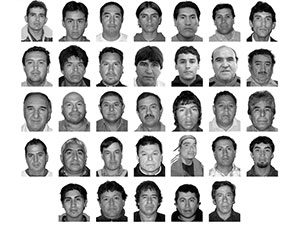

33 Miners, Buried Alive for 69 Days: This Is Their Remarkable Survival Story

Updated: Feb. 07, 2023

Almost half a mile underground for 69 grueling days, a group of Chilean miners hangs on to hope. Here is the incredible true story of their ordeal and rescue.

The ramp, the main tunnel in the San José Mine in Chile’s Atacama Desert, begins about a mile above sea level near the top of a round, rocky mountain. From the 16-by-16-foot entrance, the Ramp corkscrews into the mountain through a series of gradually narrowing switchbacks. Men driving dump trucks, front loaders, and pickup trucks use the winding path to gather minerals collected by the workers who mine small passageways for ore-bearing rock.

The ramp, the main tunnel in the San José Mine in Chile’s Atacama Desert, begins about a mile above sea level near the top of a round, rocky mountain. From the 16-by-16-foot entrance, the Ramp corkscrews into the mountain through a series of gradually narrowing switchbacks. Men driving dump trucks, front loaders, and pickup trucks use the winding path to gather minerals collected by the workers who mine small passageways for ore-bearing rock.

On the morning of August 5, 2010, some men are working almost 2,500 feet below the surface, loading freshly blasted ore into a dump truck. Another group works about a hundred feet above them, fortifying a passageway, while still others are resting in the Refuge, a room carved out of the rock some 2,300 feet down. The Refuge, with its cinder block walls and heavy metal door, was supposed to be a shelter in the event of an emergency, but it also serves as a break room; fresh air is pumped in from the surface to offer respite from the heat.

A little after 1:00 p.m., Franklin Lobos is driving a pickup truck down to the Refuge, where a group of miners waits for a ride up to the surface for lunch. Another miner, Jorge Galleguillos, is riding with Lobos when, at about 2,000 feet below the surface, he suddenly says, “Did you see that? A butterfly.”

“What? A butterfly? No, it wasn’t,” Lobos answers. “It was a white rock.”

“It was a butterfly,” Galleguillos insists.

Lobos can’t believe a butterfly would flutter this far down in the dark. But he doesn’t argue. Suddenly, the two men hear a massive explosion. The passageway fills with dust as the Ramp collapses behind them, hitting the men as a roar of sound, as if a massive skyscraper is crashing.

Below them, the blast wave throws open the door to the Refuge, and the miners waiting on the Ramp for the lunch truck run into the room. Soon about two dozen men are huddled inside as the mountain caves in on itself. After a few minutes, as the noise dies down, the men decide to run for safety, heading out to the Ramp to try to scramble to the surface.

Luis Urzúa, the shift manager, and Mario Sepúlveda, who is operating a front loader, are near the Refuge when they hear a crash and feel the pressure wave that passes through the tunnel. Florencio Ávalos, Urzúa’s assistant, pulls up in a pickup truck and tells them that the mine is collapsing.

The three men quickly drive to the Refuge to pick up anyone there on lunch break, but the room is empty. Then they head downhill because hey know there are workers deeper in the mine. It’s Urzúa’s responsibility to get every man out.

About 150 feet below the Refuge, Mario Gómez and Omar Reygadas, two mining veterans, are loading gold-and-copper-laden rock into the back of a truck. They both feel a burst of pressure, but Reygadas just thinks the shift supervisor has ordered some routine blasting. When their truck is loaded, Gómez begins to drive toward the surface but gets only a few hundred feet before hitting a thick cloud of dust. Soon he can see only a few feet in front of his vehicle. He points his steering wheel straight, driving blindly. Then Urzúa appears in front of him, gesturing for them to stop.

Gómez and Reygadas jump into the pickup, and Ávalos manages to drive back up to the Refuge. The men trying to escape during a lull in the explosions have now retreated to the Refuge. When they see the truck, they rush toward it, squeezing into the cab and jumping into the back. “Go! Go! Let’s get out of here!” At the wheel, Ávalos heads toward the surface.

The truck sags under the weight of the men. When the dust once again becomes too thick to see through, Mario Sepúlveda gets out and walks ahead with his flashlight, guiding Ávalos forward. They meet up with several mechanics who have been working higher up in the mine, and they, too, climb aboard. Advancing farther into the dust, they meet the truck coming down with Franklin Lobos and Jorge Galleguillos.

