Weird but true!

Your Election Day routine in 2020 will probably be fairly straightforward: You’ll wake up, go to the polls, cast your ballot, and go to work. In the evening, you’ll likely gather around the TV to watch the results. But if you lived in colonial times, your Election Day routine would look a lot different—and some of the activities you’d probably participate in might shock modern-day voters. For example, did you know that early American elections were typically boozy affairs during which candidates provided voters with alcohol? Or that in some colonies, votes were cast out loud, instead of via secret ballots? We’ve rounded up some of the most interesting tidbits about America’s earliest elections. From who was allowed to vote to how many gallons of rum were typically consumed, these crazy facts show just how much the big day has changed since the birth of our nation. For more U.S. trivia, don’t miss these 50 facts about America that most Americans don’t know.

Voters traveled from far and wide to cast their ballots

Nowadays, most of us live at least somewhat close to our polling sites. But in colonial America, that wasn’t the case—and because of that, the event was treated as a jubilant reunion and celebratory event. “Since colonial settlements were usually some distance apart, it was a time for friends and neighbors to meet, catch up on news and generally have a good time,” writes Kate Kelly in her book Election Day: An American Holiday, An American History. In some places, constituents who lived on the outskirts of a settlement would meet up with others traveling from the same direction to form a parade into town. Elections for representatives to the colonial assembly drew the biggest crowds and were the most important. Next, learn the answers to these 19 political questions you’ve been too embarrassed to ask.

