A dark cloud over pop culture

Pop culture revolves around the intersection of various societies: a little bit from here, a little bit from there. That’s entertainment. Adding diverse ingredients to the melting pot and stirring it up make the taste buds pop, but sometimes the meal can end up leaving the bitter aftertaste of cultural appropriation. That’s what happens when appreciation turns into exploitation: A dominant culture takes aspects of historically subjugated cultures and uses them for its own creative and commercial gain, without giving due credit, compensation, or respect to the creators of the original recipe. The term “cultural appropriation” was added to the Oxford English Dictionary in 2018, which defined it as “the unacknowledged or inappropriate adoption of the practices, customs, or aesthetics of one social or ethnic group by members of another (typically dominant) community or society.”

Of course, learning a definition and understanding what it actually means in real life are two very different things, especially when it comes to racially charged concepts. Here are a few examples from the entertainment world that you may not have realized were problematic—and will never look at the same way again. While you’re at it, read these essential books to understand more about race relations in America.

Al Jolson

One of the great early stars of cinema, Al Jolson is also one of the most problematic. From an era that gave us the 1915 racist classic The Birth of a Nation, a celebration of the Ku Klux Klan featuring White actors playing African American stereotypes while wearing blackface, the Lithuanian-born Jolson became an icon performing in blackface, perhaps most famously and infamously as he sang “My Mammy” in the 1927 film The Jazz Singer.

The problem with blackface, then and now, is in its history of usage in 19th-century minstrel shows. These were live variety engagements in which mostly White performers wore black makeup during skits in which they ridiculed Black people as being stupid and infantile. By appropriating aspects of Black culture and exaggerating and lampooning them, they presented racism as entertainment. In cinema, in theater, and on Halloween, blackface is just another reminder of how White America has long undervalued and subjugated Black people, making it always problematic, regardless of the intent of the White person wearing it.

In a 2019 Saturday Evening Post article, Ben Railton laid out the history of blackface in cinema, writing, “Perhaps most strikingly, the first prominent ‘talkie’ film, 1927’s The Jazz Singer, features Al Jolson as an entertainer who spends much of the film (including its triumphant finale) in blackface, cementing the central role of blackface to the evolution of American film across each of its foundational periods.” Racism is insidious—this is the psychology of how we learn prejudice.

Bo Derek in 10

These days, reality TV stars Kim Kardashian and Kylie Jenner field criticism for posting social media pictures of themselves wearing cornrows, a braided hairstyle that originated with Black women. It’s familiar outrage that began with the movie 10, Bo Derek’s 1979 breakout film in which she introduced the hairstyle to mainstream (White) audiences. It became a sensation that the White media dubbed “Bo Derek braids,” despite the fact that Black women had been wearing them for years. The Bo Derek hair craze set an ongoing double standard: The hairstyle that continues to cost Black women respect and jobs becomes stylish and cool when worn by trending non-Black women.

“So many facets of Black culture, both historically and contemporaneously, have become synonymous with mainstream American culture,” Keisha Brown, an associate history professor at Tennessee State University, told HuffPost in 2019. “A related issue at hand is the separation of Black culture from the peoples and history that created it. People embrace the hip or popular elements of Black culture, but not Black Americans.” Check out the accomplishments of these Black Americans you didn’t learn about in history class.

Cher’s “Half-Breed”

It’s hard to imagine a White artist today getting away with Cher’s number one single from 1973. It’s harder still to imagine one sexing up Native American fashion for the song’s video and not being subject to a barrage of criticism on social media. In Mary Dean and Al Capps’ composition, Cher sings about the cultural dilemma faced by a young woman who is half White and half Cherokee. Although it’s not really Cher’s story to tell (her father was Armenian, and her mother was mostly Western European and supposedly part Cherokee), the lyrics aren’t as problematic as the way the singer turned Native American cultural artifacts into a costume.

