Six Men Adventure Into a Very Dangerous Cave. Only Four Come Out.

Updated: Nov. 09, 2022

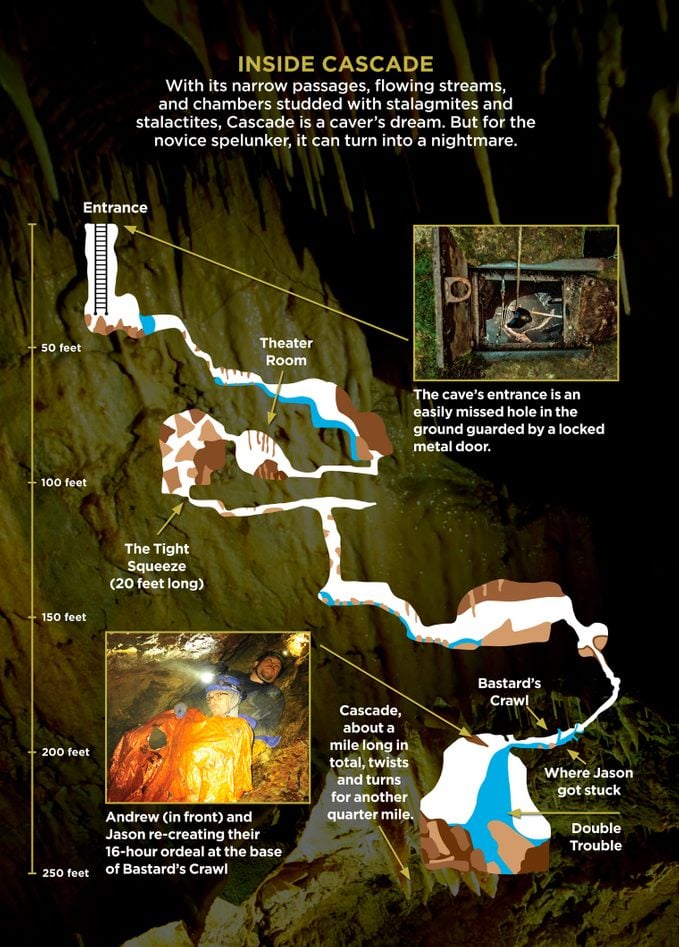

With its narrow passages, flowing streams, and chambers studded with stalagmites and stalactites, Cascade is a caver’s dream. But for the novice spelunker, it can turn into a nightmare.

The rain comes down steady and hard. Jason Storie hears it but is not worried as he prepares for a day of caving with five friends in a remote spot 80 miles northwest of his home in Duncan, on Canada’s Vancouver Island.

He is dressed for the wet weather—and for just about any other predicament: a T-shirt, then two sweatshirts, a pair of overalls, neoprene socks, a water-resistant jacket, and rubber boots. Under his arm, he proudly carries his new helmet and headlamp.

“Sleep in,” he whispers, bending down to kiss his wife, Caroline Storie.

“Be careful,” she says.

“Always.”

It’s 6 a.m. on December 5, 2015. A newcomer to the sport, Jason has gone caving only four times. This will be his toughest outing yet: a cave called Cascade. It’s dangerous enough that the entry is blocked by a locked metal door to keep the casual spelunker out; the key can be obtained only after everyone in the caving party signs a waiver. About a mile long and 338 feet deep, Cascade is full of turns and barely passable tight squeezes—a claustrophobe’s nightmare. Check out some more forbidden places around the world no one can visit.

Jason is the outlier among the group, with the least experience and, at 43, older by a decade or more. A stocky father of two toddlers, he is a university drama graduate turned entrepreneur, the owner of a window-washing company. It was his friend Andrew Munoz, 33, who introduced him to the sport. Unlike Jason, Andrew is an expert caver—a former caving guide, actually—and a wiry paramedic who would know what to do if something were to go wrong.

Jason, Andrew, and two more friends—Adam Shepherd, also a paramedic, and Zac Zorisky, a chef and volunteer firefighter—drive through the heavy rain to the parking lot of a log-cabin candy store in Port Alberni, where they get the key to that metal door. There they meet up with Matt Watson and Arthur

Taylor, both computer programmers.

The six men drive up an unmarked trail for half a mile before parking in a clearing to take inventory: Ropes, harnesses, and carabiners? Check. Two bags that contain a small gas-fueled Jetboil stove, food, water, and a first aid kit; and a Mylar “space” blanket that resembles aluminum foil? Check, check, and check.

They hike a bit before coming to the door, which sits in the ground—you’d miss it if you weren’t looking for it. It’s 10 a.m. They pull the door open and climb 30 feet down a rickety aluminum ladder into the black, each of them anchored with carabiners to a rope. The last one in locks the door behind him and ties the key to the bottom of the ladder. It is damp and chilly, about 41 degrees. With their way illuminated by headlamps, they walk down a narrow passage studded with jagged boulders. The silence is broken by a drip-drip-drip from above. Soon the drip turns into a light but steady flow, and they are wading in water up to their ankles, then to their shins.

