Here’s Why You’re Probably Overpaying for Medicine

Updated: Nov. 10, 2022

Does your prescription plan include an expensive “clawback”? Here's why that should worry you.

Eric Pusey has to bite his tongue when his pharmacy’s customers, thinking their insurance is getting them a good deal, cough up co-payments for generic medications that are far higher than the out-of-pocket costs.

Eric Pusey has to bite his tongue when his pharmacy’s customers, thinking their insurance is getting them a good deal, cough up co-payments for generic medications that are far higher than the out-of-pocket costs.

Pusey’s contracts with pharmacy benefit managers (PBMs)—the influential companies that administer prescription drug plans on behalf of insurers and large employers—bar him from volunteering details of their deals. In fact, for some generic medicines, co-pays do cost more than if a patient skipped insurance and paid for the drug directly. Pusey can tell people only if they ask—though they often don’t like his reply. “Some of them get fired up,” says Pusey, who owns the Medicap Pharmacy in Olyphant, Pennsylvania. “Some of them don’t believe what we’re telling them is accurate.”

The extra money—as little as $2 or as much as $30 a prescription—goes into the pockets of the PBMs. In the drug industry, these higher co-pays on cheap generics are called clawbacks, and they can mean millions of dollars for the PBMs on a highly marked-up drug.