“Using women of color as props isn’t exactly new,” Boshemia magazine pointed out in a 2019 article that cited Gwen Stefani’s “Harajuki Girls” in addition to this Cher song. “Pop music has long lived on the commodification of other cultures without lifting them up. This has happened before. And it will happen again.” Here are more songs you didn’t know were actually pretty racist.

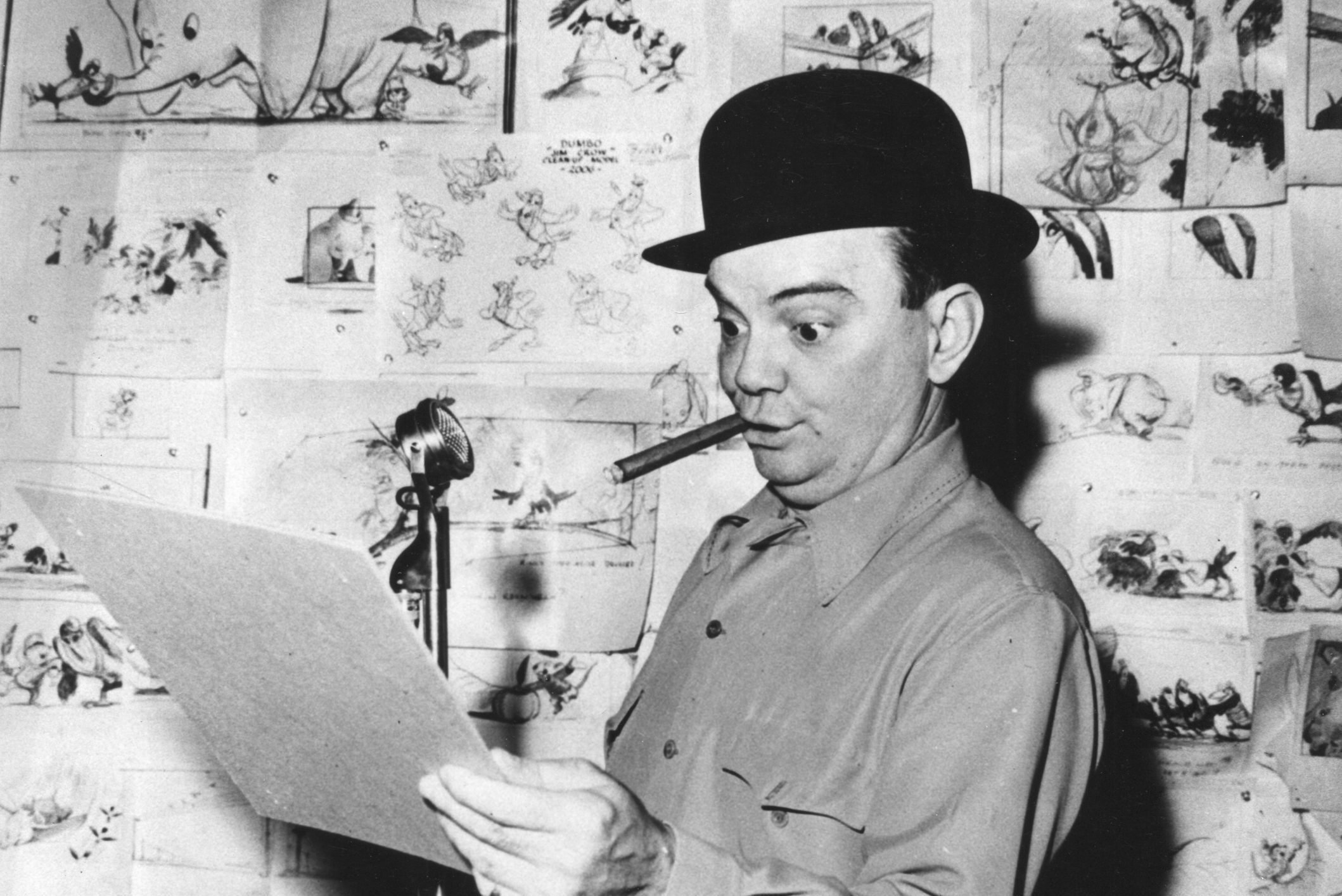

The crows in Dumbo

To many, the 1941 movie Dumbo is an animated Disney classic inextricably linked to childhood fantasy. It also teaches a valuable lesson about acceptance, overcoming obstacles, and turning lemons (big ears) into lemonade (wings). But about those crows… The film dives deep into cultural appropriation during those pivotal scenes in which the black crows help save the day for the titular flying elephant. “Today, many believe the crows to be racist caricatures of Black Americans for their use of ‘jive talk,'” Abby Monteil wrote for Insider in May 2020. “The lead crow is even named Jim Crow in an obvious reference to the racist Southern segregation laws that lasted until the mid-1960s. The character Jim Crow was also troublingly voiced by a White actor (Cliff Edwards).”

Disney+ added a disclaimer to the film warning of racist images, and Tim Burton’s 2019 live-action remake excised the black crows entirely. Although kids might miss the racist implications of the crows in the original, for aware adults, it bears the unmistakable sting of cultural appropriation as lampoon. Dumbo isn’t the only problematic Disney movie, and in fact, deeply rooted racism is the reason Splash Mountain is getting a long-overdue makeover.

I Dream of Jeannie

No aspect of Arabic culture has been appropriated by the West quite as vividly as the genie (aka “jinn”). In the 1992 animated Disney film Aladdin, the genie was male and voiced by Robin Williams. In the 2019 live-action Aladdin, he was played by Will Smith in blue face. Then there is the other well-known pop culture genie from the 1960s sitcom I Dream of Jeannie. The producers of the TV show didn’t even try to stay true to the genie’s dark roots, casting blond American actress Barbara Eden in the title role and making her a TV star.

