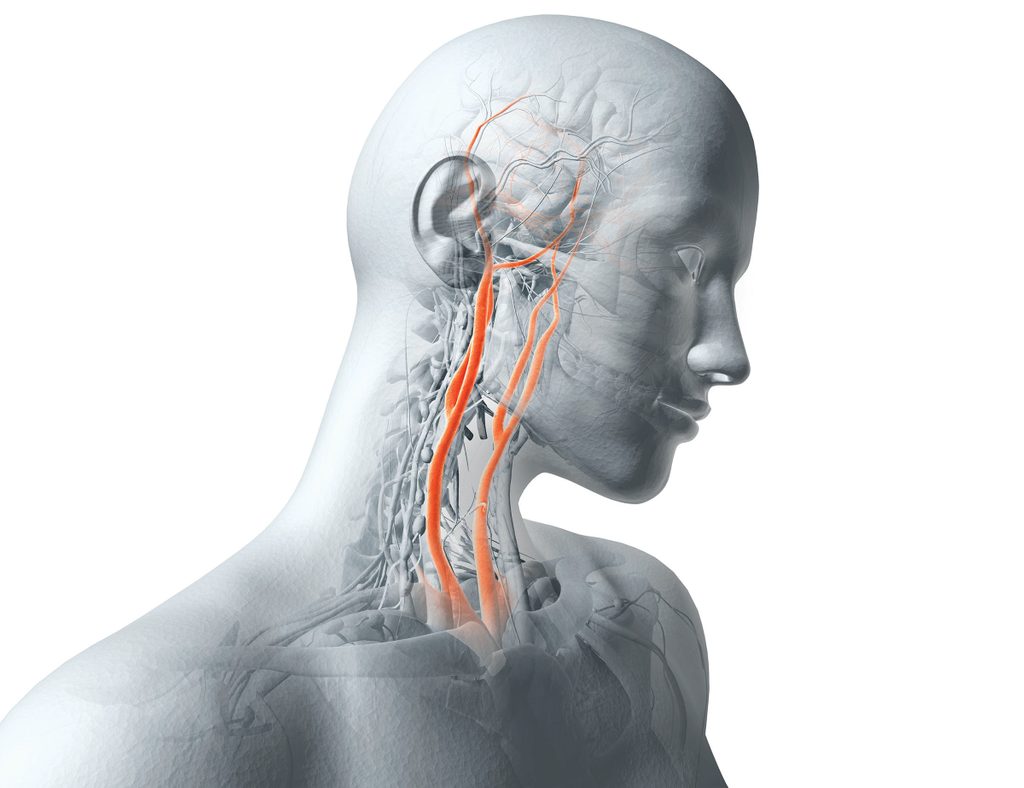

Carotid Artery Surgery: Could It Give You a Stroke?

Updated: Apr. 15, 2016

Know the facts before going under the knife to clear your carotid artery.

[dropcap]D[/dropcap]uring a routine exam after Martha Bowes turned 60, her doctor found that her carotid arteries, large vessels in the neck that supply blood to the brain, were obstructed with plaque. Because she felt fine, Bowes didn’t obsess over her carotid artery blockage—until she found herself in the office of a surgeon. The doctor had completed a procedure on her husband, and the couple were returning for a follow-up.

As the visit wrapped up, the doctor asked Bowes about her carotid arteries (worried, her husband had mentioned the obstruction).

No doubt, Bowes needed an operation, the surgeon said. From his description, Martha got the impression that the procedure, called a carotid endarterectomy, would be as quick and simple as a tonsillectomy. “We go in, make an incision on your neck, and we just clean that [plaque] out,” she remembers him saying. She hesitated; he insisted. “We have to do this immediately, or you’re going to have a stroke,” he said. She booked the soonest appointment she could.

As Bowes awoke from her carotid artery surgery later that week, her mouth wouldn’t properly form words. She looked at the clock on the wall and struggled to tell what time it was. She discovered she couldn’t move her left side. “When I realized that, I was scared,” she says.

Before surgery, Bowes had walked three miles a day around her Lubbock, Texas, neighborhood and traveled throughout Europe and East Africa. Now she lay paralyzed, damaged by a stroke—the very condition she’d had the operation to prevent.

The Rise of a Risky Procedure

[dropcap]B[/dropcap]owes says today that had she known her options, she would have reconsidered going under the knife. An estimated 4 to 5 percent of middle-aged adults have some carotid artery blockage, called stenosis. Every year, about 100,000 to 140,000 people undergo surgery, just as Bowes did, to clear their carotid arteries. Others have a small mesh tube called a stent threaded into one of the arteries to prop it open, a procedure called carotid stenosis. Yet despite what the surgeon told Bowes, other experts believe her stroke risk was probably so small that she would have been fine had she taken drugs to lower cholesterol and followed a healthy diet.

