The Racist History of Mount Rushmore

Updated: May 07, 2021

The history of Mount Rushmore is racist in its origins and remains a potent symbol of the nation's betrayal of indigenous people.

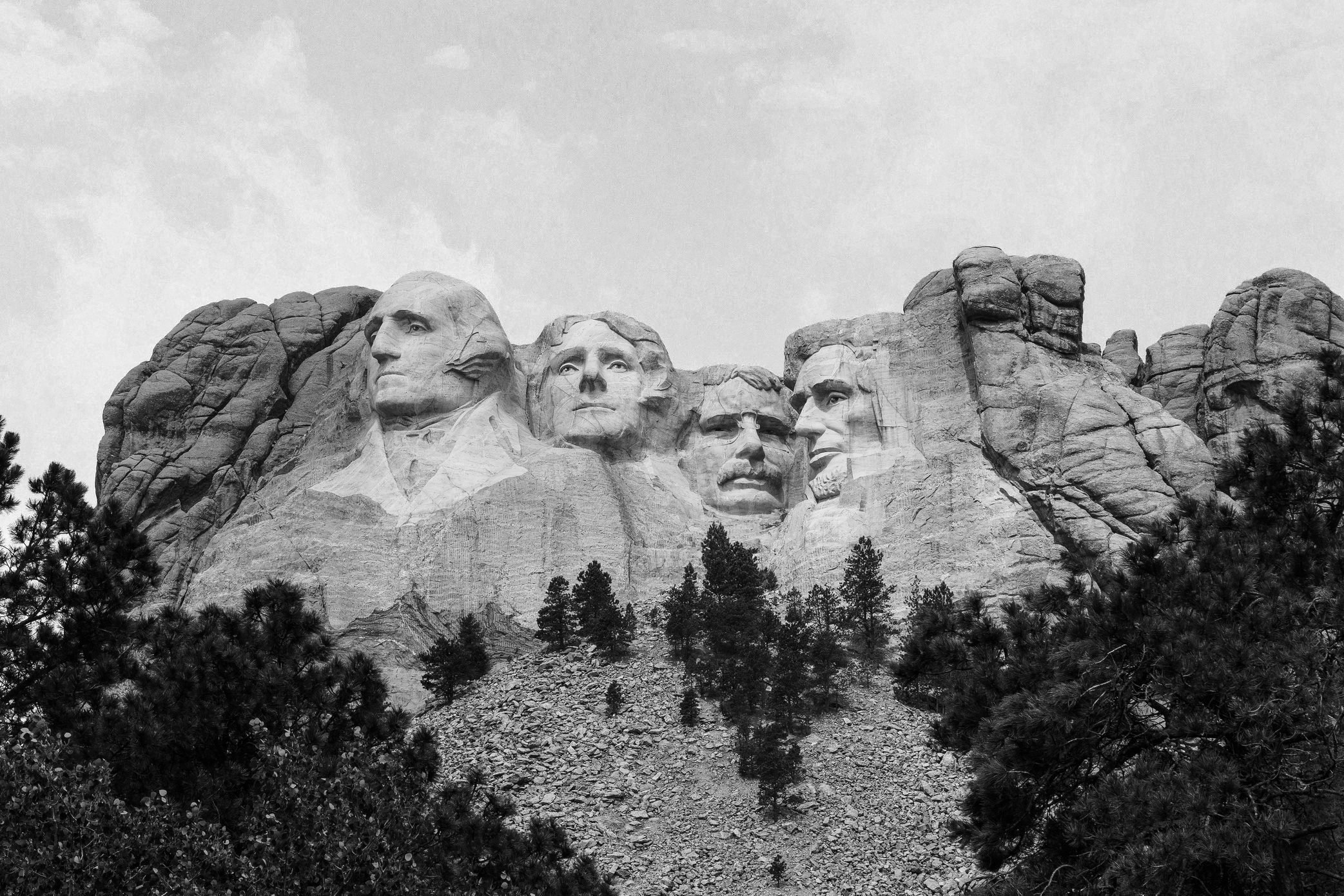

Each year, 2 million tourists visit Mount Rushmore, the mountain sculpture of four U.S. presidents. Located near Keystone in the Black Hills of South Dakota, this “shrine to democracy” has largely been seen as a symbol of patriotism and American greatness.