Sepúlveda shines his light on the two men and sees the blood-drained look of mortal fear. Lobos and Galleguillos recount the collapse they just escaped. Then Urzúa orders them to turn around, and they all head higher up the spiral, more debris appearing on the roadway of the Ramp, as if they are getting closer to the scene of a battle.

Eventually rocks block their way, and the men get out and walk. Adrenaline and a vision of the midday sun at the top of the Ramp urge them up the arduous climb. They follow the lights of their headlamps and flashlights until the beams strike the gray surface of a stone slab. After the dust settles, the full size of the obstacle becomes apparent. The Ramp is blocked, from top to bottom and all the way across, by a flat, smooth sheet of the mountain, as tall as a 45-story building and weighing 700,000 tons.

NO WAY OUT

At five feet three inches tall, Alex Vega is the smallest of the miners. He slithers on his stomach and stares into a tiny opening beneath the immense gray stone. Vega tells the men he thinks he can squeeze through.

“No,” Urzúa says. He thinks it’s a crazy thing to do.

But Vega insists, and finally Urzúa tells him, “Just be careful.”

Vega squeezes his small frame into a crevice of jagged rock. With his lamp in hand, he crawls about ten feet into the crack, until he can advance no farther.

“There’s no way through,” he announces after he crawls out.

For some of the older miners, the sight of the stone and Vega’s words bring an overwhelming sense of finality. Some have been trapped in mines before, by rock falls that a bulldozer could clear in a couple of hours. But this gray wall is different.

Galleguillos thinks he’ll never see his new grandson, and he feels tears running down his cheeks. Gómez, who lost two fingers in a previous accident, realizes that he’s pushed his luck too far—first his fingers, now his life.

The trapped miners turn their backs on the curtain of stone and split into two groups. Eight men search the mine’s matrix of tunnels for a passageway to the surface. The main purpose of these shafts is to allow air, water, and electricity to flow into the mine. They are supposed to be fitted with ladders to provide an escape route, but the San José Mine is a shoestring operation. The owners have cut costs by ignoring some of the safety measures, meaning only a few of the chimneys have ladders.

The rest of the group heads back to the Refuge. As the two groups split up, Florencio Ávalos, the second in command, quietly tells one of the older miners, “Take care of the provisions. Don’t let the miners eat them yet, because we may be trapped for days.” He speaks softly because he doesn’t want to panic the men.

At the Refuge, the miners note that the connections to the surface—the electricity, the intercom system, the flow of water and compressed air—have been cut. The first few hours pass slowly, punctuated by rumbling stomachs and the continuing thunder of rocks falling somewhere in the dark spaces beyond the weak, warm light of their headlamps.

Meanwhile, the eight-man escape expedition drives a jumbo lifter to the chimney, opening a hole in the ceiling. Raising his head into the hole, Sepúlveda is surprised to see a ladder, built from pieces of rebar drilled into the rock. He begins to climb, with Raúl Bustos behind him. The dust makes it hard to breathe, and the walls are slippery with humidity. Halfway up, one of the rebar rungs breaks off, and the metal strikes Sepúlveda in the front teeth, sending a rush of blood into his mouth. He shakes his head in pain but keeps going.

Sepúlveda reaches the top of the chimney and sweeps the beam of his flashlight across the blackness. He stands up, and when Bustos reaches the top, they walk up the Ramp, hoping that after the next curve in the spiral, the route to the top will be open. Instead their light beams strike the shiny, smooth wall blocking their way. Sepúlveda feels the hope draining from his body, leaving him with a cold, clear vision of what is happening to them.

The two men turn and walk downhill, past the chimney they just scaled, and go around another curve to find the same gray wall blocking their path again. When they look for the next chimney opening, the one that might lead them up to a higher level, their flashlights reveal that in this one, there is no ladder at all.

“This way isn’t going to work,” Sepúlveda says. “What are we going to tell los niños?”

“Let’s tell them the truth,” Bustos says.

THE SEARCH FOR HOPE

At the bottom of the chimney, Sepúlveda and Bustos deliver the news to the small group of men. The Ramp is blocked on other levels too. There is no way out.