“Everyone OK?” Andrew, the de facto leader of the group, calls out.

“Yeah,” comes the reply.

“Yup.”

“Me too.”

About 45 minutes in, Adam announces he can’t go any farther; his back, injured a few weeks earlier, is twinging. The constant hunching over has taken its toll. Matt escorts him to the entrance to let him out. He closes and locks it again, and then rejoins his four waiting friends.

For the next 90 minutes, they are explorers, taking their time as they crawl, stride, and slide through the cave’s two very different environments: either pipelike passages barely big enough to fit a grown man or chambers that are like the nave of a church, big but not overwhelming. Wherever they go, they try to stay within a hundred feet from the first person to the last, congregating in the chambers between the more challenging crawls and climbs.

Jason is in awe of his surroundings. Andrew once told him, “There are over a thousand caves and tunnels on Vancouver Island, and it’s never the same.” Cascade is like nothing he’s seen before.

Soon they approach one of the features that make the cave unique: a narrow passage not big enough to stand up in that leads into a short, tight downhill.

This has a name: Bastard’s Crawl. Four streams meet here, and indeed, the water is flowing more quickly.

“Crab-walk!” Andrew calls.

Once they emerge from Bastard’s Crawl, they approach the top of a waterfall called Double Trouble—so named because a jutting rock splits the stream in two. They set up their ropes to rappel 50 feet. Boots and gloved hands claw for leverage on slippery ledges. The water gushes on either side of the rock formation, landing at the bottom in a spray of bubbles. There’s a reason this cave is called Cascade.

As Jason descends, his heart is beating so hard, it feels as if it will jump out of his chest. You wanted a harder challenge, he thinks. You got it.

A few minutes beyond Double Trouble, they stop for a quick bite. It’s just before 1 p.m., and they’ve been in the cave for three hours. Andrew fires up the Jetboil to make beef and chicken stew with rice. After their 20-minute lunch, the five head out again, sliding and crawling their way down toward the cave’s end, less than a quarter mile away. But they get only 300 feet when Zac begins shivering violently. Although the temperature hasn’t changed, the cold inside a cave can hit unexpectedly. The five decide to turn back together.

They start to retrace their route. First Matt goes, then Arthur, then Jason, Zac, and Andrew. The sound of rushing water grows louder. There is more mud than there was on the way down a few hours earlier, and it sticks heavily to their heels. Plus, they are now climbing up, so it’s taking much longer to return than it did to come down. “Careful!” one of the cavers up front yells to those behind.

As it nears 2:15 p.m., the cavers approach Double Trouble. The sound of the water has turned into a roar. What had before been a gushing but manageable flow is now a churning, angry white froth. How could this happen so quickly? Jason wonders. Is it runoff from the rain?

Matt hooks the rope that was left attached at the top of Double Trouble to his harness and starts hauling himself up. The journey is not long, maybe 50 feet, but it’s tough, precise work: hoisting one leg to find a tiny, wet shelf in the rock wall; then a gloved hand; then the other leg. Once he has climbed to the top, he throws the rope down, and Arthur follows suit, then Jason. At the top, Jason gets on his stomach to pull himself up the incline of Bastard’s Crawl. The water, deeper than before, smashes into his face as he powers through it. God, it’s cold!

Finally emerging through the opening and into the next tight passage, he pauses, puzzled, because it splits into two. He can’t see the two cavers ahead of him and is nervous about waiting at the top because there is really only room in this spot for one person at a time. I’ll just go back down and ask, he decides.

He carefully crab-walks about 15 feet when the streaming water suddenly sweeps him onto his back, submerging him. He feels the pressure of more water building up behind him. If he doesn’t get out of the crawl fast, the merciless surge of water will pop him out like a champagne cork, over Double Trouble and onto the rocks below. But he can’t move—his boot is stuck between two rock shelves.

Lying on his back with the water rushing over him, he tries to call for help, but instead he gasps frantically for air. It has been about five minutes. It feels like forever. Images of his family flash before him, like a mental photo album he tries to hold on to: Caroline, whom he has been married to for 16 years and who had warned him to be careful that morning; Jack, five, who loves airplanes; and three-year-old Poppy, his princess.

Zac, having followed Jason up, is now atop Double Trouble. He shouts down to Andrew, “Jason’s in trouble!”

Andrew clambers up behind Zac and goes to the bottom of the crawl. “Head up, Jase,” he yells to his friend. He can barely see his friend’s face through all the water. Jason is only a couple of feet away, but he’s in such a precarious position and in such a tight space, Andrew can’t easily pull him out. “Keep on coming, dude. Toward me! Head up!” Jason is flailing. “Place your feet against me! Lift your butt up and float. C’mon, Jase!”

