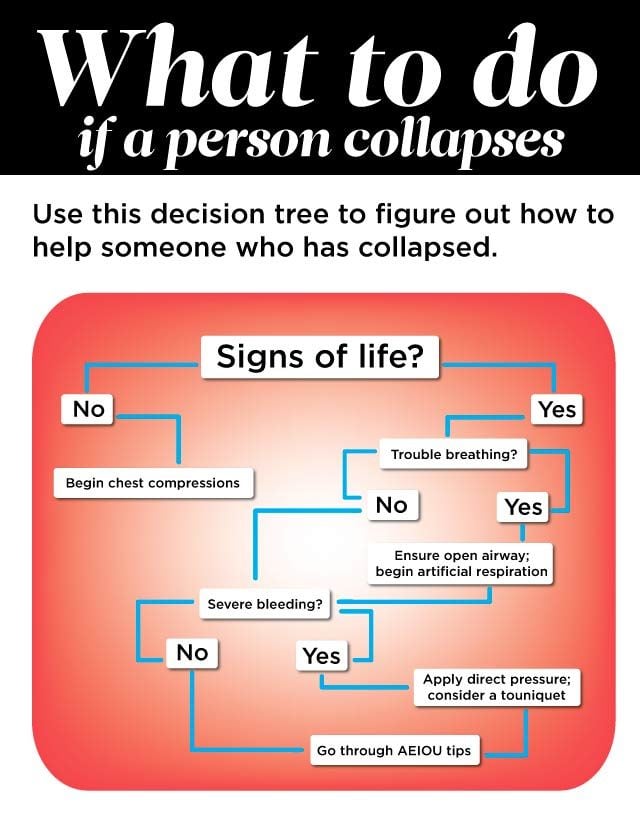

This Chart Shows Exactly What to Do if Someone Collapses

Updated: Nov. 17, 2017

First you need to evaluate a person's mental status and then follow these steps to keep them safe.

How to Recognize Altered Mental Status

If a person is unconscious or is acting inappropriately—maybe acting like someone who’s had a bit too much to drink—an altered mental status is obvious. But some times the clues can be more subtle and are likely to be missed unless you test for them. Do a screening exam whenever there’s a possibility of head injury or serious trauma—or if your suspicions are raised, even a little. The exam, called an alertness and orientation check, is quick and easy, and the results may surprise you. (Watch out for these clear signs that you’re about to faint.)

Step 1: Alertness Check

First note the victim’s alertness level. Is he anxious, groggy, or hard to wake up? Many emergency personnel use the acronym AVPU as a memory jog for evaluating alertness. With this acronym, they can communicate status to each other and also monitor whether the person’s getting better. Each letter corresponds to a level of alertness, going from better to worse.

Alert: The victim is awake and responds appropriately to questions and directions. (If the victim passes this level, this doesn’t mean there’s no altered mental status. Go to step 2—the orientation check—to make sure he’s completely alert.)

Voice: The victim is not alert but will acknowledge questions or commands, even if it’s with a mumble.

Pain: The victim won’t respond to voice commands but will respond to pain—i.e., he might grimace if pinched.

Unresponsive: The victim won’t respond to anything.

If the victim is alert, it’s time to get more detailed with an orientation check.

This is the scientific reason why healthy people faint.

Step 2: Orientation Check

The orientation check takes some cooperation and may require insistence on your part. The victim may be in pain or anxious and really not interested in answering your questions unless you can convince him that he must do so in order for you to help him. If he steadfastly refuses, that tells you you’re not going to be able to rely on his responses. On the other hand, even if the testing is normal, you’ll have a baseline to refer to in case something changes.

The four general questions to ask during the orientation check can be thought of as who, what, where, and when—otherwise known as person, event, place, and time. Ask the questions periodically to see if there’s been a change. If the initial checks are abnormal, if there’s been trauma, or if you’re really worried for whatever reason, you might check every fifteen minutes or so. If the results get worse, do a reassessment for causes you may have missed. (Of course, if the victim’s condition worsens, that’s all the more reason to try to get expert care as soon as possible.) If the results get better or at least don’t get worse, you may want to extend the time between testing to thirty minutes, then an hour, then longer.

- Person: Ask, “Who are you?” Insist that the victim give you his name. If you don’t know him, ask a friend or relative for verification or check his ID, if has one with him. If he knows you, ask, “Do you know who I am?” If he says yes, ask, “What’s my name?” Or ask, “Is this your friend? What’s her name?”

- Event: Ask, “What happened?” There’s no need to go into specifics. But he should know the basics—that he was hit in the head, fell, took medicine, had been drinking, has diabetes, or whatever the case might be.

- Place: Ask, “Where are you?” Again, a general answer—such as “In the park,” “At home,” or “In [the name of the city]”—will do.

- Time: Ask, “What day is it?” Or at least, “What month is it?” or “What year is it?”

If he gets any of the answers wrong, he has an altered mental status. If you’re not sure of the cause, it’s time to start looking.

Common Causes

The reason for altered mental status determines what should be done next. If the cause is not apparent, you may find clues while performing a quick physical exam.

It helps to know some of the causes and clues you’ll be looking for. The mnemonic AEIOU TIPS won’t cover every one of them, but it’s a way to jog your memory on many of the more common ones. (Some letters in this mnemonic can refer to more than one type of condition. Perhaps a better mnemonic would be AEIOU TTIPPS? An altered version for altered status?) Unless you’re absolutely certain of the reason, be a good detective and never make your final conclusion until you’ve finished the entire exam. There can be more than one cause, or there can be a contributing factor outside of the AEIOU TIPS.

Alcohol

Clues: The odor of alcohol; liquor bottles.