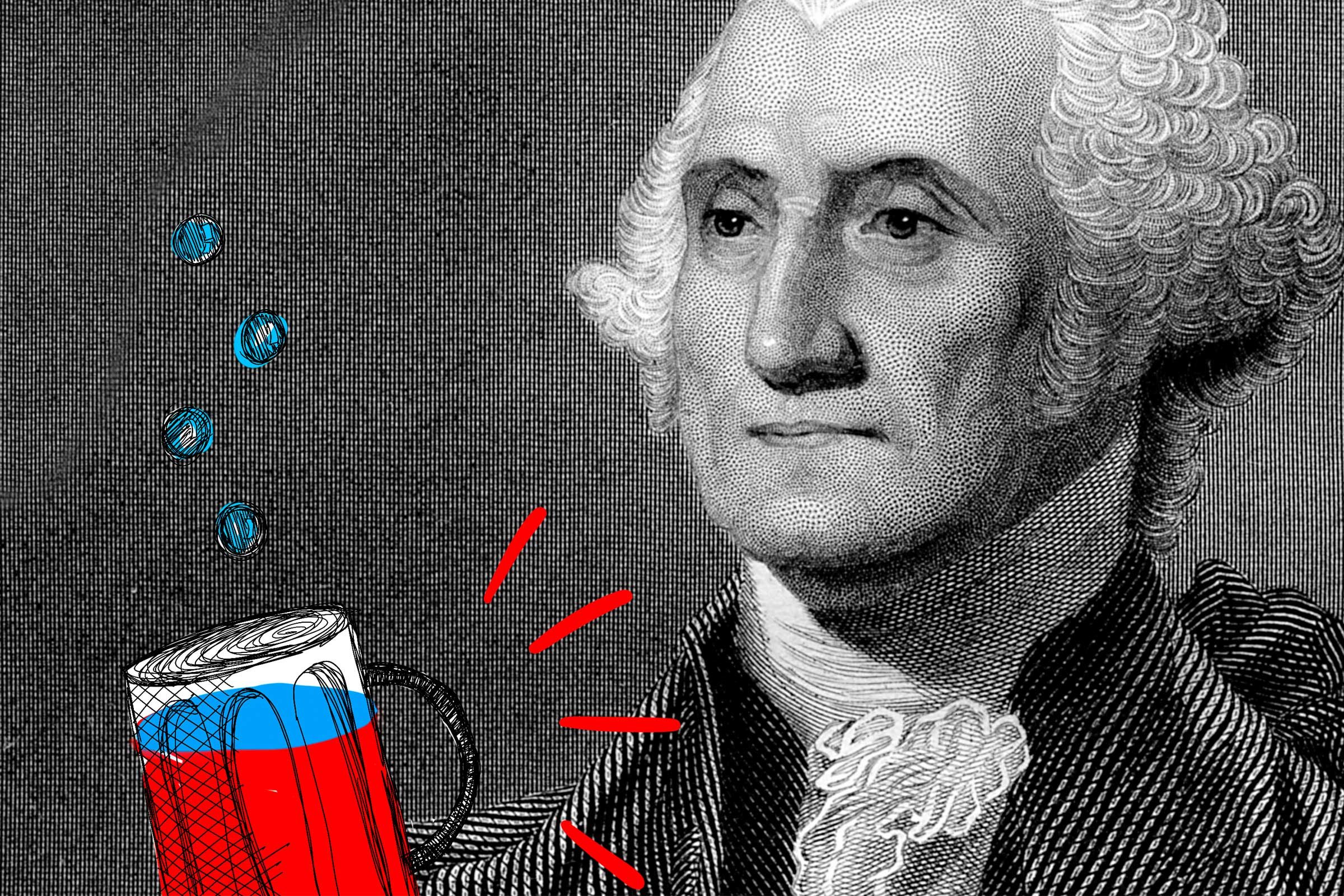

Candidates—including George Washington—plied voters with booze

You might grab a drink with friends on Election Day, but your day probably doesn’t include as much booze as it often did back in the day. And even if it does, it definitely doesn’t include booze provided by the candidates. In colonial times, however, it might have. Although it was technically illegal to bribe voters, many politicians brought food and drinks to the polls to offer their constituents; even a young George Washington participated. According to History.com, when Washington ran for the Virginia House of Burgesses in 1758, he doled out enough alcohol to stock a small bar: 47 gallons of beer, 35 gallons of wine, 2 gallons of cider, 3.5 pints of brandy, and 70 gallons of rum punch. Unsurprisingly, he won by a landslide with 310 votes. Get ready for this year’s election by reading these 14 inspiring quotes about democracy.

Votes were cast aloud, instead of via secret ballots

In colonial times, there weren’t uniform voting methods, and different colonies conducted their elections in different ways. For example, in some places, votes were done via a show of hands, while in others, voters would shuffle to one side of the town green or another to show how they felt about an issue. But according to Kelly, casting oral votes was the most common voting method, and during the 18th century, at least half of the colonies used it at one time or another. To cast an oral vote, a person would announce their preferred candidate to the sheriff, and a clerk would write down their choice. The candidate for whom the voter had chosen would stand, bow, and thank the voter. Do you know the truth regarding these 18 history lessons your teachers lied to you about?

Not everyone could vote

Early elections weren’t as democratic as they are today, and in colonial America, only a small fraction of people who lived in a colony could vote in its elections. African Americans, Native Americans, women, and White men who did not own land were all excluded. Historians believe that in Pennsylvania in the early 1700s, when voters were required to own 50 acres of land or have property valued at $50 or more, only 8 percent of the rural population qualified to vote—and only 2 percent of Philadelphians did. According to the Constitutional Rights Foundation, other estimates suggest the colonial electorate generally consisted of around 10 to 20 percent of the total population. We may take it for granted today, but the fact that all U.S. citizens have the right to vote is a big deal.

Women could vote in New Jersey for three decades after the American Revolution

Yep, you read that right. More than a century before the 19th Amendment was ratified in 1920, women were legally allowed to vote in the state of New Jersey; a 1797 statute explicitly referred to voters as “he or she.” While historians are unsure if this ability to cast a ballot was a legal loophole or a genuine effort toward gender equality, they do have evidence that New Jersey women showed up at the polls in significant numbers. Unfortunately, the right was revoked in 1807 after reports of alleged voter fraud and other mischief, including stories of men who would dress as women in order to vote multiple times. Here are another 20 states where women could vote before 1920.

Voter fraud was a major concern

Today, voter fraud is relatively rare, but in colonial times, it ran rampant. And with such a small electorate, just a few cases could sway an election. According to the Constitutional Rights Foundation, “Sometimes large landowners would grant temporary freeholds to landless men who then handed the deeds back after voting. Individuals were paid to vote a certain way or paid not to vote at all. Corrupt voting officials would allow unqualified persons to vote while denying legitimate voters the right to cast their ballots. Intimidation and threats, even violence, were used to persuade people how to vote. Ballots were faked, purposely miscounted, ‘lost,’ and destroyed.” To make sure your vote is properly counted, don’t miss these 8 red flags voter suppression is happening in your area.

The winning candidate bought everyone drinks at raucous after-parties

Like any good celebration, the Election Day festivities didn’t end once the votes were cast. It turns out, there were also rowdy after-parties. According to historian Nicholas Varga, in New York in 1768, “it was customary for everyone present to adjourn [from the election green] to the nearest tavern, where the winning candidate was expected to treat all the electors (regardless of how they had voted) to more drink and food.” That’s one way to get everybody on your side quickly.