Jason’s gloved hands emerge from the water, then his wet face. He is gulping air as if he has hiccups. “My leg’s caught.” Jason doesn’t recognize his own voice because it comes out so slurred and slow, as if he’d suffered a stroke. He tries to dislodge his boot. It won’t budge.

“It’s OK, dude,” Andrew says, reaching into the rushing water and fishing around for the stuck boot. He grasps something solid. “Is this it?”

“Yeah.”

“Well, we got ourselves in a jam. OK, we’ll do this together.”

Twenty minutes after getting stuck, Jason emerges from Bastard’s Crawl like a baby being birthed, wet through, eyes shut tight, and gasping. Andrew settles him on a narrow ledge inches above the water. Jason, his eyes now wide open and looking bewildered, knows he had a close escape.

“You’re OK,” Andrew says, grasping his shoulders. “Zac, stay with Jason while I get the supply bags up ahead.”

It takes him about 15 minutes. On his return, Andrew tells Zac the water is still rising, so he should join Matt and Arthur just beyond Bastard’s Crawl. “I have to get Jason warmed up before we try to get out,” he says. “If we don’t catch up to you in 30 minutes, notify Search and Rescue.”

Unspoken is Andrew’s fear that Jason is turning hypothermic, so cold that he has stopped shivering. Andrew wraps his friend in the Mylar blanket and fires up the Jetboil. He warms Jason by pouring hot water down his clothes. As he does so, Jason’s color starts returning to normal.

“Welcome back, buddy. Do you feel ready to get out of here?”

With an hour hike to the entrance, they start to climb, inundated by water. They’re fighting it—or it’s fighting them, crushing them, pushing them back.

When they finally near the top of the crawl, there are barely four inches of air left between the water and the ceiling, not enough for them to keep their heads up to breathe.

“It’s too high!” Andrew calls. “Turn back!”

Jason spots a ledge; although the wall is at an awkward 45-degree angle, there is room enough for the two of them. Andrew perches in front of Jason to take the brunt of the spray from the water, his legs uncomfortably braced against a ledge on the other side of the waterfall.

The water keeps rising, almost to the ledge, and its sheer force and fury cause a wind to come up. Both men know that caves have their own microclimates, and with nowhere to go, the wind whistles and keens. It is 6 p.m. They are about 200 feet underground at this point. Zac left them three hours ago. They huddle together under a blanket. The Jetboil is out of fuel.

“If we don’t get out of here, our wives will kill us!” Jason says drily.

Conserving the batteries in their headlamps, they sit mostly in the dark, which makes them forget what a tight space they are in.

Jason draws on his theatrical training, forcing his breathing to slow down and move through his diaphragm and up to the tip of his skull. Trying to warm his face, he pulls his sweatshirt up over his nose. He thinks about his family and wonders how much life insurance coverage he has.

Andrew silently recites a mantra based on a passage from the science fiction novel Dune: Fear is the mind killer. Fear is the little black death that brings total oblivion. I will let the fear pass through me, and when the fear is gone, only I will remain.

There is no sign of rescuers. Did the other three even make it out? Maybe they’re lying on the other side of Bastard’s Crawl, blocked by water and injured.

Or dead.

What the two men don’t know is that their friends did make it out. They called for help, and at around 9 p.m., members of the Ground and Cave Search and Rescue squads arrived on the scene and entered the cave. But the water level, as well as its ferocity, forced them to retreat. They would have to try again later.

The hours pass. Jason and Andrew don’t dare to move for fear of slipping. They doze off, then jerk themselves awake, and they check in with each other every 20 minutes or so.

“You still with me?” Andrew asks.

“Yup. You still good?”

“Yup.”

Every once in a while, one of them turns on his headlamp to scan the water level. Around 5 a.m., it seems to be receding. “Let’s wait for a bit and see,” Andrew says.

An hour later, the water level has gone down enough that they can keep their heads above water and try an escape. Stiff from sitting in one position for 12 hours, they slowly unfold their bodies. Jason screams in pain. A muscle in his groin is strained, but he is determined not to let it stop him.

Getting on all fours and through Bastard’s Crawl—nothing else matters but that. Still, each time Jason moves a leg, he cries out. “You can do this,” Andrew exhorts. Then they are through.

Over the next 90 minutes, they make their way toward the entrance, at times in chest-high water. Now, in a passage that is high enough for them to walk upright, Jason sees something flicker in the distance.

“Lights! I see lights!” Jason plows ahead. Soon they hear voices.

“Hey,” they call out. “We’re here!”

“Andrew? Jason?” It’s one of the rescuers.

For the first time since entering the cave, over 20 hours earlier, Jason’s emotions get to him and tears trickle down his cheeks. “We made it.”

Next, read about the most gorgeous sea caves in the world.