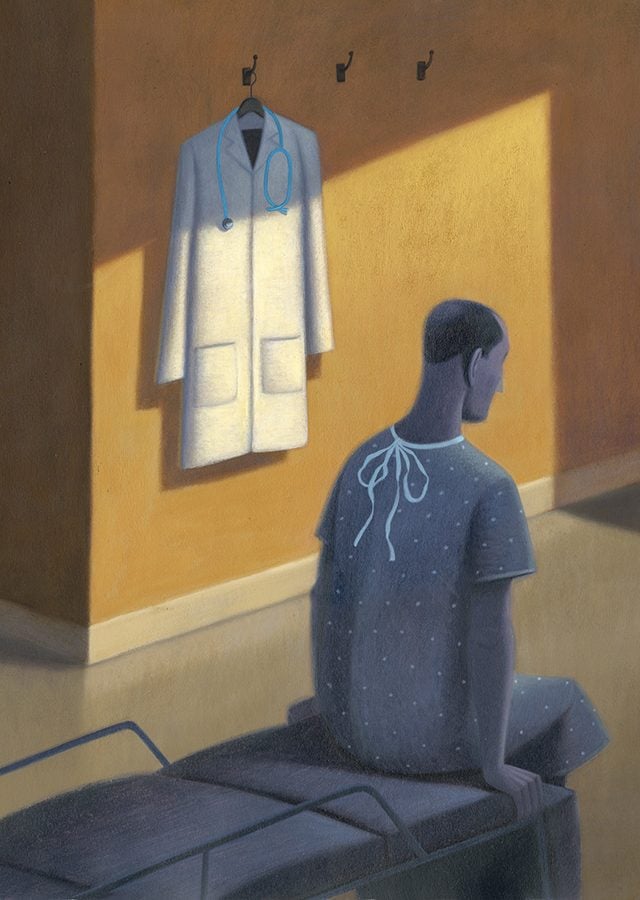

Twenty-five minutes later, a woman in sky-blue scrubs leads me through a pale green hallway to bay E3, where she pulls the curtain behind us. I obediently change into the hospital gown, a marvel of snaps and folds and ties. I wrap it around me but don’t bother fastening it. My usual modesty is gone. This morning, I am not a doctor; I’m just a man in a gown. For a moment, the anonymity frees me to be nervous or uncertain or silly; I can crack jokes or cry, because today I do not have to be in control of my face or my emotions or my fears. The professional manner I have practiced for so long—the low voice, the serious eyes—is unnecessary. I can just be the overweight bearded man in bay E3, the 9:30 a.m. case, here for resection of malignancy with local anesthesia. A patient.

My surgeon parts the curtain and grips my hand in his bony fingers. I can tell he is in a hurry. (I hope it’s not so obvious to my patients when the same is true of me.) When he calls me Mr. Robinson, I do not correct him.

It is time for him to mark the spot that he will cut out. I turn around in the chair, and the starched edge of his white coat brushes my naked shoulder as he moves behind me. I can smell the Magic Marker and feel the cold circle he draws on my back. He asks if anybody is here with me, and I say no. I know what he’s thinking: that he won’t have to go out and talk to the relatives in the waiting room after the surgery is over.

I sense that he wants to get away before I can ask any questions. We don’t need to talk about cell types and incision depth and prognosis and margins—we did that in his office last week—but I want something more from him than nonchalance.

“See you in a bit,” he says, and he leaves.

A nurse named Brian walks in and, with great speed, snaps up my hospital gown and ties the cords in back. Then he puts me in a stretcher chair and pushes me out of the cubicle and down the green hallway to operating room 7. I was not expecting a full OR. Nor was I expecting a nurse to be scrubbed in for a procedure that requires only local anesthetic. The room is set up as though this were a serious operation. There are all the scalpel blades, organized by number and name; the sutures stacked neatly in their boxes; the syringes, each in its individual wrapper. There is the anesthesia machine. The Bovie cautery machine, with its dial for turning up the electric current to cauterize the incision. I try to figure out who is in charge, but no one looks at me or talks to me. What is happening? Why do they need the code cart? Am I really that sick?