The men look at Urzúa, the shift supervisor, but he says nothing. He looks drained and defeated. He knows that men are sometimes buried alive in mines and eventually die of starvation. And he knows that after six or seven days, if the rescuers don’t find you, they usually give up. He’d like to say something to give his men hope, but he refuses to lie to them. So he says nothing. Later, at the Refuge, Urzúa announces to the men that he is no longer their boss. They’re all stuck together, he says, and they should make decisions together.

Sepúlveda has a different attitude. His life has been one struggle after another—his mother died delivering him, and he grew up one of ten children of a hard-drinking father. Fighting to stay alive is when he feels most like himself. And so, despite his lack of standing in the mining hierarchy, Sepúlveda tries to take control of his own fate and that of the men around him with optimism and a focus on survival. When Urzúa and Sepúlveda and the men from the failed escape attempt arrive at the Refuge, they find a scene of disarray. Some of the hungry men have broken into the food supplies and grabbed packages of cookies and cartons of milk. They’re sitting in the darkness, crumpling plastic wrappers and chewing cookies.

“What are you doing?” Sepúlveda says with his raspy voice. “Don’t you realize we might be down here for days? Or weeks?”

Then he and Bustos reveal the truth about what they learned higher up in the mine. They are trapped. There will be no easy escape or rescue.

Sepúlveda leads a tally of what is inside the emergency cabinet—cans of peaches, peas, and tuna, along with 24 liters of condensed milk and 93 packages of cookies. But the men will not die of dehydration. There are several thousand liters of water in nearby tanks, to keep the engines cool. The water is tainted with small amounts of oil, but it is still drinkable.

A few men go back up to the caverns to try to alert people on the surface to the presence of men below—honking the horn of a front loader, banging the arm of the machine against the wall. They hear nothing in return.

Around 10 p.m., the men in the Refuge begin looking for a place to lie down. Omar Reygadas, a widower, thinks about his children and grandchildren. He begins to cry, so he steps out of the Refuge. He finds a front loader on the Ramp and sits inside, remembering the moment of collapse. Tons of rock have fallen, yet no one is hurt. He thinks it carries a hint of the divine.

Meanwhile, Urzúa has surrendered his authority, but he has not given up completely. Some of the men are restless and go back to the base of the chimney that Sepúlveda and Bustos climbed. They set fire to an oil-soaked air filter and a small tire, hoping the smoke will drift up and reach the surface, sending a signal that there are living men below.

They use a front loader to try to move the rocks in some of the galleries. Maybe if they clear a space, there will be an opening that leads upward. But every time they lift out rocks, more fall from the top of the pile.

At noon on the second day, all 33 men gather as Sepúlveda divides and distributes their daily “meal”—one teaspoon of canned fish mixed with water, and two cookies for each man. That single meal at noon, containing fewer than 300 calories, has to hold them until the next day.

SURVIVING UNDERGROUND

On the day the miners are trapped, men on the surface hear the explosions and see the dust spewing out from the mine entrance. One rescue team descends in a pickup truck until, about 1,500 feet below the surface, the men come to the flat gray mass of mountain blocking the Ramp. Another team brings ropes and pulleys to descend into the chimneys, but at each level, they find the same obstruction.

Calls go out to the local fire department, the National Geology and Mining Service, and the disaster office of Chile’s Ministry of the Interior. The mining company puts off contacting the families of the men, but wives and girlfriends and parents and siblings soon find out and congregate at the mine. Several times during the first few days, the mountain rumbles as if it is going to explode again.

Underground, the miners huddle inside the relative safety of the Refuge, making the heat and humidity even worse. The room fills with the smell of their sweating, unbathed bodies. They have no idea how long they’ll be down there, so they must conserve the water. It is too precious to use for bathing.

To keep from feeling hopeless, they talk and joke and tell stories. One miner, Víctor Segovia, starts a diary. “There is a great sense of powerlessness,” he notes. “We don’t know if they’re trying to rescue us, because we don’t hear any machines working.”

Another miner, José Henríquez is a devout Evangelical, and he leads the men in prayer. “We aren’t the best men, but Lord, have pity on us,” he says. They kneel and ask God to guide their rescuers to the tiny room where they are waiting.

Henríquez also has a cell phone. There is no service, but the men can use the phone to record events. Mario Sepúlveda narrates a short video of the men making a meal. “Tuna with peas!” he announces. “Eight liters of water, one can of tuna, some peas. So we can survive this situation.”

