Survival Stories: The Girl Who Fell from the Sky

Updated: Mar. 01, 2023

When she was 17, Juliane Koepcke dropped 10,000 feet into the Amazon rain forest. She describes how she survived—alone.

Juliane Koepcke grew up in Lima, Peru, before moving, at 14, to the Peruvian rain forest, where her parents, Maria and Hans-Wilhelm Koepcke, established the Panguana Ecological Research Station. After two years of accompanying them on research trips into the jungle, Juliane returned to Lima to complete high school.

Juliane Koepcke grew up in Lima, Peru, before moving, at 14, to the Peruvian rain forest, where her parents, Maria and Hans-Wilhelm Koepcke, established the Panguana Ecological Research Station. After two years of accompanying them on research trips into the jungle, Juliane returned to Lima to complete high school.

On December 24, 1971, Juliane, 17, and her mother boarded a flight in Lima bound for Pucallpa, the city with an airport closest to Panguana, to visit her father for Christmas. In her own words:

My days in Lima are wonderful. Despite my jungle experience, I am a schoolgirl. I spend my vacations in Panguana and my school days with classmates in Lima.

My mother prefers to fly to Pucallpa earlier, but a school dance and my high school graduation ceremony are on December 22 and 23, respectively. I beg my mother to let me attend.

“All right,” she said. “We’ll fly on the 24th.”

The airport is packed when we arrive the morning of Christmas Eve. Several flights had been canceled the day before, and hundreds of people now crowd the ticket counters. About 11 a.m., we gather for boarding. My mother and I sit in the second-to-last row on a three-seat bench. I’m by the window as always; my mother sits beside me; a heavyset man sits in the aisle seat. Mother doesn’t like flying. She’s an ornithologist and says it’s unnatural that a bird made of metal takes off into the air.

The first half of the hour-long flight from Lima to Pucallpa is uneventful. We’re served a sandwich and a drink for breakfast. Ten minutes later, as the flight attendants begin to clean up, we fly into a huge thunderstorm.

Suddenly, daylight turns to night and lightning flashes from all directions. People gasp as the plane shakes violently. Bags, wrapped gifts, and clothing fall from overhead lockers. Sandwich trays soar through the air, and half-finished drinks spill onto passengers’ heads. People scream and cry.

“Hopefully this goes all right,” my mother says nervously.

I see a blinding white light over the right wing. I don’t know whether it’s a flash of lightning or an explosion. I lose all sense of time. The airplane begins to nosedive. From my seat in the back, I can see down the aisle into the cockpit.

My ears, my head, my whole body are filled with the deep roar of the plane. Over everything, I hear my mother say calmly, “Now it’s all over.”

We’re falling fast. People’s shouts and the roar of the turbines suddenly go silent. My mother is no longer at my side, and I’m no longer in the plane. I’m still strapped into my seat on the bench, at an altitude of about 10,000 feet. I’m alone. And I’m falling. Check out this another story about a man who survived a plane crash.

We’re falling fast. People’s shouts and the roar of the turbines suddenly go silent. My mother is no longer at my side, and I’m no longer in the plane. I’m still strapped into my seat on the bench, at an altitude of about 10,000 feet. I’m alone. And I’m falling. Check out this another story about a man who survived a plane crash.

My free fall is quiet. I see nothing around me. The seat belt squeezes my belly so tight that I can’t breathe. Before I feel fear, I lose consciousness.

When I come to, I’m upside down, still falling, the Peruvian rain forest spinning slowly toward me. The densely packed treetops remind me of broccoli. I see everything as if through a fog before I pass out again.

When I regain consciousness, I’ve landed in the middle of the jungle. My seat belt is unfastened, so I must have woken up at some point. I’ve crawled deeper into the sheltering back of the three-seat bench that was fastened to me when I fell from the sky. Wet and muddy, I lie there for the rest of the day and night.

I will never forget the image I see when I open my eyes the next morning: The crowns of the giant trees above me are suffused with golden light, bathing everything in a green glow. I feel abandoned, helpless, and utterly alone. My mother’s seat beside me is empty.

I can’t stand up. I hear the soft ticking of my watch but can’t read the time. I can’t see straight. I realize that my left eye is swollen shut; I can see only through a narrow slit in my right eye. My glasses have disappeared, but I finally manage to read the time.

It’s 9 a.m. I feel dizzy again and lie exhausted on the rain forest floor. After a while, I manage to rise to my knees, but I feel so dizzy that I immediately lie back down. I try again, and eventually I’m able to hold myself in that position. I touch my right collarbone; it’s clearly broken. I find a deep gash on my left calf, which looks as if it has been cut by a rough metal edge. Strangely, it’s not bleeding.

I get down on all fours and crawl around, searching for my mother. I call her name, but only the voices of the jungle answer me.

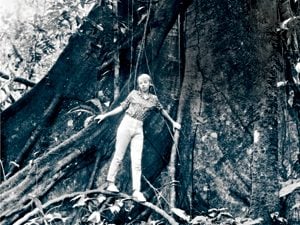

For someone who has never been in the rain forest, it can seem threatening. Huge trees cast mysterious shadows. Water drips constantly. The rain forest often has a musty smell from the plants that intertwine and ramble, grow and decay.

For someone who has never been in the rain forest, it can seem threatening. Huge trees cast mysterious shadows. Water drips constantly. The rain forest often has a musty smell from the plants that intertwine and ramble, grow and decay.

Insects rule the jungle, and I encounter them all: ants, beetles, butterflies, grasshoppers, mosquitoes. A certain type of fly will lay eggs under the skin or in wounds. Stingless wild bees like to cling to hair.

