Uniting in the Face of Deadly Blizzards and Tragedy, Buffalo, New York, Is the Nicest Place in America

Updated: Mar. 13, 2024

Despite natural disasters, shooting tragedies and Damar Hamlin's near-death experience, Buffalo's community is stronger than ever

By the time the blizzard hit Buffalo, Craig Elston was the last barber left in his shop. Inside were warmth, safety and a well-stocked candy machine. Outside was a swirling mess of some of the worst that winter can dish out.

“It was like nothing I’ve ever seen,” Elston says. “Eighty-mile-an-hour winds. If you went outside, it would just knock you over.”

It was Dec. 23, 2022. The day had dawned mild, but by midday, temperatures had plunged, winds were blasting and snow was piling up fast. News reports grew urgent: Get off the roads. Find shelter fast.

Soon neighbors were knocking, desperate for warmth and safety. Over the course of the next five brutally cold days, Elston would help dozens stay warm, fed and alive—at least 40 people, maybe more, he figures.

It wasn’t fun or easy. “One dude flooded the toilet three times,” Elston says. But it had to be done, he adds: “Those 40 people could have died out there.”

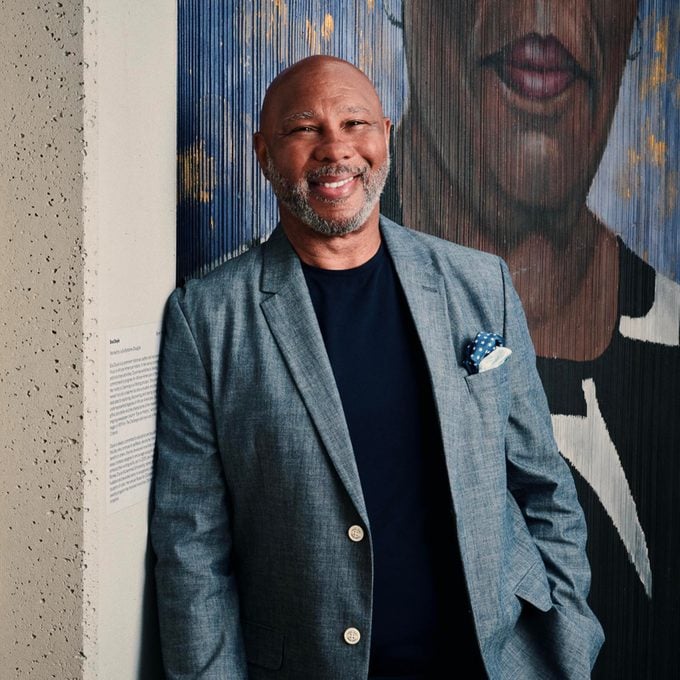

Craig Elston is 38. He grew up in Buffalo, where he runs the C&C Cutz barbershop on Fillmore Avenue. It’s the kind of neighborhood where “you can get a gun like it was a loaf of bread,” says Elston’s friend Dwayne Ferguson.

But it’s also full of hardworking people of all kinds, including new immigrants and families that have lived there for generations. Challenges are nothing new for Buffalo residents like these, says Ferguson. “Every day is a blizzard,” he says. “It just depends on how you deal with it.”

Dealing with it has become Buffalo’s specialty. Not long ago, the city was one of America’s most prosperous. More recently, Buffalo has suffered through some of the nation’s most painful losing streaks. Long before its football team was infamously losing Super Bowls, the Great Lakes economy was losing jobs and industries. And in 2022, Buffalo witnessed one of the nation’s most horrific mass shootings, with 10 people killed at the Tops supermarket just a couple of miles from Elston’s shop. A final, crushing blow: On the last day of the year, right on the blizzard’s heels, a house fire on Dartmouth Avenue took the lives of five children and their grandmother.

But for all the troubles, one thing has never changed, says Ferguson. “Buffalo is a city of good neighbors,” he says. “You have a lot of good stuff going on. You just have to know who to ask.”

And on that deadly December day, as the biggest blizzard since 1977 rolled in, Elston realized that it was his turn to help. So he went to TikTok to open his doors to Buffalo.

