New Study: Cats Have 276 Facial Expressions

Updated: Nov. 18, 2023

Cats may play it cool, but their true feelings are written all over their furry little faces

The flick of an ear. A wrinkle of a nose. Those long, slow blinks. Cat owners have long believed their cats use body language to communicate their likes and dislikes. Now they have some science to back it up.

In a new study published in the journal Behavioural Processes, researchers identified a whopping 276 different facial expressions cats make when interacting with one another. “Cats are very expressive animals,” says study co-author Brittany Florkiewicz, PhD, an evolutionary psychologist at Lyon College in Batesville, Arkansas. “People who’ve had cats probably won’t be surprised by that, but what is surprising is the number of expressions they make, especially when you compare it to other species. Gibbons, for example, have only 80, while chimpanzees have more than 300. So cats have a very diverse and rich repertoire of facial expressions.”

While the study didn’t delve into exactly what each of those 276 expressions means, it does offer some clues into which ones are friendly and which are not, and this could help pet parents decode their cats’ behavior. Just be forewarned that the study focused on cat-cat interactions, not cat-human interactions, so you’ll have to look elsewhere for tips on translating the strange noises your cat makes and how to figure out if your cat is secretly mad at you. But here’s what the study just might reveal about your cat’s interaction with other friendly (or frisky) felines.

Get Reader’s Digest’s Read Up newsletter for more pet insights, humor, cleaning, travel, tech and fun facts all week long.

How did researchers conduct this study?

Florkiewicz and her co-author, Lauren Scott, studied 53 adult cats living at CatCafé Lounge in Los Angeles. “Cat cafes are perfect for this kind of research,” says Florkiewicz, “because the cats there can freely interact with one another and allow us to get these spontaneous, naturally occurring interactions.”

From August 2021 to June 2022, Scott spent approximately 150 hours visiting the cafe and collecting video of cat interactions using a handheld camcorder. She ended up with 194 minutes of facial-expression information. “Cats move very fast,” says Florkiewicz. “That was one of the obstacles: being able to anticipate the cat’s movements and being set to record when they have these spontaneous interactions.”

The researchers then coded the footage using Facial Action Coding Systems (FACS), a tool to identify subtle and overt facial-muscle movements, or “action units” (AUs). “Things like the pupils being dilated versus constricted, or the whiskers moving up, down, forward or backward, the ears moving forward or flattening, the corners of the lips going back, a wrinkle of the nose,” says Florkiewicz. “It’s the combination of those movements that create a facial expression, so by coding the video, we were able to identify all of these different facial-expression types and see which ones are associated with friendly interactions and which ones are associated with non-friendly interactions.”

What did the study reveal about cats’ facial expressions?

Florkiewicz and Scott identified 26 distinct AUs that were used to produce a total of 276 combinations. And while the researchers were impressed by the sheer number of facial expressions cats make—”it was surprisingly high,” says Florkiewicz—they were also struck by how many of the expressions were friendly in nature. Of the 276 expressions, 45.7% were seen in a friendly context, like when a cat was inviting another cat to play or groom, and 37% were seen when the cats seemed less friendly with one another, often accompanying aggressive or defensive behavior. (Around 17.4 % of the expressions were observed in both friendly and unfriendly contexts.)

The finding suggests that domestication probably played a part in helping cats develop their wide range of expressions. As domestic cats evolved, they had to learn to interact not just with humans but also other cats in multi-cat households. Even free-ranging, outdoor cats learned to congregate into colonies to afford themselves greater access to food sources and protection against predators. “Domesticated cats are very socially flexible compared to wild cats, who are very solitary,” says Florkiewicz. “Having a wide range of facial expressions was probably great for navigating different kinds of social interactions.”

What should you look for in your cat’s expressions?

While Florkiewicz and Scott have already been approached by developers who would like to turn their research into an app—kind of a Google Translate for cats—they say there’s still more work to be done before they can tell you which of those 276 expressions means “Play with me” vs. “Back away from my kibble bowl.”

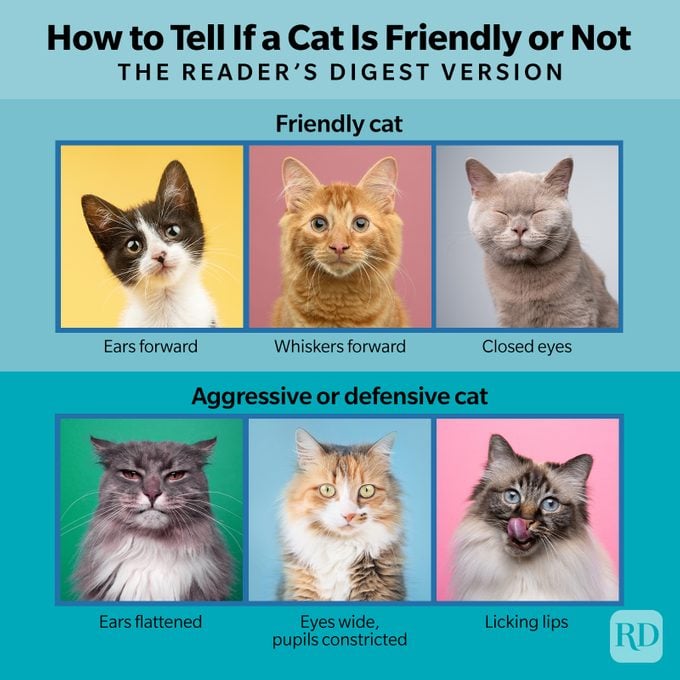

For now, though, Florkiewicz and Scott advise cat owners to look for a few key facial-muscle movements to determine if their cats are feeling friendly or not toward another cat. “It’s really the direction of the ears, the movement of the whiskers and the mouth, and also the constriction of the pupils that you really want to look out for when you want to know is this a friendly expression or a not-friendly expression,” says Florkiewicz. “For friendly interactions, cats will move their ears forward and their whiskers forward toward the other cat, and they also tend to close their eyes. During non-friendly interactions, we actually see the ears go backward, their eyes become wide and their pupils constrict, and they tend to lick their lips.”

How cat owners can use this information

Florkiewicz and Scott are already planning additional research studies on cat expressions in the hope of helping cat owners and cat shelters better understand the relationship between cats. “Our hope is that cat owners who are thinking of adopting a second, third or fourth cat will be able to use this information to assess the relationship that their cats have and help them make decisions about introductions and adoptions,” she says.

It’s already come in handy at home, where Florkiewicz, who adopted her first cat, Char, in 2022, recently introduced a second cat, Darth Vader, to the family. “I saw some of the same exact facial-muscle movements we observed in our study,” she says. “Char’s ears and her whiskers went forward when she was sniffing Vader. She was very curious. And then when he snuck up and pounced on her, her ears went back, her pupils constricted and she licked her lips, and I was like, ‘OK, time to separate!’ It was a great way to assess what stage of the introduction process Char was comfortable with. And I hope other people find it helpful too.”

About the expert

- Brittany Florkiewicz, PhD, is an evolutionary psychologist at Lyon College in Batesville, Arkansas, and the co-author of the article “Feline Faces: Unraveling the Social Function of Domestic Cat Facial Signals,” published in Behavioural Processes in October 2023.

Sources:

- Behavioural Processes: “Feline Faces: Unraveling the Social Function of Domestic Cat Facial Signals”

- AnimalFACS: “CatFACS”