“The show was full of stereotypes and it slowly filled viewers with negative versions of Arabs/Muslims,” Katherine Bullock, an Islamic Politics lecturer at the University of Toronto, wrote for The Conversation in 2019. “These standardized characterizations of Arab/Muslim men as barbaric, and women as submissive, highly sexualized harem girls, is on par with the worst offensive racial stereotypes. Unfortunately, while most producers no longer consider stereotypes of other ethnic groups as entertaining or acceptable, exotic and barbaric Arab/Muslims remain normalized.” Attitudes like this can lead to everyday acts of racism.

Iggy Azalea

There’s nothing wrong with White people rapping, and as Eminem has been proving for two decades now, some White rappers can do it quite well. Iggy Azalea is one of those rappers, but she ruined her reputation by failing the first test of hip-hop authenticity: She didn’t rap what she knows. Unlike Eminem, who never tried to mimic a Black vocal style, Azalea dropped every hint of her native Australian accent in favor of a so-called “blaccent” and various other trappings of Blackness, picking and choosing what aspects of Black culture to plunder without recognizing the struggle behind it.

“Is hip-hop only for Black people?” writer Jeff Chang asked in a 2014 Guardian article detailing Azalea’s dismissal of accusations of cultural appropriation. “It is an irrelevant question. Few Black hip-hop artists have ever made that argument. But to say that hip-hop begins as Black culture made by Black people is not just a statement of fact, it is an acknowledgment of the master key that opens the door for everyone, the way a clave unlocks a rhythm.” On a related note, did you know that these 12 everyday expressions are racist?

Celebrities in blackface on Halloween

It’s pretty cool that country star Jason Aldean is a fan of Lil Wayne. Instead of inviting the rapper to collaborate on a single, though, Aldean decided to dress up as him for Halloween in 2015. The problem was that he didn’t stop with fake dreadlocks. He also smeared on blackface in an attempt to capture Lil Wayne’s skin tone. Criticism followed, with Aldean offering a typical response to accusations of cultural appropriation: “In this day and age people are so sensitive that no matter what you do, somebody is going to make a big deal out of it,” he told Billboard in 2016. “Me doing that had zero malicious intent.”

