I Survived! Three Tales of Daring Escapes and Survivals

Updated: Oct. 05, 2023

These lucky survivors each escaped potentially deadly situations with their lives

“I survived my flooded apartment”

Christian Fleischmann, 33

I finally climbed into bed at 1:20 in the morning. It was July 15, 2021, and my friends had helped me celebrate my 31st birthday in the basement apartment of my sister’s home, where I lived.

Earlier in the day I had prepared for the unlikely event of a flood. We are about a third of a mile from the banks of the Ahr River in Sinzig, Germany. It had been raining buckets that week, and authorities had issued a flood warning, though not for where I was. Still, I’d placed sandbags on the floor outside my garden door and piled electronics and clothing on tables and the couch just in case water managed to seep through. Before my friends left, they laughed at me for doing that, but I thought, Why take a chance?

As I drifted off to sleep, I was awakened by the sound of rushing water, as if I were lying beside a waterfall instead of in my bedroom. When I swung my legs off the bed, I was shocked by the sensation of cold water lapping against my knees and rising fast.

It has to be from a burst pipe in the bathroom, I thought. Shivering and in darkness, I grabbed my cellphone and turned on the flashlight. When I stepped from the bedroom to the hallway, I saw it wasn’t a burst pipe at all. Instead, water was shooting through the gaps of the garden door that leads from my living room to a set of concrete stairs up to the backyard. The water must have breached the sandbags. All around me, my things began to float by: chairs, bookshelves, pieces of my drum set.

I admit it, I began to panic. The Ahr, usually such a quiet, slow-moving river, had violently burst its banks. And now I had to get out—fast!

Any effects of the celebratory drinks I’d had earlier were now gone; fear sobered me right up. I heard the garden door starting to crack and splinter under the pressure of the flood. The sound was like nothing else—screeching, hissing and crashing all at once. It was relentless. And the water was now up to my waist. In bare feet and with my boxer shorts plastered to my body, I started to wade to my only escape: the door that leads upstairs to the rest of the house. All around me things were breaking—the lamps were shattering, the cupboards were being torn apart.

Finally I made it to the door. I tried to pull it open, but the force of the water wouldn’t let me. I tried several times to pry it open even just a little bit, but the rushing water slammed it shut again.

I looked around for anything I could use to wedge the door open. There in the corner were a broom, a coat rack and a huge, heavy sword from a medieval fair. I grabbed them all and, once again, pried open the door, throwing the broom and coat rack between the door and the frame to keep the door from shutting, and using the sword to wedge it open some more.

I managed to make a gap of about a foot, just wide enough to squeeze through and make it into the hallway. In the pitch-black, I leaped onto the stairs leading up to the rest of the house and ran to the third floor, where my sister lived. I knocked on her door, calling for her, trying to see if she was OK, until I remembered that she wasn’t home that night.

That’s when I went downstairs to the main floor and ran outside. I stood there in the darkness, soaked and panting. What was once a lovely, cozy street was now a waterscape, with floating debris and trees instead of people and cars. The river had drowned the neighborhood—and if I had woken up just a few minutes later, I would have drowned along with it.

We’ve been assured that something like this happens only once every 100 years. I hope so. More than 180 people died, and parts of villages in the region were entirely washed away.

These days, I’m living at my parents’ place in the middle of town and sleeping in my dad’s office. I study psychology at a university and work with children in schools, teaching them martial arts. I can never go back to live in that apartment because I just keep thinking, What if it does happen again?

We didn’t have flood insurance because the house wasn’t considered to be located in a high-risk area, so we’re fixing it up on our own. My old apartment, once it’s dried out and repaired, will house my martial arts school.

Many of the houses around us were destroyed, including, tragically, a home for the handicapped. Not everyone got out.

I came close to drowning that day. But rather than dwell on that, I prefer to recall what my mother told me afterward: “Christian, don’t remember the day when you lost everything. Remember the day you survived.”

“I survived a parachute malfunction”

Jordan Hatmaker, 36

Nov. 14, 2021, was a perfect day for skydiving: sunny, with little wind. I was a novice solo jumper, having jumped only 14 times—not enough to be licensed. It scared me, for sure, but a little fear always makes you a better risk-taker, right? That’s what drew me to skydiving in the first place. I’ve always liked flirting with danger.

I left my home in Virginia Beach, Virginia, late in the morning and arrived at the hangar in Suffolk, Virginia, 40 minutes later. At around 1:30 p.m., I joined 15 other skydivers for our first jump of the day. As the plane ascended, I went through the safety protocols with my coach, a ritual you go through for every jump, no matter how much experience you have. This includes pointing from the plane door to the drop zone where you land 13,500 feet below, so you can direct your jump.

After the plane leveled off, we jumped, me first, then my coach, free-falling at about 125 miles an hour, descending about 1,000 feet every five seconds. It was exhilarating and terrifying all at once, with the world opening up before me, coming into focus in mere seconds, even though it felt as if it were happening in slow motion.

The wind eddies carried me for the free fall, and at about 4,000 feet I deployed my pilot chute—the small parachute used to extract the main one. After the main chute was released and inflated, I had about a minute to enjoy the peace and quiet as I floated gently toward the soft grassy meadow. I felt invincible.

