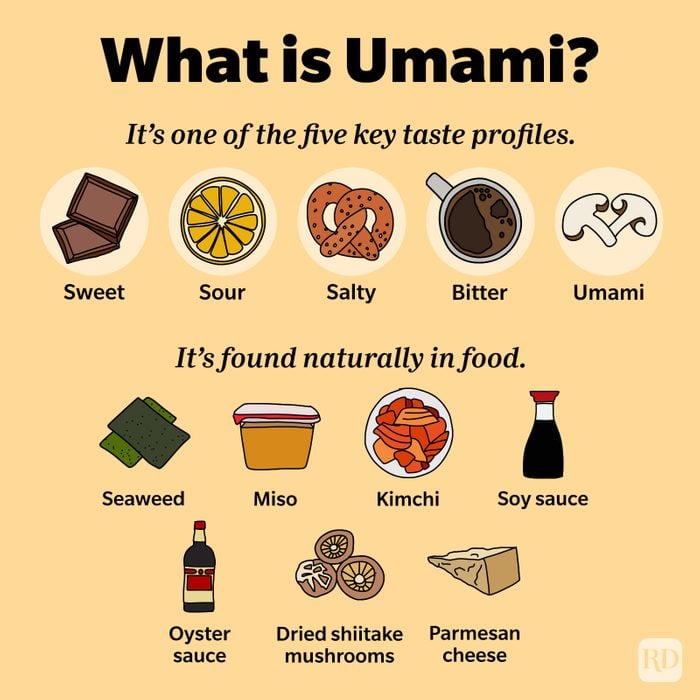

What is umami?

Since the beginning of time, food lovers have sought out unique flavors and perfected ways to introduce them to others, even at infancy. While babies can’t identify salty tastes until they’re about four months old, human taste buds are routinely replenished until the age of 30. And by the time we reach 40, our taste preferences are fully established. Yet despite spending decades tasting a full array of flavors, most of us barely remember there’s a fifth flavor profile. And when we do remember, we’re often scratching our heads, wondering, “What is umami?”

Most Western traditions identify four basic flavors: sweet, sour, salty, and bitter. You’ve known about those since you were young enough to blow your allowance on Sour Patch Kids. But Japanese traditions include another taste. This recently popularized fifth flavor is known as umami.

Read on to learn what umami is, what it tastes like, and where to find it in your favorite dishes. Then get more food trivia facts by reading up on what sashimi is and why truffles are so expensive.

What’s the history of umami?

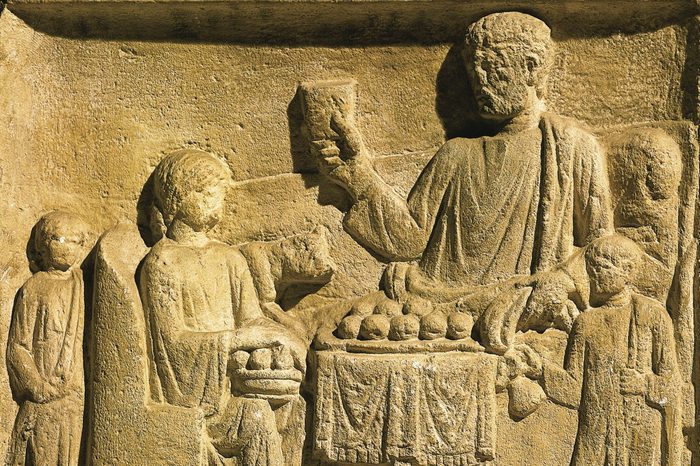

As far back as the Roman Empire, people have been cooking up ways to add a fishy, salty, savory flavor to their foods. Archeological excavations have revealed at least four different kinds of fish sauces used by Romans in pursuit of what we now call umami. The ancient Japanese tradition of making katsuobushi, a smoked and dried fish that’s an essential part of Japanese cuisine, has the same end goal. But though this mysterious flavor had been known for centuries, it wasn’t identified until 1908, when Japanese researcher Kikunae Ikeda isolated the taste.