His intentions were irrelevant, as have been the intentions of Ted Danson, The Real Housewives of New York‘s Luann de Lesseps, and other celebrities who have been criticized for wearing blackface. Before any of these people painted their faces black, they should have brushed up on Black history and taken the time to understand why this type of “dressing up” is so problematic. As discussed earlier, White minstrel-show performers appropriated the skin tone of Black people to mock them. “These displays depicted Black people as lazy, ignorant, cowardly, or hypersexual,” CNN’s Doug Criss wrote in 2019. “It was racist and offensive then and still is today.”

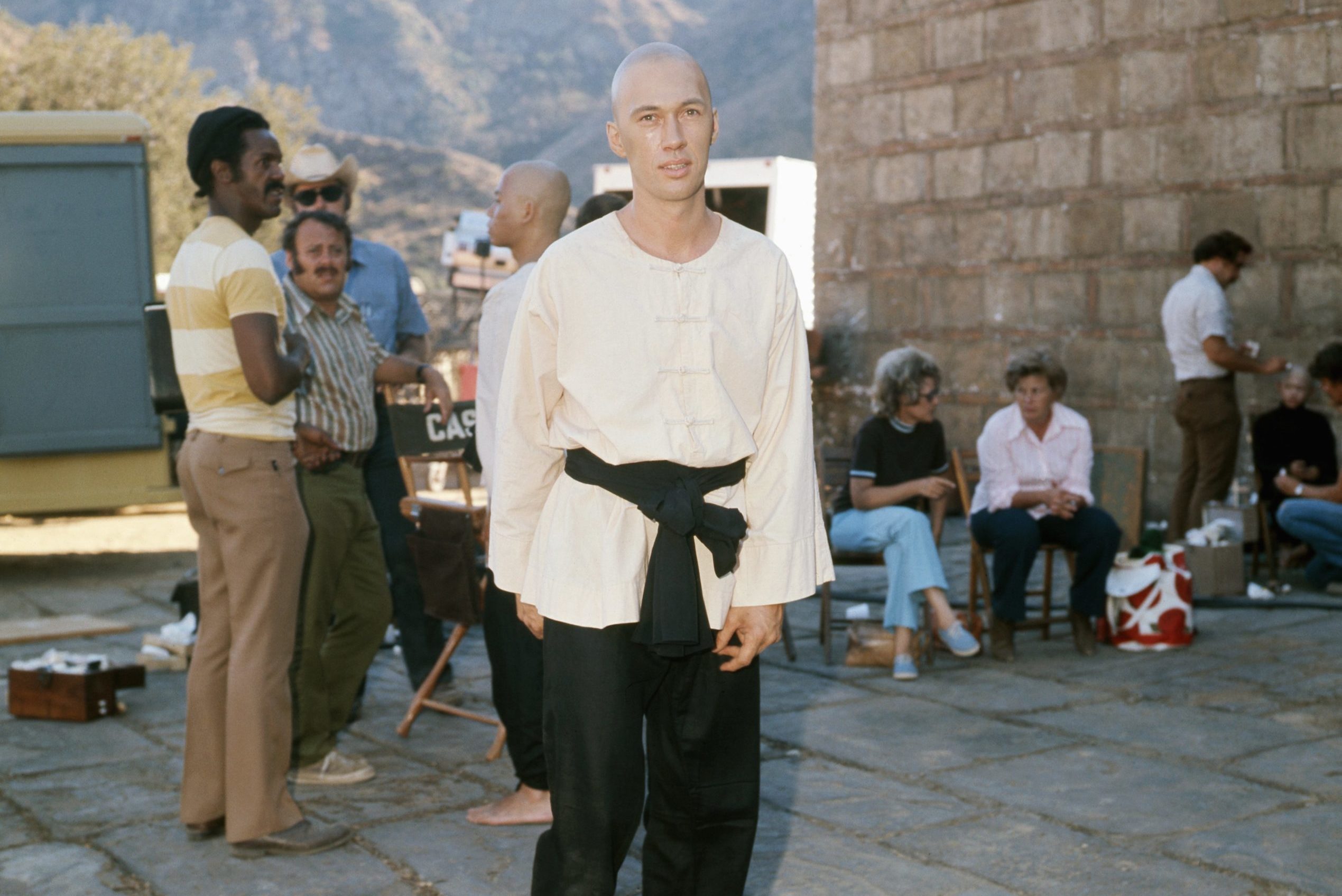

The Kung Fu TV series

Martial-arts movies were booming in the early ’70s, and someone had the excellent idea to create a TV series to capitalize on the Far East craze. But instead of casting Bruce Lee, then the biggest martial-arts star in the world, as the main character (half-Chinese, half-White orphan turned Shaolin master Kwai Chang Caine), the powers-that-be went with David Carradine, a White actor of Irish descent. “The very Caucasian-looking David Carradine is presented as a paragon of martial arts,” a Complex article pointed out in 2013. “There’s that, plus his character’s penchant for spouting weird fortune-cookie-style aphorisms like ‘Become who you are.’ All that, and, lest we forget: The whole idea for the show was straight jacked from Bruce Lee. So, what were we saying? Yeah. RACIST.”