We went up again not long after for a second jump. The mood on the plane was light—lots of joking, lots of laughing. My coach and I still made time to go through our prepping routine, then we jumped.

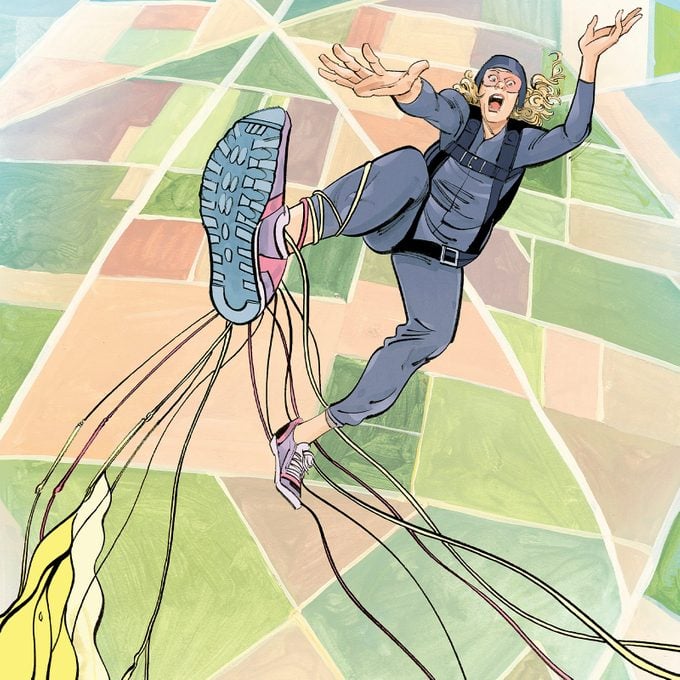

After 30 seconds in the air, at around 5,500 feet, we tracked away from each other because you need lots of empty space to safely deploy your parachute. I looked at my altimeter and realized I was lower than I’d thought. The ground was coming up too fast! I knew I had to pull the pilot chute at roughly 4,000 feet, as I’d done the last time, but I was caught off guard. As I cruised past that marker, I rushed to pull my chute without taking the time to stabilize my body position. When I pulled it, instead of releasing into the airstream to inflate, the pilot chute wrapped around my right leg.

The chute was pulling my right leg up as if I were a marionette, while the main parachute remained in its bag. Just get it off, I told myself calmly. I wasted about seven seconds trying to get untangled but was unsuccessful.

With the ground rapidly getting closer below me, I prepared to crash. I didn’t think it would be a catastrophic impact. Maybe you’ll break a leg, I thought.

I’ve always been an optimist.

Then, suddenly—and thankfully—the automatic reserve parachute (a backup that releases when the main one isn’t working) opened. I managed to gain some control, steering myself toward some grass, which I hoped would make for a softer landing.

I had just a few seconds to feel some relief before the main parachute inexplicably released from its bag. It inflated, and the two parachutes began pulling in opposite directions, causing me to accelerate hard and fast toward the ground, not far from the drop zone.

When my body smashed into the ground, I felt as if my muscles and bones were on fire. I tried to get up because that’s what you’re supposed to do if you don’t land on your feet. It shows everyone you’re OK. But I wasn’t OK. I couldn’t move anything below my waist. So I lay there, my face in the grass, my arms flung out to either side, and I screamed, “Please, somebody help!” In between calling for help, I prayed out loud. “Please, God, don’t let me be paralyzed.”

I lay with my face buried in the grass, fully conscious, for about five minutes before people from the skydiving club got there. They quickly surrounded me, eager to help, but there was nothing they could do. It was too risky to move me before the paramedics arrived. So they sat there listening to me swearing and yelling as the shock wore off and the pain really set in.

When the first two paramedics arrived with an ambulance half an hour later, they tried to move me onto a board for transport. It hurt so much, I screamed. Then I heard the helicopter.

The air ambulance crew came equipped with painkillers, which sent me to la-la land, and I was transported to the nearest trauma center.

In the end, my injuries were pretty severe: a shattered ankle, a broken shin and a spinal injury that caused a spinal fluid leak. No one could tell me if I would walk again. But I was determined, and in February 2022, just three months after the crash, I walked again for the first time. I began a heavy course of physical therapy that I’m still doing. And, after being unable to even liftmy legs because of the accident, last November I climbed to the Mount Everest base camp.

Oh, and I plan to skydive again—only I haven’t told my parents yet.

“I survived a ‘snownado’”

Shannon St. Onge, 38

The snowstorm was supposed to hit the evening of Monday, Jan. 31, 2022. I was working from home, but I had to leave that afternoon and go to my office at First Nations University in Regina, Saskatchewan, so I could sign an emergency financial aid check for a student. As director of finance, I wanted to get it to him as soon as possible, snowstorm or not. Besides, I wasn’t worried. I figured I had more than enough time to make it to the office and get back home.

The route to the university takes about 30 minutes along the Trans-Canada Highway. When I got there, my colleague came to my office to co-sign the check, then he left for the day. As I was packing up, I noticed he had left his laptop bag in my office.