Treatment: If alcohol is the only reason for an altered mental status, the only treatment in the field is just to hope the victim can safely sleep it off. Be sure he’s on his side in case he vomits—and to keep his airway open. And remember: just because a victim has alcohol on his breath doesn’t mean there’s not another reason for the altered state.

Epilepsy (Seizure)

Clues: A medical alert bracelet or a card in the wallet. There are often bite marks on the tongue. (Find out what happened when a skydiver had a seizure while in mid-air.)

Treatment:

- Ensure an open airway. If the victim is lying down and not fully awake, turning him on his side will help the tongue stay clear of the back of the throat and will help any fluids, such as saliva or vomit, run out of the mouth and not down the windpipe.

- If you suspect the underlying cause, treat it. Give insulin or food, give antibiotics, stop the bleeding, and so on.

- Cover the victim. Hypothermia is a frequently forgotten risk, and it can happen in temperatures well above freezing.

- Let the victim sleep. If he is somewhat alert, sooner or later he’s going to want to sleep. That’s normal. Just make sure he continues to breathe without difficulty. Every hour or two, you can wake him to check his pupils and ask the orientation questions. But after a night or two, that’s going to get old. Consider gradually lengthening the times between checks, unless the evaluation suggests the victim is getting worse and therefore changes your treatment or evacuation plan. Letting him sleep can be healing.

Infection

Clues: Signs of illness before the mental status became altered (though there often aren’t any). Confusion in an elderly person can be the first sign of something as simple as a bladder infection. Fever is another clue, but even if it’s high, the skin can be cool and clammy—and the skin can be flushed and warm without fever.

Treatment: Depends on the infection type and severity. Quick diagnosis and treatment improves the chance of survival, so it’s essential to get expert care as soon as possible.

Overdose

Clues: Pill bottles; needle marks. Pinpoint pupils are a sign of opiate overdose—heroin, morphine, codeine, or certain other pain medicines. Large, dilated pupils are a clue that cocaine or sedatives might have been the cause. (Watch out for these signs that you’re taking too many prescriptions.)

Treatment: For a suspected opiate overdose, the drug naloxone now comes in a prefilled autoinjector and in a nasal inhaler. Some homeless shelters and family members of drug abusers may have it. Of course, a person can overdose on any medicine. The national poison control center’s number is 1-800-222-2222.

Uremia

Uremia is a buildup of toxins in the blood that happens when the kidneys aren’t working properly to flush them out.

Clues: A medical alert bracelet or wallet card; known kidney problems. People with chronic renal failure who have to get dialysis (an artificial way to flush the toxins) may have a large, firm tube implanted in an arm to provide easy needle access to a vein. Blood can be felt flowing through it.

Treatment: Barring expert dialysis, you can only treat a reversible underlying cause (such as poison, infection, or dehydration), if there is one, and hope the kidneys start refunctioning.

Trauma or Temperature

Clues to trauma: Evidence from a physical examination or finding the victim in a situation that indicates possible injury. Treatment depends on the nature of the trauma.

Clues to temperature: Evidence of hypothermia or hyperthermia.

Insulin

We’re talking diabetes here—the underlying problem being either too little or too much insulin. A person can have too much insulin (low blood sugar) if he’s injected himself with the wrong quantity, and he can have too little insulin (high blood sugar) if he’s forgotten to take his medication.

Clues: A medical alert bracelet or wallet card; some people might even have an insulin pump strapped to their bodies or their clothes that’s connected to an IV-type tube, which in turn is connected to a needle that’s inserted in the skin. Many a police officer (and doctor) has been fooled initially into thinking that a serious diabetic condition is nothing more than alcohol overindulgence, since both can cause agitation.

Treatment: Give the victim a little food or fruit juice. This increases blood sugar levels, helping someone with low blood sugar recover. It won’t help people with high blood sugar, but it’s unlikely to harm them. Unless you’re specially trained on properly giving insulin, there’s nothing to do in the field for someone with high blood sugar. (Never give anything orally unless you’re sure the victim is alert enough to swallow it. An option is to rub a little sugar, or the closest thing you have to something sweet, into the victim’s gums. Just beware of teeth and make sure the substance is nothing the victim could suck into his lungs.) If you’re lucky, an insulin-dependent diabetic might have a glucagon emergency kit. Glucagon is a hormone that can be injected to raise the blood sugar.

Poison or Psychiatric Illness

Clues to poison: Bottles; bad food; knowing the victim has eaten a plant.

Treatment for poison: Many times, as with alcohol overdose, all you can do is try to keep the person’s airway open and give time for the poison to wear off. Some poisons have antidotes, and that’s one of the reasons to call the national poison control center (1-800-222-2222) and 911 if you can. Never induce vomiting in someone who’s drowsy or lethargic; he could get vomit in his lungs.

Clues to psychiatric illness: Prescription bottles of psychiatric medications or a known history of mental illness. The person may be acting strange, hallucinating, or be extremely agitated.

Treatment: This can be complicated. Options include giving the person his medication if he needs it and trying to calm him down—or at least not excite him more. In the worst cases, you may need to remove yourself from the situation for your own safety.

The Survival Doctor’s Complete Handbook will take you step by step through the essentials of medical care during an emergency. Maybe you live alone in a rural area, or you just want to make sure you and your family are prepared to safely weather the next natural disaster. Whatever your situation and your health needs, The Survival Doctor’s Complete Handbook is your must-have medical resource.

The Survival Doctor’s Complete Handbook will take you step by step through the essentials of medical care during an emergency. Maybe you live alone in a rural area, or you just want to make sure you and your family are prepared to safely weather the next natural disaster. Whatever your situation and your health needs, The Survival Doctor’s Complete Handbook is your must-have medical resource.