It was but one example of a long Hollywood tradition of “yellowface,” where actors of Asian descent are passed over for Asian roles in favor of White actors, from German actress Luise Rainer winning an Oscar playing a Chinese woman in The Good Earth after producers passed over Asian American actress Anna May Wong, to Emma Stone playing a quarter-Chinese and quarter-Hawaiian character in the 2015 romantic comedy Aloha. American history has also been whitewashed. Expand your knowledge by learning about these amazing Asian Americans who made incredible contributions to the world.

La La Land

An Oscar-winning musical romance with two love stories: the one between leads Emma Stone and Ryan Gosling and the one between Gosling’s character, Sebastian Wilder, and jazz music. And therein lies the biggest problem with La La Land. It’s a movie that pivots around the greatest African American music form, yet Black characters are mostly window dressing. Black Grammy-winning pop star John Legend shows up here and there as Sebastian’s best friend who sells out to the commercial promise of pop, leaving La La Land‘s ardent jazz appreciation in Sebastian’s hands.

If his first love had been the Great American Songbook, there might have been no problem, but instead, the movie offers scenes of Sebastian “whitesplaining” the sacred status of jazz…to a Black character. “The White guy wants to preserve the Black roots of jazz while the Black guy is the sellout?” basketball legend Kareem Abdul-Jabbar wrote in The Hollywood Reporter in 2017. “This could be a deliberate ironic twist, but if it is, it’s a distasteful one for African Americans.”