Ikeda was trying to understand what gave his wife’s soups their unique flavor. Over the course of his experiments, he arrived at the specific taste molecule, pointing to the monosodium version of glutamate that was present in the brown kelp she used to flavor her stock. It was a familiar flavor, he thought, like meat, dried fish, and katsuobushi. Ikeda temporarily termed it “umami”—the Japanese word for “savoriness”—and the name stuck.

The finding might not have been groundbreaking at the time (it certainly wasn’t in the United States; Ikeda’s research wasn’t translated into English until 2002), but in hindsight, it was a major breakthrough. And it paved the way for umami to be recognized as a fifth taste.

What gives umami its flavor?

Just as you think of sugar when you think about sweetness, food experts think about glutamate when considering umami. Glutamate is an amino acid, a building block of protein. Two components come together to create umami: monosodium glutamate (MSG) and disodium inosinate (IMP). These don’t have much flavor on their own, but they enhance umami flavors in food.

Synthetically produced MSG is also called Aji-no-moto. It’s a white, flaky substance, and the MSG flavor is described as salty. Most purists don’t use it, but it can be convenient for those who have time or ingredient constraints.

What does umami taste like?

It’s one thing to answer “what is umami?” That’s an easy question. The harder question: What does umami taste like? Food scientists and researchers have long struggled to describe the exact taste, settling for descriptions like “savory,” “meaty,” and “broth-like.” Less of a struggle, however, has been determining umami’s effect on our sense of taste. For instance, many scientists believe that the umami flavor lingers longer on our taste buds than other flavors and that this quality makes umami more desirable. In fact, one study found that the addition of umami–bearing substances reduced the desire for saltiness in foods. Interestingly, too much umami can overshadow everything else and make a dish feel too salty—or even soapy!

Food historian and scholar Ken Albala has experimented with making katsuobushi from scratch to understand the flavor better. “Umami is actually several different chemicals, often acting in concert,” he says. Arriving at the perfect balance of flavor molecules creates the mysterious umami taste.

How do you cook with umami?

“The first step in creating an umami-rich dish is to use quality ingredients that have developed the glutamate and associated chemicals that contribute to umami,” says chef Eric Wynkoop, director of culinary instruction for Rouxbe online culinary school. Sure, you could make katsuobushi from scratch to make umami flavoring yourself, but it’s a labor-intensive dish, and you can buy the ingredient online and in most supermarkets. While ready-to-use synthetic Aji-no-moto is available, some folks do not like the MSG taste.

Once you’ve collected your ingredients, you can incorporate them into a wide variety of dishes. Our suggestion: Start by whipping up some Japanese-inspired dishes, which make use of a bunch of umami-rich foods. “Umami, whether from kombu [seaweed], MSG, or a combination of soy sauce, mirin, sake, and salt, is the foundational flavor profile of a lot of Japanese cuisine,” says Gil Asakawa a cultural consultant and chair of the Denver Takayama Sister Committee.

We’ve rounded up the foods that pack the greatest umami punch. As you browse, look for ways to combine them in your favorite dishes. Food traditions from cultures like India and Japan believe in layering flavors to create complex and more enjoyable dishes. “When umami is introduced through the layering of ingredients and in balance with the other tastes, the meal is perceived as having depth and providing satisfaction,” Wynkoop adds.

Seaweed

Glutamate content: 250 to 3,800 mg of glutamate per 100 grams

As Ikeda’s original source of experimentation, brown kelp, a type of seaweed, contains the glutamate that gives umami its characteristic flavor. Also known as kombu, edible seaweed’s glutamate content differs by variety, with ma konbu containing more than 3,000 milligrams of glutamate in a hundred grams of seaweed and rishiri-konbu containing 2,000 mg.