“Anybody out there that’s stuck, do not stay in your car, man,” Elston announced in his video. “The barbershop here welcomes you. Get some heat, get some electricity, charge your phone, get in contact with your family.”

The historic storm would eventually kill 47 people in and around the city, raging for days and dumping over 50 inches of snow. Temperatures dropped below zero. People died while stranded in cars or walking the streets. One was a friend of Ferguson’s: “He fell down and couldn’t make it home.”

Elston credits his old coach, Bill Russell, from his basketball team at Buffalo’s Riverside High School, for inspiring him to step up when his neighbors needed him.

“He’s the reason I opened the doors,” says Elston. “The real key to success is to pour yourself into the people around you. That’s what Coach taught me.”

The coach himself weathered the storm in his home, where he was snowed in for a week. Only later did he learn what his former player had done, and why.

“Craig has been amazing. I’m proud to know him,” Russell says. “I’m not one bit surprised that he stepped up.”

Also unsurprised was the Reader’s Digest reader who nominated New York’s second-largest city as one of America’s Nicest Places.

“That is so Buffalo,” said Kathleen Miller when she heard Elston’s tale. “The thing that has made me a huge Buffalo fan is the people … they’ll do anything for you, but they will not brag about it.”

“That could’ve been me”

Miller was born in Oregon, but after three decades in Buffalo, she feels like a native. Snow is a fact of life in western New York, but Miller, now a retired business executive, didn’t experience her first true blizzard until 2006. It trapped her in her office downtown, giving her a front-row seat to see the Buffalo way in action.

“Everybody abandoned their cars in the streets. There were all these strangers going around helping strangers,” she says. “In the garage under my office, there was a woman delivering a baby. Ambulances couldn’t get in,but there were 12 people around this woman, and they delivered the baby that night.”

That was her first encounter with the Buffalo way. “It really didn’t matter who you were,” she says. “If you needed help, you were going to get it.”

Krista Lipczynski, another area resident, says the troubles that have hit Buffalo breed a certain understanding: We’re all in this together.

“Buffalo really got it bad in the last few years, between the weather and the shootings and all of that,” Lipczynski says. “The people who died on the side of the road … it didn’t matter if you were driving a brand-new pickup or an old beater. You think, That could’ve been me. And it might be me next time.”

Lipczynski has gotten to know the region’s best side through her work with Kindness Buffalo, a volunteer group that organizes fundraisers and commits random acts of kindness like bringing gift cards to people in the hospital. Its efforts bring some sunshine to a region that gets just nine hours of daylight in the depths of winter.

“It’s hard to live here. It’s dark. Seasonal depression is a real thing,” says Lipczynski. “But I couldn’t imagine living anywhere else.”

Buffalo sits on the edge of Lake Erie, about 20 miles south of Niagara Falls, near the Canadian border. Some of its roads run atop the ancient paths of the Iroquois people who lived here for centuries before Europeans arrived. Once a capital of shipping and manufacturing, Buffalo has struggled economically in recent decades.

In 1950 the city’s population was almost 600,000 people; by 1990 it was down to just over 300,000. That was the same year that Buffalo’s beloved football team, the Bills, lost the first of four Super Bowls in a row. The one-time Great Lakes powerhouse had become best known for falling snow and falling short.

But the years since have shown that Buffalo has a way of bouncing back, and it starts with neighbors helping neighbors, says Ferguson. “What we ask is ‘What can I do for you right now?’ ” he says. “I’m a human like you. I’m here with you. It’s about meeting that moment.”

That attitude has helped the city endure. Buffalo’s metro region remains home to more than a million people. Its skilled workforce still draws employers and jobs. It’s spacious and green, with an affordable cost of living. Manufacturing has dwindled, but Buffalo’s service economy has grown, anchored by universities and health care. It remains a magnet for students and tourists.

And the entire region is a hotbed of arts, culture, winter sports and water sports. Buffalo winters may be dark and cold, but sparkling summer days on the shores of Lake Erie are hard to beat.

Among Buffalo’s other cultural calling cards: the stunning cathedral called Our Lady of Victory, the bustling museum district of Canalside and the annual chicken-eating festival that celebrates the city’s signature food, Buffalo wings.