While the 60-foot visages of George Washington, Thomas Jefferson, Abraham Lincoln, and Theodore Roosevelt and a secret room that houses copies of the Declaration of Independence and Constitution, may seem like the perfect place to pay homage to the nation’s independence, for many Native Americans and a growing number of others concerned about social justice, this towering structure is a symbol of bigotry and oppression. Its creator, Gutzon Borglum, intended the monument to be a celebration of the nation’s manifest destiny, the doctrine that says the taking of any land needed for U.S. expansion was not only right but inevitable.

Mount Rushmore desecrates sacred land

Mount Rushmore was named for Charles E. Rushmore, a White New York City lawyer who visited the area in 1884. About a decade earlier, however, Lakota medicine man Nicolas Black Elk named it the Six Grandfathers after a vision of the ancestral spirits who appeared to him representing six sacred direction—west, east, north, south, above, and below. These directions were said to represent kindness and love, full of years and wisdom, like human grandfathers. Six Grandfathers was sacred to the Lakota Sioux who see the carvings as a desecration. How much do you know about these important Native American traditions and beliefs?

The U.S. violated a treaty with the indigenous people

The Black Hills, the land on which Mount Rushmore sits, was designated “unfit for civilization,” and “Permanent Indian Country” in the 1868 Fort Laramie Treaty. The United States entered into the treaty with the Dakota, Lakota, and Nakota, collectively known as the Sioux, and Arapaho. The treaty designated the Black Hills as “unceded Indian Territory” in perpetuity. But when gold was found in the Black Hills several years later, the United States broke the treaty and redrew the boundaries. The Sioux were confined to the reservation. By 1875, some 800 miners and fortune-seekers had flooded into the Hills to pan for gold on land that had been reserved by the treaty exclusively for the Native Americans. Lakota and Cheyenne warriors attacked the prospectors; this action resulted in the U.S. passing a decree confining all Lakotas, Cheyennes, and Arapahos to the reservation under threat of military action.

The Supreme Court ruled the land was stolen

Breaking the Fort Laramie treaty has been at the center of a legal dispute for more than 120 years. In 1980, the Supreme Court ruled in United States v. Sioux Nation of Indians that the land was taken illegally. “A more ripe and rank case of dishonorable dealing will never, in all probability, be found in our history,” the majority opinion stated. The Supreme Court also determined that the U.S. owed the Sioux Nation the 1877 price for the land, along with 100 years of interest, and awarded more than $100 million in reparations. The Sioux rejected the cash settlement, stating that the land was never for sale. The tribe still seeks return of the land today.

What Mount Rushmore has in common with Stone Mountain and other racist monuments

Beyond the land itself, the sculptor of Mount Rushmore and Stone Mountain in Georgia owe their beginnings to the same racist sculptor, Borglum, a man who expressed his solidarity with and support for white supremacy. The United Daughters of the Confederacy (UDOC) are responsible for the vast majority of the confederate statues and monuments erected during the Jim Crow era. UDOC president Helen Plane believed the KKK had “saved us from Negro domination and carpetbag rule.” She asked Bolgrum to honor that belief by carving a “shrine to the South” on Stone Mountain. Borglum sketched a 90-foot design that depicted Confederate leaders Robert E. Lee, Jefferson Davis, and Stonewall Jackson on horseback.

Beyond the land itself, the sculptor of Mount Rushmore and Stone Mountain in Georgia owe their beginnings to the same racist sculptor, Borglum, a man who expressed his solidarity with and support for white supremacy. The United Daughters of the Confederacy (UDOC) are responsible for the vast majority of the confederate statues and monuments erected during the Jim Crow era. UDOC president Helen Plane believed the KKK had “saved us from Negro domination and carpetbag rule.” She asked Bolgrum to honor that belief by carving a “shrine to the South” on Stone Mountain. Borglum sketched a 90-foot design that depicted Confederate leaders Robert E. Lee, Jefferson Davis, and Stonewall Jackson on horseback.

Although Borglum did not complete the Stone Mountain sculpture, his work captured the attention of South Dakota’s state historian who asked Borglum to create a tourist attraction that would attract visitors to this remote location. It has been wildly successful, despite being known as one of the most controversial statues and monuments around the world.

Sources:

- Vice: “Mount Rushmore’s Extremely Racist History”

- Smithsonian Magazine: “The Sordid History of Mount Rushmore”

- AAA Native Arts: “Symbolism of Black Elk’s Vision”