I Was Personally Blamed for the Terrorist Attacks on 9/11—Here’s What Happened

Updated: Apr. 01, 2022

You've heard a whole host of stories about the terrorist attacks on 9/11, but you probably haven't heard this one.

September 11, 2001, is a day I’ll never forget, like anyone else who lived through it. It was a devastating day on which so many innocent lives were lost, and it was also the day my life was hijacked by a national narrative I couldn’t control. I was the CEO of the Massachusetts Port Authority at the time, and in the aftermath, I was personally blamed for the attacks—a burden that proved to be almost too much to bear. I lost my job, my colleagues, and the respect of my nation. I’ve decided to tell my story now because it’s one of redemption against all odds, and if redemption is possible for me, then it is really is possible for anyone.

A day like any other

On the morning of September 11th, I was a working mom with a two-year-old son, and I was five weeks pregnant with my daughter. I was 36 at the time and had been appointed the CEO of the Massachusetts Port Authority, which also meant that I was the head of Logan International Airport for two years prior. The position was a politically appointed one, and I had already served as Chief of Staff to two Massachusetts governors. It was going well, up until that day. We had been working on getting support to build a new runway, and we were making good progress.

The call that changed everything

That Tuesday morning, I was actually on my way to Logan to catch a flight to D.C. I was scheduled to meet with the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA). I was listening to the radio when I heard the report of the plane hitting the first tower. I thought it must have been an accident like a lot of people did, and then, I listened live as they reported the second plane hitting the other tower. Then I knew it was terrorism. A staff member called me and said the six words that haunt me to this day: “Two planes are off the radar.” Those two planes had been hijacked and were the ones that had hit the towers—and they were from Logan. I wanted to weep as I heard the reports coming out of New York, but I knew I couldn’t freeze in the face of the horror that was happening. I could not scream. I could not cry. I had to do my job, and I had to lead Logan through this.

The center of a firestorm

No one knew at the time how the hijackers could have gotten through security. We know now that they carried small knives or box cutters through that went undiscovered. (Editor’s note: Blades four inches or less were permitted on flights at the time, so the ones the hijackers used would not have been confiscated.) This sparked a lot of anger, most of it directed at me. Suddenly, I found myself in the middle of a media firestorm. Story after story, and columnist after columnist, said I had no business running Logan. Some even went so far as to say that Logan was targeted because of me. Other airports had been compromised, too, but mine was the one whose planes took the towers down.

The long way down

It just got worse from there. The governor at the time, Jane Swift, forced me to resign six weeks later. It was either that or she was going to fire me. Then, the family of one of the victims sued me for wrongful death. That was absolutely shattering for me, to think that a widow and the mother of two children held me personally responsible for the death of her husband.

Nights were filled with horrifying dreams that I tossed and turned my way through. Peaceful sleep was a thing of the past. I feared that my name would forever be linked to that disastrous day, instead of what it used to be: a good, hardworking person—someone who would never dream of hurting someone else. And I kept wondering: Could I have prevented this? Were the deaths of all those people my fault?

While those around me urged me to move on, to put it behind me, I wondered how moving on from something so horrific as 9/11 was even possible. I didn’t know if I would ever find an answer to the question that haunted me endlessly: Was I to blame for this? The idea that I could end the pain was a powerful one. So much so that one evening, I entertained the idea of suicide. But instead, I listened to the voice within that told me to hang on. It was incredibly difficult to do.

Ultimately, the wrongful death case was dropped, but the suit against Logan lasted ten years. It was a long time, and it felt every bit of it.

The quest for redemption

When the 9/11 Commission Report was compiled, I testified before the Commission investigators, a panel authorized by Congress. I said, “If you find that Logan security was no different than any other airport that day, please say that. Say it for all of us feeling this burden.” It was their first footnote on the report—that Logan International Airport security had been no different than any other airport that day. Still, it wasn’t enough to help me move forward. I wanted some form of external exoneration, like for the president or someone else to say something about it. I wanted to know that others finally saw that I wasn’t to blame and that there was nothing I could have done to stop those planes from hitting the towers.

Being the hero in our own stories

The only thing that saved me was listening to myself. I had to listen to the belief I held within that I could not have done anything else. The security at Logan on 9/11 was exactly the same as it was at every other airport in America that day. None of us could have foreseen that planes themselves would have ever been used as weapons.

This entire experience has shown me that when terrible things happen, it’s scary. We want to blame someone for it; it makes us feel safer somehow. But that’s really no different than blaming a crime victim by saying she wore the wrong thing and that it wouldn’t have happened if she didn’t. I have also realized that it’s so hard—especially as a woman—to be your own hero. We tend to want someone else to come in and be the hero for us. But we can be the hero we need and save ourselves—we have it within us.

Moving beyond brokenness

I had my daughter the spring after I resigned, and about a year later, I began looking for work again. I’ve always defined myself by my work, but I needed to find a new career path. I have always loved writing—getting paid to choose the correct words is such a joy—and I couldn’t believe it when I got a job writing for the Boston Herald. Unfortunately, that became controversial because of my political past. Several writers there signed a petition for my termination, but I ended up working there for four years until I made the move to the private sector, working in public affairs.

Over that period of time, I just felt a sense of failure. I was failing to heal emotionally and mentally. I realized that our cultural definition of resilience isn’t a good fit for everyone. There’s this idea that you can bounce back better than ever, like the trauma never happened, but that isn’t true for all of us. It certainly isn’t true for me.

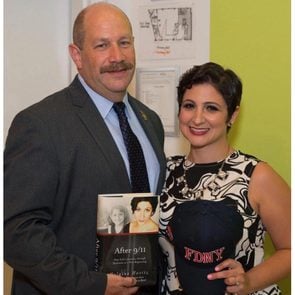

The lessons in sea glass

I wrote the book On My Watch (which will be released on April 14, 2020) to give meaning to it all. If one person finds that it helps them through a difficult time, then writing it was worth it. In terms of getting through trauma and ultimately healing, I often think of sea glass. It begins with a bottle broken by waves but eventually turns into something beautiful. I felt very broken for a long time, but I am still able to bring beauty to this life I live. I want people to know that in order to really get through something, you have to accept that you are forever changed. But you also need to know that you can carry joy right next to your pain and still have a wonderful life.

Next, read about the questions people still have about 9/11.