And, of course, there’s the football team. “Everybody here is a Bills fan,” says Lipczynski.

“You have to be,” says Miller, who moved to Buffalo just in time to see the Bills lose the 1993 Super Bowl to the Dallas Cowboys. “I felt like I was at a wake,” she recalls. “Black, White, poor, wealthy, everybody just bucked each other up and said, ‘Our time is going to come.’ ”

The storm arrives

The first blasts of snow hit Buffalo around 10 a.m. on a Friday; soon the blizzard gripped the region like a claw. Temperatures plunged. Roads became impassible. Emergency crews rescued 65 people before abandoning the effort as too dangerous. At one point, police logged 1,000 unanswered calls for help. More than 30,000 people lost power.

Much of Craig Elston’s neighborhood lost power too, but not his barbershop. The first person to knock on his door was a Middle Eastern neighbor who barely spoke English. Elston didn’t need a translator to see the trouble.

“He had frostbite on his fingers, on his toes—it was really bad,” recalls Elston.

Not far away, Miller was about to get her own reminder of the Buffalo way. She lives on 100 acres outside the city, raising horses and cattle, and as the storm blew in, she expected to be cut off from her barns and animals. The handyman who typically helps her had been hospitalized with a bad burn, and she didn’t expect to see him. So she gave her animals a double feeding, crossed her fingers and got ready for bed.

“All of a sudden my doorbell rings, and there he stands,” she recalls. “I said, ‘What are you doing?’ He said, ‘I’m getting you out.’ So I gave him some beer and cookies. It took him 30 minutes to get to the horse barn. Then he took my tractor and cleared out two of my neighbors. That is Buffalo.”

Across the region, as emergency vehicles bogged down, other residents stepped up. One was Jay Withey, who broke into a school to shelter himself and 20 other stranded motorists. Before leaving, he wrote a polite note on a whiteboard: “I’m terribly sorry about breaking the school window. I had to do it to save everyone.”

Another was Sha’Kyra Aughtry, who saved a 64-year-old autistic man from freezing outside her home. “I said, ‘Listen, we got to go out and get this guy,’ she told People. “This could be your mom, this could be my dad, this could be anybody.”

And then there were Alexander and Andrea Campagna, who shared Christmas Eve with nine Korean tourists who had been headed for Niagara Falls. Other stranded drivers stayed in a local Target; about 100 more stayed at the Alabama Hotel in the nearby town of Basom.

Meanwhile, as squads of volunteer snowmobilers prowled the streets, Facebook groups sent people to safe havens like Elston’s barbershop. For five days, dozens came and went from C&C Cutz, including a family with two children.

“I had everybody in here,” Elston recalls. “African people, Arabic people, Hispanic people.”

Some stayed to sleep, wrapping themselves in barber capes; some stopped just to charge phones; some came and went as they searched the neighborhood for food or friends in need. It got crowded and sometimes feisty, with worried, hungry people chattering at each other in different languages.

“People couldn’t understand each other,” Elston says. “I broke up a lot of fights. It was a headache. It wasn’t peaches and cream.”

Along the way, barber chairs got broken, the candy machine got raided and the front door was knocked off its hinges. But when it was all over, the barber thought more about the people he didn’t save than the ones he did.

“There was a girl down on Clinton Street, not too far from me. Maybe I could’ve got a crew of people that was in the barbershop and helped,” Elston says. “She froze to death in her car.”

“They share food, they shovel driveways”

Nor did the region recover easily. As the storm moved out, tales of tragic deaths poured in. City officials faced tough criticism for being slow to close roads. Cleanup took months.

But along with the tragedies came tale after tale of courage and compassion. Buffalo would spend weeks celebrating its “blizzard heroes” with official awards and tickets to Bills games. Those heroes invariably shared the credit with the city itself.

“Buffalo is a city of good neighbors, great neighbors actually. We’re all just a big family,” says Withey, who broke into the school. “Everyone just sticks together, and we’re resilient. You can’t put us down.”

The near-death experience of Bills safety Damar Hamlin only added to the frenzy. Throughout the 2022 season, the team had been one of the NFL’s best. But just a week after the deadly blizzard, Hamlin almost died on the field when a hard hit stopped his heart. In a moment, fans around the region went from praying for victory to praying for a young man’s life.