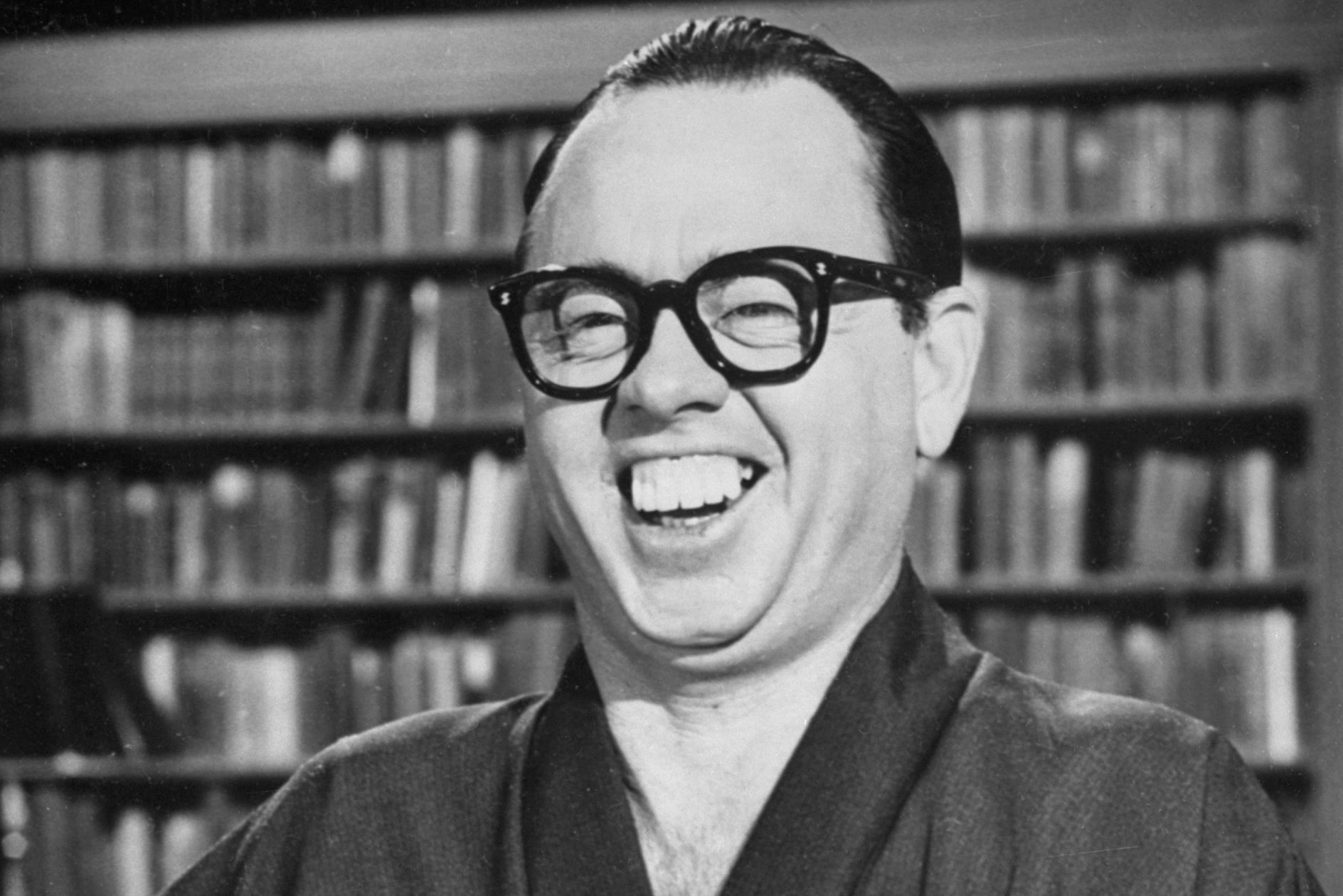

Mickey Rooney in Breakfast at Tiffany’s

There is so much wrong with the character of Mr. Yunioshi in the 1961 movie classic Breakfast at Tiffany’s. He’s not just the epitome of what then passed for the official Asian stereotype, but he’s presented as a cartoon buffoon and spends his screen time in the film flailing on the periphery, like some creepy and exotic alien. Even worse, he was played by Mickey Rooney, a White actor wearing yellowface and prosthetic teeth, contorting his features to appear more…Japanese? He was the kind of Japanese that only exists in Hollywood’s imagination, not in reality. A 1996 Berkeley University study summed it up perfectly as being “one of the most egregiously horrible ‘comic’ impersonations of an Asian in the history of movies.” Its unflattering cultural appropriation makes the Japanese stereotyping 42 years later in Lost in Translation seem documentary-caliber in comparison.

For more on this important issue, see our guide to the Fight Against Racism.