Stroke is one of the most common causes of death and disability in the United States, affecting almost 800,000 people a year. But only about 20 percent of strokes arise from a blockage in a large artery like the carotid. The vast majority of people with a blocked carotid artery will die with it, not because of it. One JAMA Neurology study followed 3,681 heart patients from 1990 to 2014; of the 316 people who developed carotid disease, only one had a stroke during that period.

Clearing a clogged carotid artery could be a solution in search of a problem. During or after a procedure, bits of plaque may break free and lodge in the small vessels of the brain, triggering the stroke you’re trying to stop. The likelihood depends on many variables, including the surgeon’s skill. One 2015 study in the Journal of the American College of Cardiology compared surgery outcomes of carotid artery stenting across 188 hospitals. Stroke risk after carotid stenting was anywhere from zero percent to nearly 19 percent.

[pullquote] Clearing a clogged carotid artery could be a solution in search of a problem. [/pullquote]

In the view of some experts, drugs that lower cholesterol, along with weight and blood pressure control, are so powerful that if patients have no symptoms (such as a ministroke), they’re better off leaving the carotid artery in peace. If a patient has symptoms, however, most doctors advise intervention. (By some calculations, close to 90 percent of U.S. patients who undergo procedures on their carotid arteries never had symptoms.)

“This is the most contentious debate in cardiovascular disease,” says Christopher White, MD, director of the Ochsner Heart and Vascular Institute in New Orleans, Louisiana. One professional medical meeting had a session titled “Ill-Advised, Malpractice, or Criminal?” to describe the popularity of carotid artery stents.

Does Carotid Artery Surgery Help or Hurt?

[dropcap]M[/dropcap]artha Bowes wishes she’d known that plaque in the carotid artery was unlikely to be a medical emergency. In fact, in 2014, the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force advised against routine carotid screening. Nonetheless, such tests are still done often. One study noted a 27 percent increase among Medicare beneficiaries from 2001 to 2006. This past November, a JAMA Internal Medicine report named carotid screening as one of the most overused procedures in 2014.

Doctors check for blockages without reason. Health fairs offer free tests. One company sends mailers that urge people to find plaque buildup “so you and your doctor can do something about it before it’s too late.”

While removing plaque seems to make intuitive sense, some studies don’t always support that thinking.

Two major ones that compared surgery like Bowes’s with medical treatment were published in 1995 and 2010. Stroke risk was about 30 percent lower after surgery, which would be a decisive victory for Team Surgery except for this: Powerful cholesterol-lowering statin drugs came into widespread use only after the research was under way, says David Spence, MD, a neurologist at the University of Western Ontario. Patients in the landmark studies mostly took blood thinners. This instantly outdated the results. There is also debate over which procedure—stents or surgery—is best; still more studies have yielded conflicting interpretations. A head-to-head comparison of the two methods, published in February in the New England Journal of Medicine, found no significant differences between the two methods.

In a 2009 paper in Stroke, Australian neurologist Anne Abbott, MD, reported that when people make lifestyle changes such as quitting smoking, controlling weight, and lowering cholesterol and blood pressure, the benefit for stroke protection exceeds that of the track record of surgery or stents. But her results were not universally heralded. Richard Cambria, MD, chief of vascular surgery at Massachusetts General Hospital, points to limitations with Dr. Abbott’s conclusions. He says his data show that about 40 percent of patients on medical therapy, including statins, saw blockages worsen.

The Mayo Clinic launched a study in December 2014 that may settle the issue. It will eventually enroll almost 2,500 people who will be randomly assigned for surgery, stenting, or medical treatment alone. Results won’t be available until around 2020. In the meantime, researchers are working to determine what makes some blockages more likely to cause strokes than others. There’s evidence that plaques encased in thick, fibrous caps are less likely to cause a stroke, says David Thaler, MD, chairman of the department of neurology at Tufts University School of Medicine.

What Patients Should Know

[dropcap]D[/dropcap]on’t have your carotid arteries screened without reason. If your doctor finds plaque, embrace medical management—statins, exercise, weight loss, and blood pressure control—regardless of whether you have a procedure, says James Meschia, MD, a Mayo Clinic neurologist and a principal investigator of the new study under way. If you’re considering a procedure, seek a second or third opinion—from different specialists. One study found that neurologists and stroke specialists were less enthusiastic about intervention than cardiologists and surgeons were.

Consider your own worry habits. “Once you tell [some patients] they have a blockage, you ruin their lives,” says Dr. White of Ochsner. “They worry every day about having a stroke. But other people say, ‘You know, doc, it’s not bothering me. I’ll call when I have a problem,’” Dr. White continues. “They’re better off with medical therapy.”

Which is what Martha Bowes wishes she had chosen. Fifteen years after her stroke, she can walk with a brace and a cane, but her left arm and hand are limp. She doesn’t fault anyone considering surgery but advises, “Understand the alternatives. I was given none.”