These Four People Were Faced with Death and Lived to Tell Their Stories

Updated: Nov. 07, 2022

When faced with certain death, you need bravery, determination, and plenty of luck.

You never know when your life is about to change forever. It can happen any day, at any moment, and for some people, that life-changing moment is a life-or-death situation. That was the case for this hiker who fell off a cliff and the expert skier who faced an avalanche, as well as the four people in the following stories. They survived everything from being swallowed by a whale to being swept away in a mudslide. Maybe it was quick thinking, a strong survival instinct, or simply fate, but their survival stories are truly nothing short of a miracle.

I survived being swallowed by a whale

Julie McSorley, 56, physical therapist

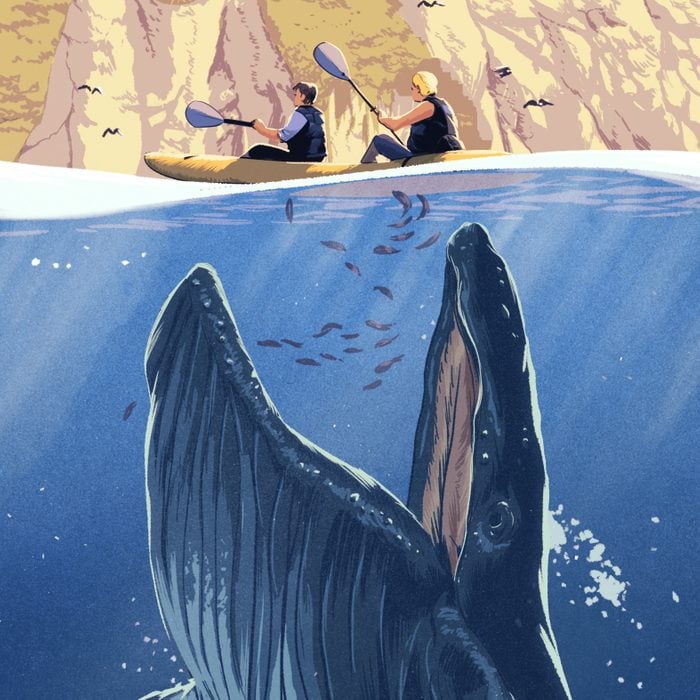

I live with my husband, Tyrone McSorley, in San Luis Obispo, California, about three miles from the beach. Every few years, the humpback whales come into the bay for a few days while they’re migrating. November 2020 was one of those times, so we took out our yellow double kayak to watch the wildlife. We paddled out the length of the pier and saw seals, dolphins, and about 20 whales feeding on silverfish. We were in awe watching these graceful behemoths—each one about 50 feet long—breach and spray through their blowholes. We laughed when they turned their side fins so that it looked as if they were waving at us.

At the time, my friend Liz Cottriel was staying with us. The next day, I asked her if she wanted to go out on the water to see them.

“No way,” said Liz, now 65. She was not an experienced kayaker and was terrified that the kayak would overturn while we were surrounded by hungry whales. “There’s nothing to worry about,” I assured her. “The craft is stable, and we can turn back anytime.” After some cajoling, she finally agreed to join me. I didn’t want her to miss this magnificent experience and regret it later.

Liz and I got out on the water at 8:30 the following morning. There were already about 15 other kayakers and paddleboarders in the bay. It was warm for November—about 65 degrees— so we wore T-shirts and leggings. After a half-hour, we had our first whale sighting just past the pier: two humpbacks swimming toward us. How amazing to be that close to a creature that size, I thought as the whales dipped under the waterline.

When whales go down after breaching, they leave what looks like an oil slick on the water. I figured if we paddled toward that spot, we’d be safe from the whales, since they’d just left. We followed them at a distance—or what I thought was a distance. I later found out that it’s recommended to keep 300 feet away. We were more like 60 feet away.

Suddenly, we were being pelted. A tightly packed swarm of fish, known as a bait ball, started jumping out of the water into our kayak. Their movement sounded like crackling glass all around us.