Dried seaweed is soaked briefly in warm water to release the umami-inducing flavors; the water is then used to make stock. It can be tricky to properly extract the umami without muddying the flavor. According to Elizabeth Andoh, author and Tokyo-based culinary instructor at Taste of Culture, you can delicately extract the best umami from kombu when the water is 60 degrees Fahrenheit. But if the water gets warmer than 85 degrees, it can become bitter and slimy.

Dried shiitake mushrooms

Glutamate content: 1,060 mg of glutamate per 100 grams

A popular additive in many Asian stir-fry dishes, dried shiitake mushrooms pack a lot of umami. And that’s not the case for all mushrooms. Truffles, for instance, only have between 60 and 80 milligrams of umami per 100 grams. Mushrooms are very easy to incorporate in any dish, are very forgiving toward novice cooks—they’re basically impossible to overcook—and offer a meaty taste and texture without the meat. It is believed that in Buddhist temples, where meat is not consumed, dashi (fish broth made from dried bonito) is created using dried shiitake mushrooms.

Soy sauce

Glutamate content: 400 to 1,700 mg of glutamate per 100 grams

Fermented products like soy sauce are loaded with umami and can really play up other flavors in a dish. It’s a go-to ingredient for stir-fries, a wonderful base for marinades, and an ever-present side for sushi and sashimi. Some people prefer a Korean soy sauce, while others may choose between Chinese or Japanese soy sauce or tamari. All are great, as they all offer lots of umami flavor.

Parmesan cheese

Glutamate content: 1,200 to 1,400 mg of glutamate per 100 grams

Strong-tasting cheeses like Parmesan—it can take anywhere from 18 to 36 months for the flavor to develop—are high in glutamate, which means lots of umami taste. It’s easy to work this ingredient into your favorite meals: Top pasta with freshly grated Parmesan, or sprinkle the cheese over chicken or a healthy salad. For more umami flavor, try Emmentaler, a Swiss cheese with 310 milligrams of glutamate. Or trade your American cheese for cheddar, which has 180 milligrams.

Oyster sauce

Glutamate content: 900 mg of glutamate per 100 grams

Foodies who love Asian cuisine will recognize this flavorful fermented sauce. Made from oysters, it’s rich and flavorful, imparting an umami taste to everything from stir-fried broccoli and eggplant to beef, chicken, and fish. Get to know about these foods which exactly taste like chicken.

Miso

Glutamate content: 100 mg of glutamate per 100 grams

Like soy sauce, seaweed, and wasabi, miso is a Japanese staple. It’s a food paste made from fermented soybeans and adds depth of flavor and a salty, savory taste to food. It’s the key ingredient in miso soup, naturally. But you can also use it in dressings, marinades, and even dishes like sweet potato casserole.

Kimchi

Glutamate content: 94 mg of glutamate per 100 grams

This Korean dish of salted and fermented cabbage and vegetables is another fantastic way to enjoy umami. Bonus: Because it’s high in digestive enzymes, it’s good for your gut. Kimchi is often included in the Banchan course—a collection of Korean side dishes—to stimulate the palette and encourage diners to create their own variations on the dishes they will enjoy. According to the Umami Information Center, Kimchi that’s made using napa cabbage yields the highest amount of glutamate. Next, find out what is burrata.

Sources:

- Ken Albala, food historian and scholar with University of the Pacific

- Elizabeth Andoh, author, and Tokyo-based culinary instructor at Taste of Culture

- Eric Wynkoop, director of culinary instruction for Rouxbe online culinary school

- Gil Asakawa, cultural consultant and chair of the Denver Takayama Sister Committee

- The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition: “Umami and the foods of classical antiquity”

- Polish Journal of Otolaryngology: “The umami taste: from discovery to clinical use”

- Food Reviews International: “What is umami?”

- The Journal of Nutrition: “Umami and food palatability”

- Flavour: “Seaweeds for umami flavour in the New Nordic Cuisine”

- BioMed Research International: “Umami the Fifth Basic Taste: History of Studies on Receptor Mechanisms and Role as a Food Flavor”