Mitch Albom on What It Means to Be a Real Father to a Special Orphan

Updated: Nov. 08, 2022

What is a real father? An orphan in Haiti teaches bestselling author Mitch Albom a wonderful new definition.

Shortly after a major earthquake decimated Haiti in 2010, Mitch Albom and his wife, Janine Albom, decided to take over operations at a struggling orphanage in Port-au-Prince. The children there became like family to the Alboms, especially one little girl named Chika. But at the age of five, Chika became ill. Her diagnosis: a rare brain tumor that no doctor in Haiti could treat. Though the Alboms never formally adopted Chika, they brought her home with them to Detroit to make sure she got the best medical care—just as any parent would.

Chika’s father is alive.

We were always told he was dead. Now we are told differently. This is not uncommon in the Haitian orphan world. Adults who bring us children will sometimes say the parents are deceased to increase the kids’ odds of acceptance.

Driving to the father’s house, we meander through traffic out to a rural agricultural landscape. We park on a dirt road. There’s a small square of land with a large breadfruit tree.

This is where Chika was born. And stepping out in front of me is her father.

He is small and compact, maybe five foot six, with a wide mustache, a full head of hair, and deep bags under his eyes, which are bloodshot red. They rarely meet mine. I ask about his upbringing. I ask about Chika’s infancy. He answers every inquiry with very few words.

He says he was there when Chika was born but was not at home when the earthquake happened. He confirms that after Chika’s mother died, all four of his kids went to live with other people. He doesn’t say why.

I ask whether he knew Chika was brought to our orphanage when she was three.

“Yes, I knew.”

And it was all right with you?

“It was all right with me.”

I don’t ask why he didn’t want Chika back, even though part of me screams for an answer. I remind myself I can never know the circumstances of his life or its hardships. I remind myself he lost his partner, the mother of his children.

I explain the reason I have come. Chika’s medical condition. The brain tumor. He nods now and then, although I’m not sure he understands.

“Whatever you think is best,” he says, “you do.”

I explain that her life could be in the balance. I say I have a hard question. If Chika should not survive, is it important to him that she be buried here in Haiti? I hate even saying the words, it makes me physically shiver, but it feels like something I must ask him.

“It doesn’t matter,” he says. “Whatever you think.”

I struggle to keep the conversation going. I invite him to the mission. I want him to see his daughter—and her to see him—perhaps because, deep down, I don’t know if they will get another chance. We drive back together, and as we approach the gates, there is part of me that feels suddenly extraneous, as if I’ve been nudged to the side of the picture. For all Janine and I have done with Chika, this man has a certain claim that we never will.

When we arrive, Chika is playing in the gazebo. She is sweating heavily.

“Chika,” I ask, “do you know who this is?” She looks up.

“It’s your daddy. Can you give him a hug?” (I say this in English so as not to embarrass him.)

She does. I leave them alone.

He sits on a bench, wearing a long-sleeved shirt despite the heat, and she sits next to him. From time to time I look over, but I never see them speaking. The sun bakes down.

After two hours, the father walks over, shakes my hand, and leaves.

Yours, not yours. We wrestled with this question many times, Chika. Remember what you once asked? How did you find me? I promised myself you would never feel lost again.

But seeing your father that day touched a nerve. True, we had to track him down. And he left the mission almost as quickly as he entered it. But what if he hadn’t? What if he had said, “I’ll take it from here”? Would I have been able, given your medical situation, to turn you over? To trust a man who had been so absent from your life to suddenly try and save it? Would I have been doing right by you? What about doing right by him?

Is it true, as Pope John XXIII once said, that it’s easier for a father to have children than for children to have a real father? Who steps aside? It’s a debate that foster parents deal with regularly and why adoption agencies have strict rules on parental rights.

But we were neither of these. We were—we are—a place of love and shelter for Haitian children with few options. And when your health was threatened and we brought you to Michigan and you were lying on that hospital gurney with tubes and monitors and a white bandage around your little head, who had claim to you was the furthest thing from our minds.