African Americans had Election Day festivals

African American men didn’t gain the right to vote until 1870. But before that, they elected leaders of their own communities on the same day that White communities did, and in a similarly celebratory manner. In New England, this festival was called Negro Election Day. According to the Encyclopedia of African American History, “The festivities associated with Negro Election Day included dancing, gambling, and the consumption of special foods and drinks, such as gingerbread and herbal beer.” The celebrations allowed enslaved people to keep their African heritage alive and recognize their community leaders. In some cases, the elected officials chosen on Negro Election Day acted as a liaison between the Black and White communities. Learn about these 35 Black Americans who were left out of the history books.

Election Day typically began with a special sermon

Religion was important to the American colonists, and because of that, Election Day began with a sermon. In New England, this tradition lasted for hundreds of years. Connecticut’s Election Day sermons took place from 1674 to 1830, while Massachusetts’ sermons were held for 250 years from 1634 to 1884. Each year, a different minister was chosen to deliver the sermon, and the responsibility was considered a great honor. “Kept to an hour or under because of all the other business to be covered during the day, the sermons were usually quite theatrical,” writes Kelly. “Always thankful for the good of the past, the clergyman also found time to catalog what was wrong with New England, plead with the audience to do better, and take a look at what might lie ahead. Voters were always reminded to elect good men and then leave them alone to govern.” Can you guess which state produced the most presidents?

Townspeople baked traditional “election cakes”

Just like many other major holidays, Election Day in colonial America had specific foods associated with it. The most prominent example is “election cake,” a sweet treat that can be traced back to elections in Hartford, Connecticut, as early as 1660. According to the New York Public Library, historians believe election cakes were adapted from yeast bread recipes that were popular in England at the time. So, how do you make an election cake? The first printed recipe ran in Amelia Simmons’ 1796 edition of American Cookery. It called for “30 quarts flour, 10 pound butter, 14 pound sugar, 12 pound raisins, 3 dozen eggs.” Given the large quantities of ingredients required for the recipe, it’s clear these election cakes were made to feed a crowd. Colonial women worked for days in order to make enough food to serve guests who came from out of town for the election. These 15 countries gave women the right to vote before the United States did.

Candidates distributed odd souvenirs—like soap babies

So, uh, what’s a soap baby? You might wish you never asked. Before bumper stickers, coffee mugs, and T-shirts became the campaign merchandise of choice, candidates resorted to more, er, creative options. For example, consider soap babies, which were distributed by presidential candidate William McKinley in 1896. The souvenirs were exactly what they sound like: soap bars shaped like babies. They came in boxes that read: “My Papa will vote for McKinley.” The soaps were likely retired after voters noted they bore a striking resemblance to a baby in a coffin. Also odd? These 11 strange things presidents have banned from the White House.

Candidates didn’t campaign like they do now

In modern elections, campaigns and debates can start years before any ballots are cast. But in earlier elections, that wasn’t the case. In fact, making speeches and schmoozing with voters was downright frowned upon, even when it came to the highest office in the land: the presidency. According to the Roosevelt House at Hunter College, “Presidential candidates initially did not travel to campaign: They were called to be the nominees but it was considered inappropriate to ask voters directly to vote for them.” Instead, it was up to supporters to organize events and even speak on their candidate’s behalf. Parades and rallies were all held by supporters, and on the day of the election, these folks would even rally potential voters at nearby taverns.

Election Day was one of the biggest holidays of the year

Today, some companies might give workers off for Election Day, but it isn’t the major holiday it used to be. In early America, colonists believed Election Day was one of the most important annual holidays, and they celebrated it as such. “Shops and schools were closed, and town inhabitants, dressed in their finery, gathered in the marketplace,” writes Kelly. “Especially in port towns, the residents were usually joined by visitors who wanted to observe the celebration. In communities where nearby Indian tribes were friendly, sometimes an Indian chief, dressed in ceremonial garb, came to town to witness the holiday.”

Some experts say modern American elections could benefit from reintroducing some of this fanfare. “Declaring Election Day a federal holiday and rekindling the celebratory spirit that marked the day in previous centuries would be an important step toward promoting democratic participation,” wrote Holly Jackson, author of American Radicals: How Nineteenth-Century Protest Shaped the Nation, for the Washington Post in 2018. “But we must also depart from our history to create an inclusive Election Day in which all Americans can take part.”