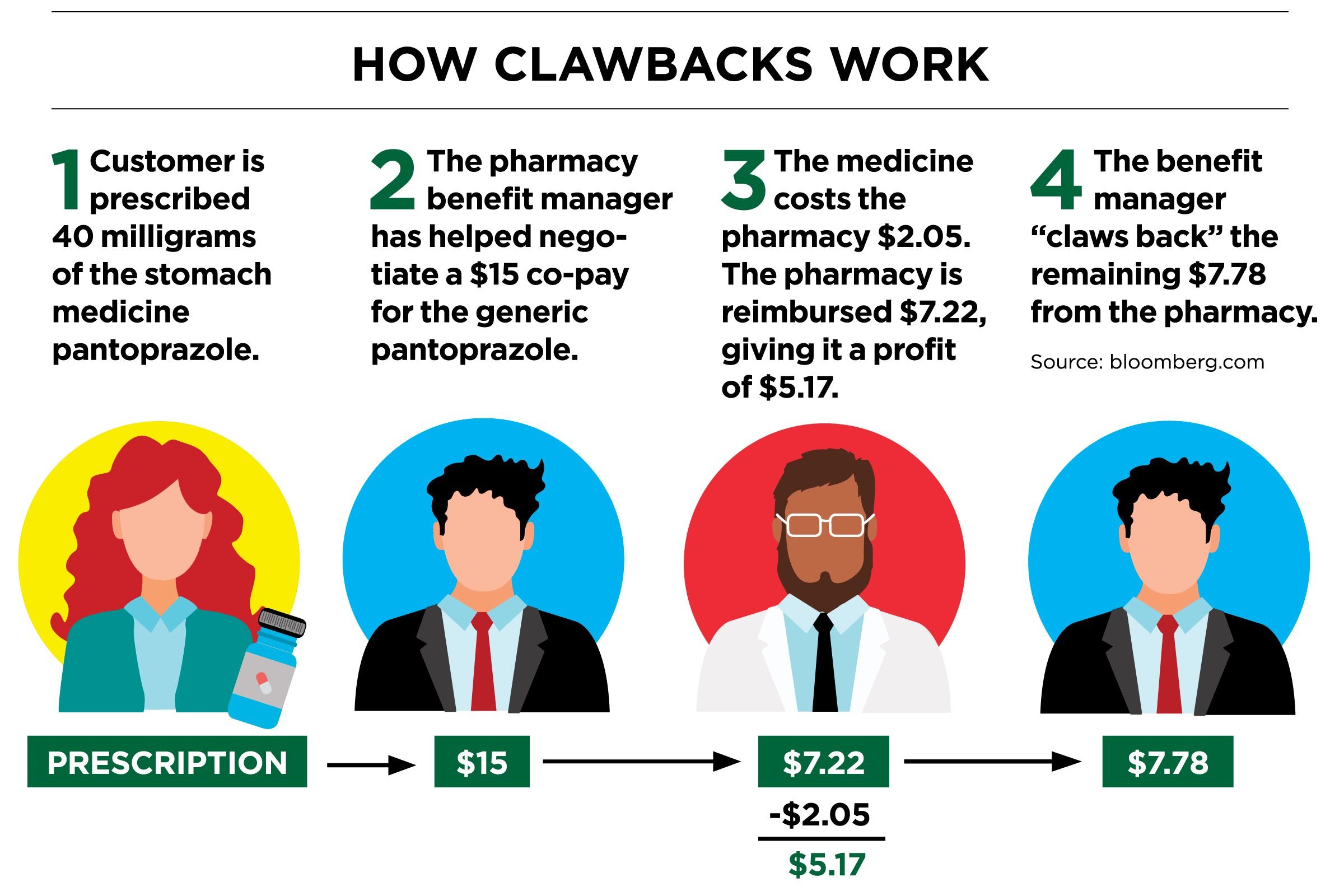

Here’s how clawbacks work: A patient goes to a pharmacy and pays a co-pay amount—perhaps $15—agreed to by the PBM and the insurers who hire it. The pharmacy gets reimbursed for the price of the drug, say $2, and a small profit. Then the benefit manager “claws back” the remainder. Most patients never realize that the cash price of the drug is cheaper than the co-pay.

“There’s this whole industry that most people don’t know about,” says Connecticut lawyer Craig Raabe, who represents people accusing two insurance companies and a PBM of defrauding them. Clawbacks are possible because benefit managers take advantage of an opaque market, says Susan Hayes, a consultant with Pharmacy Outcomes Specialists in Lake Zurich, Illinois. Only the PBMs know who pays what. Here are some more secrets your health insurance isn’t telling you.

For their part, benefit managers argue that they actually keep prices low, in part by negotiating rebates from drugmakers. That may be true in some cases, but clawbacks have prompted at least 16 lawsuits since October 2016, with accusations that include defrauding patients through racketeering, breach of contract, and violation of insurance laws.

For their part, benefit managers argue that they actually keep prices low, in part by negotiating rebates from drugmakers. That may be true in some cases, but clawbacks have prompted at least 16 lawsuits since October 2016, with accusations that include defrauding patients through racketeering, breach of contract, and violation of insurance laws.

The three largest PBMs in the United States—OptumRx (owned by UnitedHealth Group, Inc.), CVS Caremark (owned by CVS Health Corp.), and Express Scripts Holding Co.—process an estimated 70 to 85 percent of all the prescriptions in the country. A spokesperson for UnitedHealth Group, Inc., the target of a class action lawsuit alleging that OptumRx required network pharmacies to charge excessive fees, said, “We believe these lawsuits are without merit.” CVS Caremark and Express Scripts Holding Co. have claimed that they don’t use clawbacks, but in a lawsuit filed against CVS Health Corp., plaintiff Megan Schultz stated that the practice was part of both PBMs’ agreements with CVS pharmacies.

Many plans require pharmacists to collect payment when prescriptions are filled and prohibit them from waiving or reducing the amount. Pharmacies who contract with OptumRx, for instance, could be terminated for “actions detrimental to the provider network,” doing anything that “disparages” it, or trying to “steer” customers to other coverage or discounted plans, according to OptumRx’s 2016 provider manual.

“They’re usually take-it-or-leave-it contracts,” says Mel Brodsky, Executive Director of the Philadelphia Association of Retail Druggists. Independent pharmacies in particular fear getting removed from reimbursement networks, a potential death blow in smaller communities. A survey of 640 independent community pharmacists by the National Community Pharmacists Association found that 83 percent of the respondents see at least ten clawbacks a month.

“I’ve got three drugstores, so I see a lot of it,” David Spence, a Houston pharmacist, says. “We look at it as theft—a way for the PBMs to steal.”

Many legislatures are responding. At least 13 states have enacted laws prohibiting “gag clauses” that prevent pharmacists from telling customers about clawbacks; at least 22 additional states have similar laws pending.

In the meantime, when customers question their co-pay amounts, some pharmacists jump at the opportunity to explain how they can pay less. “Most don’t understand,” says Spence. “If their co-pay is high, then they care.”