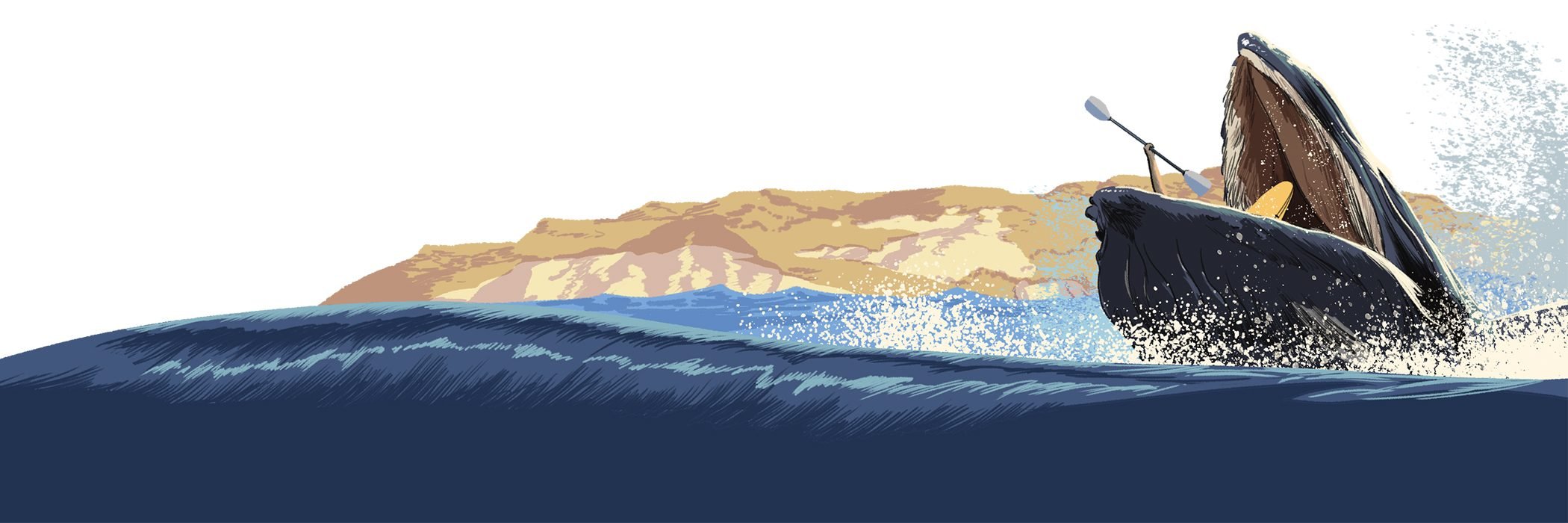

What should have been a comical moment was actually terrifying. Their actions meant they were escaping the whales, which meant that we needed to get out of there too. But before we could paddle to safety, our kayak was lifted out of the water about six feet, bracketed by massive jaws. Liz and I slipped out of the kayak into the whale’s mouth. My body was engulfed except for my right arm and paddle. Liz, meanwhile, was looking up directly at the whale’s upper jaw, which she later described as a big white wall.

As the whale’s mouth closed, Liz thrust her arm up to block it from crushing her. I felt the creature begin to dive and had no idea how deep we’d be dragged. Still, I didn’t panic. I just kept thinking, I’ve got to fight this. I’ve got to breathe.

Whales have enormous mouths but tiny throats. Anything they can’t swallow, they spit right out. That included us. As soon as the whale dipped under water, it ejected us, and we popped back up onto the surface about a foot apart. The entire ordeal lasted only about 10 seconds.

A few kayakers paddled over. One was a retired firefighter, who asked us if we had all of our limbs. “We thought you were dead!” he said.

We were not, of course. But I am much more aware of the power of nature and the ocean than I was before. Liz was shaken up, likening the ordeal to a near-death experience, and she says her whale-watching days are over. But even she had to laugh when she got home that afternoon and realized she’d brought back a souvenir. When she pulled off her shirt, six silverfish flopped out.

—As told to Emily Landau

I survived falling in quicksand

Ryan Osmun, 37, photographer

It was February 16, 2019, at 8 a.m. when my girlfriend, Jessika McNeill, and I arrived at Utah’s Zion National Park. We’d traveled from our home in Mesa, Arizona, to hike the nine-mile-long Subway Trail, so named because of its stunning tunnel-shaped canyon. Halfway through our trek, which included climbing over boulders and fording streams, the sunshine gave way to a light snow. Soon after, we reached the rust-colored walls of the Subway Trail. A small pond stood in our way, with the trail continuing on the other side. Because the pond looked shallow, we began to wade through, with Jessika leading the way.

About five feet from the edge, her front foot sank into the sandy bottom. Then she fell forward and both legs started to sink. I lunged, grabbed her under the shoulders, and pulled her out of the muck. She scrambled back to shore. But now I was sinking. The muck came all the way up to my right thigh and my left calf. I freed my left leg but couldn’t budge my right.

Jess handed me a long stick we’d picked up earlier in the hike. I jammed it down the side of my leg and tried to wiggle and pull it out. Nothing. I was mired in quicksand.

Jessika started scooping sand with both hands, but it was refilling faster than she could pull it out. “Don’t bother,” I told her. “You’re just wasting your energy.” While I was no longer sinking, I wasn’t getting out, either.

We couldn’t call for help because the only cell reception was back at the trailhead, five hours away over rough terrain. I told Jessika she had to hike back and call for help. She was scared—she had only ever hiked with me and was wary of hiking alone on a trail the National Park Service calls “very strenuous.” But we were out of options.

Thirty minutes after she left, it started to snow heavily. I zipped up my jacket and pulled my head inside. At some point, I nodded off to sleep. I don’t know how long I was out, but I woke up with my upper body slipping backward into the quicksand. I quickly planted my stick into the dry ground, stopping my fall.