I am grateful to lie facedown on the table, because maybe I can close my eyes and imagine that I am somewhere else. Brian puts a sheet over me and straps me down. I go over in my mind what will happen: The surgeon will remove from my lower back an area of skin, blood vessels, nerves, and fat about the size of a deck of cards.

Someone attaches leads to my back and puts an oximeter on my finger to monitor my pulse and the oxygen saturation of my blood. Within a few minutes, the oximeter’s beeping slows, but no one says a word. I imagine they are as practiced as I usually am at ignoring it, but now that the beeping monitor is on me, I think someone should react. Should I say something? If I don’t, I worry that my heart will stop, and my blood pressure will rise, and I will stroke out and never leave this room alive. Did I forget to take my blood pressure medicines this morning? Or was I not supposed to take them? Shouldn’t I know?

I hear the rustle of a gown, and I know that the surgeon is here, though he says nothing. I feel the table being raised and his belly pressing against my side as he leans in close. He asks for lidocaine with epinephrine—the anesthetic—and then announces, “This will sting and burn,” as if speaking to no one in particular. He is right; it stings and burns.

The surgeon checks my sensation with the prick of a needle, and I flinch, so he injects me again. I feel the sting, and then I don’t feel anything, not even any pressure. In my mind, I envision the scalpel cutting a smooth line, brilliant drops of ruby blood rising up, then the incision being deepened by the electric blade of the cautery, white fat shrinking back from the heat and forming a faint gray edge, the blood turning from red to black. I wonder if I will smell my own blood and skin being burned away. And then I do smell it. I lie still and hold my breath.

A sudden pain makes me say “Oh!” in a choked voice. Embarrassed, I clench my teeth. “Sorry,” the surgeon says. “We’re deep.” Then: “That was the muscle.” And: “Another lido with epi, please.” I wince, and the drapes rustle again. I blame myself for flinching and worry he will think I am a weak, silly pediatrician who cannot control himself. The surgeon asks for more Vicryl, an absorbable type of suture. Then a new voice says, “I’m putting Steri-Strips on.”

Brian tells me to stand up. He snaps my gown back up and wheels me out of the room, past people walking the corridors. I do not look anyone in the eye, because I am afraid that my face will show how I feel: shaken and scared and nauseated and numb and angry and sad and relieved all at once. I want to cry and cower under a soft quilt and sleep and dream and wake up in my own bed and not on this stretcher chair in these fluorescent-lit halls that smell of air freshener.

After I’ve dressed, I sign all the forms. Then a nurse points me to the exit and wishes me luck. I am on the far side of the elevators from Erta’s desk. She is still there, reading the paper. The waiting room is brighter now. The television blares ads and weather reports. I walk down the flight of stairs to the lobby, but I don’t want to get in the car and drive home until I am calm. So I take a seat on a bench.

The cancer that was removed from my back will travel quite a bit in the next month. It’s already passed from the hands of the surgeon into the clear plastic jar held by the nurse and then on to the specimen basket at the main OR desk. Later it will move to pathology, where pieces of it will be thinly sliced and pressed between two rectangles of glass. After the pathologist has determined that the margins have no visible cancer, he will place the slides in a cardboard tray for storage. The part of me not thinly sliced and preserved under glass will be unceremoniously incinerated, along with all the other hazardous hospital waste, and the slides will be sent to a file room in Philadelphia. My task now as a patient: to trust that more cancer is not hiding somewhere we did not look—in my lymph nodes, in my bloodstream, in my chest.

I sit for a few minutes more, watching people move through the lobby. This one is a resident. That one is a fellow. There is a nurse-practitioner, an X-ray tech, three medical students, a woman in a wheelchair being pushed by a nursing assistant, a cafeteria worker, a surgeon.

A little girl with a white bandage across one eye (ocular-muscle repair?) waits with her mother by the elevator to the parking garage. I go and stand next to them, then look down at the girl and smile the smile I know works with sick children, and her lips turn up a bit at the edges. When the elevator comes, I hold the door for her and say, “After you, sweetie. You’ve got to move quickly with these hospital elevators. And make sure you hold Mom’s hand.”

I am a doctor again.