As strange as it sounds, the English alphabet had several more letters in the past few hundred years than it does today. Six more to be exact, including Ethel and Yogh (yup, those were the real names for “oi” sound, like in “coin,” and “kh” sound like in “Loch Ness Monster” respectively). Linguistics experts say that modern streamlining and the mixing of the cultures of Northern Europe are to blame for their loss.

“Some former letters had significance, as Eth and Ash are still used as part of the phonemic chart used for pronunciation,” says ESL professor Alix Hoechster, “but don’t expect to see them on your keyboard or use them in day-to-day life.” That’s because they’ve generally been phased out and replaced by letters that do double duty, either by already addressing the sounds in question or by making the desired sounds when combined with other standard, existing letters. This is why the letters on your keyboard aren’t in alphabetical order.

Anne Babson, an English instructor at Southeastern Louisiana University with a background in Late Medieval European languages, explains that the letters we no longer see gradually fell out of use as printing presses developed a type-setting system. “At first, Eth and Thorn were replaced with ‘Y’ in some typography and signage, so ‘Ye Olde English Shoppe’ would have been pronounced by contemporary readers as ‘the Old English Shop’ today,” she says. Fascinating stuff, right? And it doesn’t stop at easy advertising.

By the mid-1600s, the sound “th” was almost always represented typographically as it is today. But briefly, English contained a typographical letter called a “long s” from about the time of the Late Renaissance through the early 1800s—it looked almost like the letter “f” but was pronounced simply as “s.” “That’s why we have a frontispiece for the publication of Paradise Lost in the 1600s that looks like Paradife Lost,” Babson says.

If you’re wondering whether our current alphabet will keep shrinking, Babson suggests there’s no reason to worry about that anytime soon. “Standardized spelling makes it less likely for that to happen than when Middle English was turning into Modern English,” she says. “Most of our high school English teachers would roll over in their graves if ‘quick’ became permanently ‘quik.’ That said, it’s not impossible that we will simplify the orthography of many words the way the ‘drive thru’ has done.”

If you’re wondering about the letters we lost, you can pour one out for these tonight:

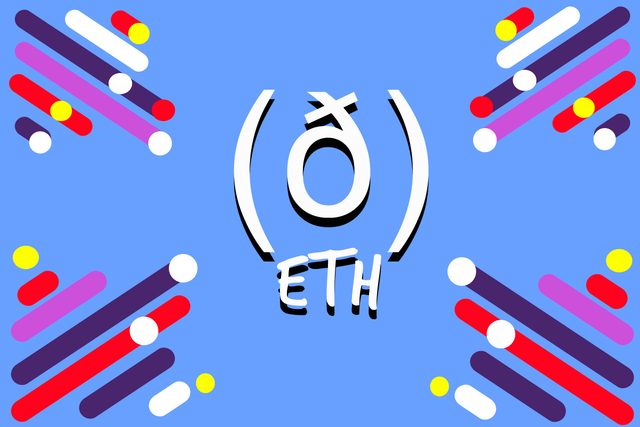

Eth (ð)

In its original form, eth was pronounced like the th sound in words like this, that or the, or then.

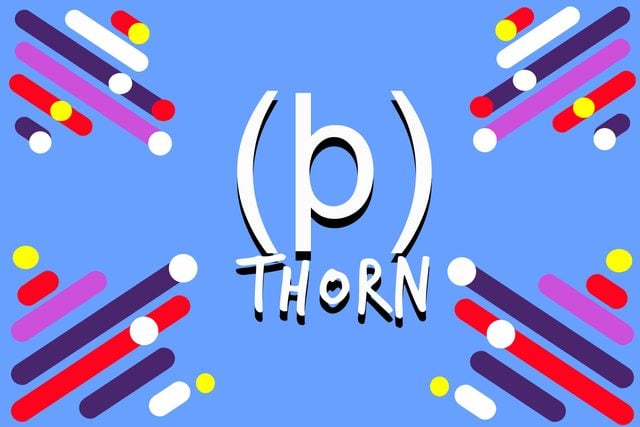

Thorn (þ)

Thorn was also pronounced with a th sound, but in a softer manner. Imagine using the th sound in the least aggressive way possible, with it rolling smoothly from behind your teeth. This is the surprising history behind why the alphabet is in the order that it is.

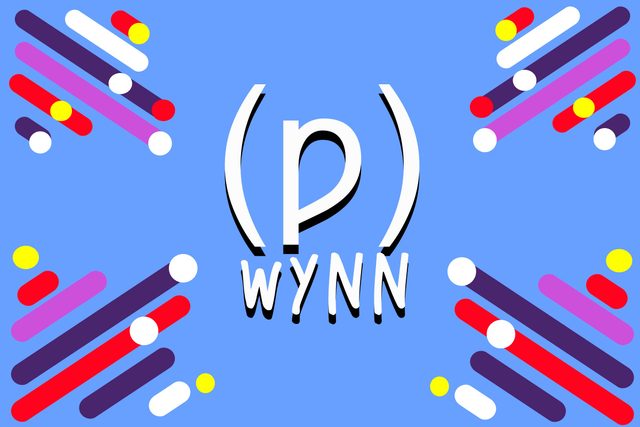

Wynn (ƿ)

This was the precursor to today’s uu; it lost favor when writers and printing presses started smushing two trendier u letters together.

Yogh (ȝ)

We can thank the Scots for this letter having existed, however briefly. Think of the ch sound in Loch Ness Monster, or the way you’d pronounce the ch in “challah bread.” The last letter added to the alphabet wasn’t actually “Z”.

Ash (æ)

Breaking news: This letter is still used in modern Danish. If you’re interested in partying with this antique, head straight to Denmark. Otherwise, just know that it was a short vowel sound in Old English, like the strange love child of a short a and a short e, like when you can’t tell if someone said “pat” or “pet.”

Ethel (œ)

Ethel was similar to Ash in that it was a strange hybrid but was pronounced like the “oi” in “join.” Next, read the fascinating facts about every letter in the alphabet.