After the meal, a few of the men get excited because they say they can hear the sound of distant drilling. “It’s a lie,” someone replies. “You can’t hear anything.”

The discussion goes back and forth, until even those who say they felt that faint and possibly imaginary vibration concede that it has stopped, or has disappeared, or may have never existed.

Segovia writes in his diary that the men feel the monster of “insanity” welling up inside them. Four days underground now. He draws stick figures of the men lying on the ground; he lists the names of his five daughters and of his mother and father and himself and then circles a heart around them. “Don’t cry for me,” he writes.

At 7:30 p.m. on August 8, some 78 hours after being trapped, Segovia records the sound of something spinning, grinding, and hammering against the rock. A drill.

“Do you hear that?” Sepúlveda shouts. “What a beautiful noise!”

“Those drills can make 100 meters a day,” says one of the miners.

Everyone does the math. It will be another five or six days, if nothing goes wrong.

THE RESCUE PLAN

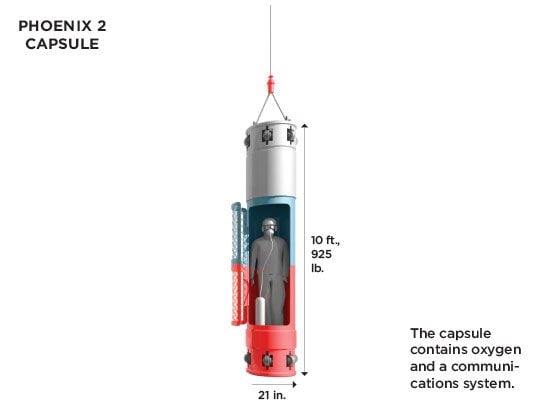

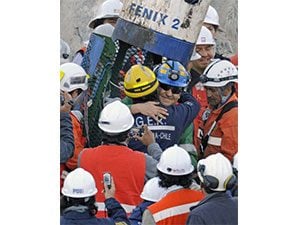

Once the plan was in place, it took a 46-ton drill more than a month to complete the nearly half-mile-deep rescue shaft. On October 12, 2010, Florencio Ávalos was the first miner to reach the surface in the capsule–painted white, blue, and red, the colors of the Chilean flag.

DESPERATE DRILLING

The first drill platform arrives at the San José Mine on Sunday, August 8, on a vehicle as long as a gasoline tanker. The rescuers consult the blueprints for the mine and begin drilling for the Refuge. The grinding and pounding spit a cloud of dust from a chimney pipe and send a flow of wastewater over the ground. Nearby, other teams begin to drill as well. Eventually nine drills will be working—rescuers are firing nine bullets at the target, hoping one will hit. A borehole to the Refuge would allow rescuers to deliver food and other supplies to the trapped miners.

By this time, all of Chile is watching. The country’s president puts his minister of mining in charge of the rescue effort, and the president him- self makes a visit to the mine. The drilling proceeds for a fourth, fifth, and sixth day. Shrines arise on the mountain, built by family members, with candles affixed to the rocks. Prayer is their only defense against the growing sense of hopelessness and finality.

The night of August 15, the miners’ 11th day underground, a drill hits an open space 1,653 feet below the surface but still about 650 feet above the Refuge. All the drills are halted as rescuers put their ears to a steel pipe they’ve lowered into the shaft. They hear a rhythmic noise, a tapping. A camera is sent down the borehole. There is nothing. Just a space of empty rock. The tapping sound? The power of suggestion. They want someone to be down there, and so they hear things that aren’t there.

The days pass, and pessimism grows. Some people say the miners are all dead. Others report strange occurrences—claiming to see spirits of the 33 men wandering around the neighborhood.

In the Refuge, some of the men play checkers with a set crafted from pieces of cardboard. They all tell stories; they talk about food. They conclude that if they die, their families might get between $80,000 and $120,000, or nearly a decade’s worth of wages for an average Chilean worker.

The drilling grinds on and then stops, often for hours at a time, leaving a cruel silence. Some men decide they can’t just sit and wait for the drills to reach them. The rescuers will eventually give up without a sign of life from below, the miners reason. So they renew their efforts to send a message to the top. They collect some dynamite and some fuses and walk up as high as they can. They wait for the drilling to stop. Then they light the fuse. The dynamite explodes—but they are 2,300 feet underground. How could anyone on the surface hear?