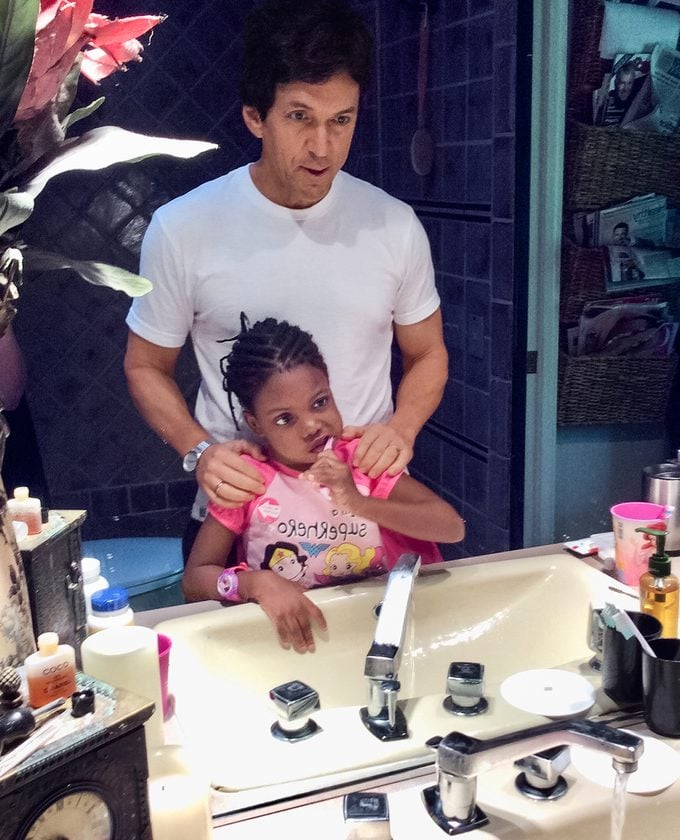

Occasionally, by the way, even friends would use the yours word. “It’s great what you’re doing for a child that’s not yours.” It puzzled me to think there would be any difference in our efforts if somehow you had our DNA. I remember the time we stood by a mirror, studying our reflections, and you held your arm up next to mine. I thought you were comparing our skin color. Instead, you pointed to a mole near my wrist and said, “Mister Mitch, why do you have that bump?” That’s all you were interested in.

Yours, not yours. The paperwork at the orphanage is signed by me. It obligates us to nurture, feed, educate, and protect the children—all things mothers and fathers are supposed to do. But in the end, it is a document of responsibility, not parenthood. I am, for all our kids, just Mr. Mitch, their “legal guardian,” the words I used at the first hospital you and I went to, Chika. It feels sometimes like a diminished title. Still, when I look around, it is me, or Miss Janine, or our compassionate staff at the mission, kissing the children goodnight, waking them every morning, tying their shoes, cutting their sandwiches, reading them books, racing them to the doctor if something happens.

We did not bring any of these little souls into the world. That truth can never be overstated. But I wonder, Chika, whether anyone has blind claim over a child, save for God. I have witnessed the purest connection between an adoptive mother and her children, and I have witnessed helpless infants shunned by those who birthed them. The opposite also happens. After a while, you make peace with the truth: Love determines our bonds. It always comes down to that.

The day your father returned home, you ran a high fever, and you vomited again. And that night, while he slept in his cinder block house, you cried yourself to sleep at the mission. The next day, you seemed so weak that when the time came to leave, you didn’t even say goodbye to the kids. You just took my hand and led me to the car.

At the airport, you complained about walking, so I carried you through the lines, one arm tucked beneath you, one arm wheeling my roller bag. When we boarded the plane, I put a pillow on the armrest.

“Go to sleep, sweetheart,” I said softly.

You laid your head down and after a few seconds mumbled, “Mister Mitch?”

“Yes, Chika?”

“What will you do while I sleep?”

“I’ll read,” I said. “And think about how much I love you.”

You nodded, your eyes glazed.

“That’s what I’ll do too.”

At that moment, I didn’t care who belonged to whom. I was yours, even if you were not mine. And as I stroked your forehead, which was hot to the touch, I knew I always would be.

Excerpted from the book Finding Chika by Mitch Albom.