Luckily, I’d lived in the jungle long enough as a child to be acquainted with the bugs and other creatures that scurry, rustle, whistle, and snarl. There was almost nothing my parents hadn’t taught me about the jungle. I only had to find this knowledge in my concussion-fogged head.

Suddenly I’m seized by an intense thirst. Thick drops of water sparkle on the leaves around me, and I lick them up. I walk in small circles around my seat, aware of how quickly you can lose your orientation in the jungle. I memorize the location and markings of one tree to keep my bearings.

I find no trace of the crash. No wreckage, no people. But I do discover a bag of candy and eat a piece.

I hear the hum of airplane engines overhead. I look up, but the trees are too dense: There’s no way I can make myself noticeable here. A feeling of powerlessness overcomes me. I have to get out of the thick of the forest so that rescuers can see me. Soon the engines’ hum fades away.

I hear the dripping, tinkling, gurgle of water that I hadn’t noticed before. Nearby I find a spring, feeding a tiny rivulet. This fills me with hope. Not only have I found water to drink, but I’m convinced that this little stream will lead the way to my rescue.

I try to follow the rivulet closely, but there are often tree trunks lying across it, or dense undergrowth blocks my way. Little by little, the rivulet grows wider and turns into a stream, which is partly dry, so that I can easily walk beside the water. Around six o’clock it gets dark, and I look in the streambed for a protected spot where I can spend the night. I eat another candy.

On December 28, my watch, a gift from my grandmother, stops for good, so I try to count the days as I go. The stream turns into a larger stream, then finally into a small river. Since it’s the rainy season, there’s barely any fruit to pick, and I’ve sucked on my last candy. I don’t have a knife to use to hack palm hearts out of the stems of the palm trees. Nor can I catch fish or cook roots. I don’t dare eat anything else. Much of what grows in the jungle is poisonous, so I keep my hands off what I don’t recognize. But I do drink a great deal of water from the stream.

Despite counting, I mix up the days. On December 29 or 30, the fifth or sixth day of my trek, I hear a buzzing, groaning sound that immediately turns my apathetic mood into euphoria. It’s the unmistakable call of a hoatzin, a subtropical bird that nests exclusively near open stretches of water—where people settle! At home in Panguana, I heard this call often.

With new impetus, I walk faster, following the sound. Finally, I’m standing on the bank of a large river, but there’s not a soul in sight. I hear planes in the distance, but as time passes, the noise fades. I believe that they’ve given up, having rescued all the passengers except me.

Intense anger overcomes me. How can the pilots turn around, now that I’ve finally reached an open stretch of water after all these days? Soon, my anger gives way to a terrible despair.

But I don’t give up. Where there is a river, people cannot be far away.

The riverbank is much too densely overgrown for me to carry on hiking along it. I know stingrays rest in the riverbanks, so I walk carefully. Progress is so slow that I decide to swim in the middle of the river instead—stingrays won’t venture into the deep water. I have to look out for piranhas, but I’ve learned that fish are dangerous only in standing water. I also expect to encounter caimans, alligator-like reptiles, but they generally don’t attack people.

Each night when the sun sets, I search for a reasonably safe spot on the bank where I can try to sleep. Mosquitoes and small flies called midges buzz around my head and try to crawl into my ears and nose. Even worse are the nights when it rains. Ice-cold drops pelt me, soaking my thin summer dress. The wind makes me shiver to the core. On those bleak nights, as I cower under a tree or in a bush, I feel utterly abandoned.

By day, I go on swimming, but I’m getting weaker. I drink a lot of river water, which fills my stomach, but I know I should eat something.

One morning, I feel a sharp pain in my upper back. When I touch it, my hand comes away bloody. The sun has burned my skin as I swim. I will learn later that I have second-degree burns.

As the days wear on, my eyes and ears fool me. Often I’m convinced I see the roof of a house on the riverbank or hear chickens clucking. I am so horribly tired.

I fantasize about food, from elaborate feasts to simple meals. Each morning it gets harder to stand up and get into the cold water. Is there any sense in going on? Yes, I tell myself. I have to keep going.

I spend the tenth day drifting in the water. I’m constantly bumping into logs, and it requires a great deal of strength to climb over them and not break any bones in these collisions. In the evening, I find a gravel bank that looks like a good place to sleep. I doze off for a few minutes. When I wake up, I see something that doesn’t belong here: a boat. I rub my eyes, look three times, and it’s still there. A boat!

I swim over and touch it. Only then can I really believe it. I notice a beaten trail leading up the bank from the river. I’m sure I’ll find people there, but I’m so weak that it takes me hours to make it up the hill.

When I get to the top, I see a small shelter, but no people. A path leads from the shack into the forest. I’m certain that the owner of the boat will emerge at any moment, but no one comes. It gets dark, and I spend the night there.

The next morning, I wake and still no one has shown up. It begins to rain, and I crawl into the shelter and wrap a tarp around my shoulders.

The rain stops in the afternoon. I no longer have the strength to struggle to my feet. I tell myself that I’ll rest at the hut one more day, then keep moving.

At twilight I hear voices. I’m imagining them, I think. But the voices get closer. When three men come out of the forest and see me, they stop in shock.

“I’m a girl who was in the LANSA crash,” I say in Spanish. “My name is Juliane.”

Forestry workers discovered Juliane Koepcke on January 3, 1972, after she’d survived 11 days in the rain forest, and delivered her to safety. Ninety-one people, including Juliane’s mother, died in the crash of LANSA Flight 508. Juliane was the sole survivor. Now a biologist and librarian at the Bavarian State Collection of Zoology, Juliane returns to Panguana often, where the research station she inherited continues to welcome scientists from all over the world.