On August 16, the 12th day underground, Segovia notes in his diary the signs that they are losing hope: “Hardly anyone talks anymore. The skin now hugs the bones of our faces, and our ribs all show, and when we walk, our legs tremble.”

Their metabolisms are slowing down. Even the most energetic among them are sleeping longer than normal, and there is a haze drifting over their thoughts. Several men experience a strange side effect of prolonged hunger: Their dreams and nightmares are unusually long and vivid.

On the 16th day, the men share their last peach. Several men start writing farewell letters, in the hopes that a rescuer might one day find their final message. They are starting to feel weak. For some, it seems as if the next time they fall asleep, they might not wake up. Some need help to stand up and walk down the Ramp to go to the bathroom. The older miners, especially, are beginning to resign themselves to their fate. Only Omar Reygadas keeps insisting, “They’re coming for us.”

On the 17th day underground, the men hear another drill getting closer, the rat-a-tat-tat sound getting louder, holding the promise of either liberation or another disappointment. Segovia can’t allow himself to believe the drill will break through. Instead, he asks Sepúlveda, “What do you think dying is like?”

Sepúlveda says it’s like falling asleep. Peaceful. You close your eyes; you rest. All your worries are over.

A BREAKTHROUGH

At 6 A.M. on August 22, several men on the drill platform are asleep. But one driller notices something odd—the steel tube is starting to stutter. Suddenly the dust coming out of the chimney stops, and the pressure gauge drops to zero. He stops the drill.

Far below, there is a small explosion just up the tunnel from the Refuge. The grinding stops, and there is a whistling of escaped air. Two miners jump up and run toward the noise. They see a length of pipe protruding from the rock. A drill bit lowers and rises and lowers again.

One miner begins pounding with a wrench on the pipe protruding from the ceiling. He strikes it against the pipe with joy and desperation. We’re here! We’re here!

Soon all 33 miners gather around the pipe and the drill bit, embracing and weeping. José Henríquez, who, after 17 days underground, has been

transformed into a shirtless and starving prophet, looks at the drill bit and pronounces to everyone:

“Dios existe,” he says. God exists.

Up above, the drill operator feels the pulse in the steel and puts his ear to the shaft. He hears a frantic tapping. “It’s them!” he calls out.

The other drills on the mountain stop. Calls go out to Chilean officials. The drill team raises up the bit and removes the steel tubing from the shaft. The miners have painted the bottom of the tube. A note announces: “We are well in the Refuge. The 33.”

A camera and a microphone are lowered into the borehole, and soon the sound of the miners cheering and yelling comes over the speakerphone on the surface. The next tube lowered down contains small bottles of a glucose mixture. A note warns the miners not to drink it too quickly, but of course the men swallow it in one gulp, and several feel their stomachs cramp up painfully.

More glucose is sent down, along with medicines and eventually real food. Then the miners receive the first letters from their families.

On August 30, twenty-five days after the miners were trapped, the rescue team begins drilling a rescue hole. The plan is to excavate a 15-inch pilot hole, then widen it to 28 inches—room enough for a small capsule to bring the miners up one at a time. Because of the group’s location and the danger of another collapse in the 100-year-old mine, the rescue could take months. “God willing,” Chilean president Sebastián Piñera tells the men, “we’ll have you out before Christmas.”

THE NIGHTMARE ENDS

Sixty-nine days after the miners were buried, on the night of October 12, rescuer Manuel González descends in a capsule to coordinate the evacuation. Florencio Ávalos is the first to go up. “We’ll see each other up on top,” he tells the other miners as he enters the cage. Ávalos rises through the shaft. It takes 30 minutes to get to the surface.

Sixty-nine days after the miners were buried, on the night of October 12, rescuer Manuel González descends in a capsule to coordinate the evacuation. Florencio Ávalos is the first to go up. “We’ll see each other up on top,” he tells the other miners as he enters the cage. Ávalos rises through the shaft. It takes 30 minutes to get to the surface.

By the end of the next day, all 33 buried miners are brought to the surface. Rescuer González is the last man out. None of the men sustains serious injury, though most of them suffer lingering psychological and emotional issues—nightmares, depression, and alcohol abuse.

Today, most of those problems have begun to heal. The men received pensions from the Chilean government, enough that the older men could retire. Most of the younger miners are back to work, though, several in aboveground jobs with the national mining company; one is a truck driver, and another has a fruit business.

None of the miners got rich from their adventure or the publicity surrounding it. But they are all still alive.