“Shoot,” he said when I called him. “I’m already home.”

“I can bring it to you,” I assured him. It was just past 4:30 p.m. The snow wasn’t supposed to start until later, but just to be safe, I decided to take the country roads to his home instead of the highway, which could fast become a skating rink. On the way to his place, I picked up a new cellphone charger, filled up my SUV with gas and picked up two stuffed-crust pizzas because I’d promised my 15-year-old daughter and 10-year-old son I’d bring some home for dinner.

It took me about 15 minutes to get to my colleague’s house, where I dropped off the laptop case and got right back on the road. Then the snow started—and it was coming down fast. Within minutes I was in a whiteout. The storm was a “snownado,” or what the TV meteorologists call a Saskatchewan screamer, because it comes in fast and so windy that it screams.

The road soon switched from paved to gravel, forcing me to slow down. The windows were fogging up and getting covered with snow, so I rolled down my driver’s side window, thinking I could better follow the edge of the road and keep to a straight line. But really, I didn’t have a clue where I was or even which side of the road I was on. At one point, I don’t know exactly when, I stopped because I was afraid of driving into a farmer’s field, a ditch or worse. I kept the car running to stay warm and called 911. The dispatcher told me to sit tight and wait things out for the night—nobody was coming to get me until morning, at the earliest.

Those seconds after the call were agony. Getting out to walk in a whiteout with zero visibility, high winds and a temperature that was hovering around 14 degrees—when I didn’t even know where I was—wasn’t an option. But I worried other drivers wouldn’t see me and would barrel into the car from the front or behind. Or the tailpipe would get clogged with snow and I’d die from carbon monoxide poisoning. Or the storm would continue for longer than predicted and I’d be found too late.

Breathe, I told myself. Panicking won’t help.

My kids! It was the first time they would ever be spending a night without me at home. I called and told them what was happening, forcing myself to sound calm. I didn’t tell them I was terrified. That I, a problem solver all my life, couldn’t figure out what to do.

It was now about 6 p.m. and dark. What would my black Ford Edge SUV look like in a whiteout at night? Would it appear as a shadow? Or worse, would it be invisible?

Suddenly a truck drove by, barely missing me. It was close. But surprise soon turned to thoughts of salvation. I put the car in drive and followed the truck, desperate, with no idea where we were heading. When it suddenly turned, I didn’t know what to do.

“I’m going to the beach,” the driver shouted through his open window, his words almost lost in the wind.

I knew the beach wasn’t in the direction of my home, but I had no idea where I was. So I stopped the car and texted my colleague whose laptop bag I had just returned. I joked about my good deed ending in disaster. But he had an idea. “Pin your location on Google Maps and send it to me,” he said.

I did, and a few minutes later he texted me back a screenshot of the satellite view of where I was. We figured out that I was on a road called Bouvier Lane, in between two farms. It was now 6:30 p.m. I posted this new information to my Facebook community group, pleading for anyone who knew who lived on the farms to help me get rescued.

After that, all I could do was sit in the car and try to stay warm. I was so glad that I’d just filled it up. I’d done all I could, and no matter what happened, I had to be at peace with that. But even if someone did figure out where I was, would help be able to come through the swirling snow and shrieking wind?

Soon enough, though, people started chiming in on my post. They knew the family who lived there! I got a message from someone who was going to put me in touch with them.

At 8 p.m., my cellphone rang. It was the son of the farmer who owned the land beside the road I was stranded on. He told me that his dad was coming to get me.

Then, about 45 minutes later, I saw a tall figure in a yellow rain slicker striding toward me in the dark, carrying a flashlight. I’d never been more relieved to see someone in my life. It was André Bouvier, who’d walked about 550 yards through the blizzard to come get me, fighting the wind and snow each step of the way, shielding his eyes from the stinging snow with a mittened hand.

“Can you drive?” I asked, shakily. “My nerves are shot.” He thrust his face closer to mine. It was then that I noticed the silver hair and wrinkled skin of an elderly man.

“No,” he replied, his voice steady. “I want you to follow me in your car. You’ll be OK.”

He turned around and started to trudge through the snow, sure of the direction. I drove slowly behind him, clutching the wheel, feeling my heart begin to beat more slowly. When we reached the house, I got out of the car and burst into tears, all my fears turning into relief and gratitude.

As his wife, Maryann Bouvier, treated me to hot drinks and applesauce, André, who was 80 years old, said he’d noticed two other cars stranded, too, and he went back out into the storm to get them: a father and his two kids, and a couple with their daughter.

We all spent the night telling stories, the kids ate the pizza I’d bought, and we slept scattered around the house, on sofas and reclining chairs. By 5:30 the next morning, André had cleared the snow from his driveway enough that we could all get out and drive home, which, in my case, was only five minutes away. The storm had turned me around so much, I didn’t realize how close I was. Even so, I couldn’t have gone any farther without risking my life.

The experience has been a game changer for me. I now approach challenges with a sense of calm I’d not known before.

But best of all, it brought André into my life. We’re still in touch, and I know we’ll be friends forever.