“It drew everybody together,” Miller says. “Everybody pulling together, making sure the kids knew what was happening.”

The Bills would fall short of a Super Bowl once again, but Hamlin survived. While he recovered, donations poured in to support his favorite cause, a modest online toy drive that would eventually raise more than $9 million. Between the blizzard and Hamlin’s near-death experience, for a few weeks Buffalo became the center of the media universe. Elston says he talked to at least 100 reporters eager to capture a little bit of the Buffalo spirit.

“Worldwide attention. Front page of Yahoo, front page of Google, CNN, ABC, NPR,” says Elston. “It was kind of overwhelming.”

But if the attention was new, Elston’s efforts were not. He’d been giving back to his community long before the blizzard hit.

“I sponsor a shoe giveaway. I give free haircuts for kids who keep their grades at 90 or above,” he says. He does much of that work with Ferguson, a longtime community activist. Last Thanksgiving, Ferguson and Elston helped give away 250 turkeys to needy families.

“Craig is one of my great young men,” Ferguson says. “We do things to impact the community any way we can.”

Elston says the inspiration for those efforts began with Russell, his old basketball coach.

“I can never pay Coach Russ back,” says Elston. “He’s the sole reason I am what I am today, helping my neighbors. He was so influential. I had no idea what it took to function as a young man. He drove me to games. Bought me basketball sneakers. One time he drove my grandmother to see me play, the only time she ever saw me play. That night I played my worst game. But I didn’t care.”

When Russell heard that praise, his heart swelled.

“I’m about 5 foot 5, but right now I feel about 7 feet tall,” he says.

Russell taught math and coached basketball for 25 years at Riverside, a neighborhood public school whose alumni include former NBA All-Star Cliff Robinson. Russell recalls Elston as a hard-nosed, focused player, but he’s most proud to see the man that Elston has become.

“The things that are important aren’t records or championships,” Russell says. “My biggest pleasure is seeing the guys doing well with their families, being leaders.”

And it’s people like Elston who keep Russell in Buffalo. While the blizzard had the coach trapped in his home,he saw his own neighbors doing for each other what Elston did on Fillmore Avenue: shoveling snow, checking on the elderly, sharing a laugh and a kind word.

“Buffalo’s got a lot of really good qualities. Good enough that I’ve stayed here myself after I retired,” Russell says. “People help each other out. They share food, they shovel driveways, they give you a shoulder to cry on—that’s underrated.”

That’s a familiar story to Ferguson, a Buffalo native who spent the storm making sure his 91-year-old mother stayed warm. All around, neighbors were helping one another however they could, he says.

“It reminds me of my father. He only had a fourth-grade education, but he was always helping,” Ferguson says. “He was always building something for somebody, or blowing snow off the sidewalk so people could get to the corner store.”

Today, Elston and C&C Cutz are still recovering from the storm. Sheltering people for five days took its toll on his equipment and his wallet. Between the broken gear and his utility bills, Elston figures the effort cost him about $20,000, only some of which was covered by donations to a GoFundMe account.

“I spent everything I had. I’m still trying to recover,” he says. “I had to replace almost every chair.”

Buffalo, likewise, is still recovering—from the storm and violence alike. The blizzard and the Tops supermarket shooting took a particular toll on Buffalo’s Black residents. Half of those killed by the blizzard were Black, and all 10 of those killed at Tops were Black as well. Around the city, people are having hard conversations about striving to correct inequities.

But as officials wrangle with policy, Buffalo’s community members are stepping up in their own way. A survivors fund for victims of the Tops supermarket shooting raised more than $6 million. Damar Hamlin’s team has created a charitable fund called The Chasing M’s Foundation to help distribute the millions donated to Hamlin’s toy drive.

And down on Fillmore Avenue, the next time Buffalo needs help, Craig Elston will just think about the lessons he learned from Coach Russ.

“If I had to open up again, I would do it,” Elston says. “It was the right thing to do. I’m not a hero. I’m still just a barber. Just working hard and grinding, same as before.”