Snake Island, Brazil

Brazil’s Ilha da Queimada Grande—dubbed Snake Island—is home to a dense population of one of the world’s deadliest snakes. The golden lancehead viper’s venom is so poisonous that it melts human flesh around the bite, and some claim there’s one snake per square meter in certain areas. For safety reasons, the Brazilian government doesn’t allow visitors, and a doctor is required on the team of any research visits.

U.N. buffer zone, Cyprus

Turkish troops invaded Cyprus in 1974, sparking a civil war between the Greek and Turkish inhabitants. When the fighting ended in a ceasefire, the United Nations took control of a no-man’s land “buffer zone” in the country’s capital, Nicosia. There, walls separate the Turkish community in the North (which Turkey, but no other countries, recognizes as a separate state) from the Greek community in the South. Behind the walls are abandoned homes and businesses.

Tomb of the Qin Shi Huang, China

Farmers discovered the tomb of China’s first emperor, Qin Shi Huang, in 1974, and archaeologists have since found about 2,000 clay soldiers and expect there are another 8,000 still uncovered. Despite the excavation, the Chinese government has forbidden archaeologists from touching the central tomb with Qin Shi Huang’s body, which has been closed since 210 B.C.E. The decision is partly to respect the dead, but also from fear that current technology isn’t up to snuff for excavating without damaging the ancient artifacts.

Chernobyl, Ukraine

On April 26, 1986, an explosion near Chernobyl, Ukraine, (which was then in the Soviet Union) became the worst nuclear accident in history. Although the death counts caused by radiation are impossible to pin down, experts estimate between 9,000 and one million people will die of cancer from radiation. More than 30 years since the disaster, cleanup projects are still undergoing, and the power plant’s director guesses the area won’t be inhabitable for at least 20,000 years.

Area 51, Nevada

The U.S. government wouldn’t admit Area 51 existed until 1992 documents released in 2013 mentioned the Nevada military base. Officials still haven’t revealed what type of research goes on, though conspiracy theorists claim alien activity is studied there. You can get a birds-eye view of the spot on Google Maps, but the sprawling desert makes it hard for anyone to sneak in, and security is tight. Even visitors with security clearances reach Area 51 on private planes that keep the windows drawn until landing.

North Sentinel Island, India

In the Bay of Bengal sit the Andaman and Nicobar Islands, most of which are Indian territories. The Sentinelese tribe of North Sentinel Island is thought to have been there for 60,000 years, and it’s one of the last communities in the world to remain totally isolated from outside societies. In 2006, the boat of two fishermen drifted to the shallows of North Sentinel Island, where the Sentinelese killed the pair. Since then, there have been other reports of the tribe shooting arrows at passing helicopters. Because the Sentinelese haven’t been in contact with the diseases others have built resistance to, contact with outsiders could prove deadly to the tribe, so the Indian government has agreed not to attempt any contact. Don’t miss these other 25 weird international laws you’d never believe are real.

Vatican Secret Archives, Vatican City

Housed in a heavily protected area of the Vatican are 53 miles of shelves containing documents relating to the Catholic Church, dating as far back as the eighth century. Some artifacts include a letter from Mary Queen of Scots begging Pop Sixtus V to save her from beheading and documents of Martin Luther’s excommunication. The archive opened to researchers in 1881, but it isn’t easy to get a pass inside. Researchers who apply for access can only have access for up to three months, and no more than 60 scholars are allowed in at once.

Fort Knox, Kentucky

The Fort Knox vaults, home to most U.S. gold reserves, have been deemed the most heavily guarded place on the planet. No single person can make it into the vault; several combinations need to be entered to gain access, and various staff members know just one. Even they wouldn’t be able to get in without the help of their colleagues. Here’s more about Fort Knox’s insane security measures.

Svalbard Seed Vault

Plunging more than 320 feet into a mountain between Norway and the North Pole, the Svalbard Seed Vault holds a massive collection of seeds in a vault designed to withstand manmade and natural disasters. If a major catastrophe happened, the 890,000 preserved seed samples from almost every country in the world would ensure diverse food options. The vault opens its doors just a few times a year, and a limited number of depositors are allowed inside to deliver the seeds to its shelves. Still, climate change might test how effective the Svalbard Seed Vault is. In May 2017, melted permafrost made it inside, though none of the water—which froze inside—reached the vault with the leaves.

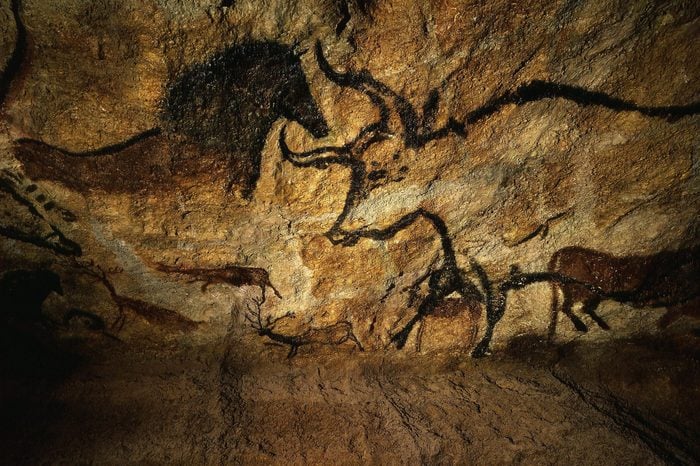

Lascaux cave, France

The prehistoric paintings in the Lascaux cave were found in 1940, and it became a tourist site after World War II. The carbon monoxide from visitors’ breath started to damage the cave paintings, which are now named a UNESCO World Heritage Site, and the cave closed to the public in 1963. Replicas opened for business after it closed, but only preservationists and researchers are allowed in the original.