I was exhausted. If my entire body ever did fall in, I’d never get out. It had been about five hours since Jess left, and it was getting dark.

A few hours later, I saw a light through my jacket. I prayed it was a helicopter, but it was the moonlight shining over the canyon walls. At that point, I was soaking wet and knew I wasn’t going to make it. I started to think about what I could do to die faster. But I didn’t want to drown if I fell backward again. That would be the worst way to go.

An hour later, another light shone across my eyes. A flashlight! I yelled for help. A man hollered back as he ran to me. He said that his name was Tim and that Jessika had gotten through to rescuers. He had hiked up, and the rest of his crew was an hour behind him.

When the three others arrived, they set up a pulley system to yank me out, tying an anchor strap around a boulder. Two of the rescuers held me under each shoulder as Tim wrapped a strap around my kneecap. A fourth rescuer worked the pulley. With each ratchet, it felt as if my leg was being ripped off. Tim dug into the sand and got a hand around my ankle and started pulling up. It was agonizing, but I could feel my leg moving. “Keep going!” I screamed.

Three more ratchets and my leg was freed. My rescuers dragged me to the side of the canyon because I couldn’t walk. I couldn’t even feel my leg.

It was too dark and snowy for a helicopter, so they got me into a sleeping bag and gave me pain medication. Then we settled in for the night.

When I woke up at 6 a.m., snow covered the top of my sleeping bag, and flakes were still coming down. Around noon, the weather lifted, and my rescuers called in a helicopter.

My entire leg had swollen to the size of my thigh, but when I got to the hospital in St. George, X-rays revealed no fractures or breaks. I had sat in the quicksand for 12 hours and thought for sure I would die. But I didn’t.

—From Outsideonline.com

I survived falling off a mountain

Gurbaz Singh, 18, student

When I was 13, I climbed my first mountain—a fairly gentle 3,900-foot peak near where I live in Surrey, British Columbia. I was overweight at the time and out of breath when I reached the summit. But I loved the challenge of conquering something bigger than myself. Soon I’d climbed nearly 100 peaks. My parents were happy I’d finally found a hobby.

I often go climbing with my friend Mel Olsen, whom I’d met in a Facebook group. Two years ago, on December 30, when I was 16, she and I drove to Oregon to tackle 11,240-foot Mount Hood.

It’s safer to start winter climbs at night when there’s less risk of the sun melting the snowpack. That day, we started at 3 a.m., following the paths alongside the ski runs. The temperature was about 14 degrees, and we wore layers we could easily remove, knowing the exertion would make us warm. Along the way, we met two other climbers, and the four of us continued on together.

After about five hours, we reached Devil’s Kitchen, a plateau at about 10,000 feet, just before the final push to the top. By this point, the wind conditions were nasty. My exposed skin felt as though it were burning. The other climbers decided to turn back, but Mel and I went ahead. We had ice axes, helmets, and crampons (ice cleats). We were prepared for the climb.

The trail we followed grew narrower and steeper. At around 9 a.m., we reached a patch of ice called an ice step. It was about three or four feet tall and sloped at a 75-degree angle. I volunteered to go first. I placed my left foot on the ice step.

You gain a sense of the ice when you stick your ax and crampons into it, and it felt good. Confident I was safe, I put my full weight on it. Suddenly, I heard a crack, and a whole slab of ice broke off the step, right under my foot.

In an instant, I fell backward. I could hear Mel calling my name as I tumbled down, bouncing off the rock face and rolling down the mountain as if I were a character in a video game. I remember thinking, This is it. You’re done.

I stuck out my arms and legs, grabbing at anything. That stopped my somersaulting down the mountain, but I was still sliding. After a few seconds, I came to a stop on a shallow incline just above the Devil’s Kitchen. I’d fallen 600 feet. My clothes were shredded, my helmet was broken, and my face was bloodied from cuts and scratches.

I wanted to make sure I had all my faculties, so I asked myself: Where are you? Mount Hood. What’s the date? December 30. Good. My brain wasn’t scrambled.

Then I took a survey of my body to see where I was hurt, starting with my head, then my neck and arms. For the most part, I was fine, except that I was suffering from a sharp, agonizing pain in my left leg.

Later I’d learn that I’d fractured my femur and that the bone was slicing into my skin and muscle. Oddly, when I touched my left leg, I couldn’t feel anything, so I frantically tried wiggling my toes. Fortunately, that worked—at least I knew I wasn’t paralyzed.

As Mel made her way down, I yelled for help, and other climbers came to assist me. A couple of them were trained EMTs. They splinted my leg and called Portland Mountain Rescue. Mel stayed by my side while I tried not to cry from the pain.

I’d been lying on the ice, shivering and in agony, for four hours by the time the rescuers reached me. They strapped me onto a sled and pulled me down the mountain. I have a pretty high pain tolerance, but I screamed with each bounce.

At the bottom of Mount Hood, I was loaded into an ambulance and taken to a hospital, where I stayed for four days. The doctors told me it would be a year before I could climb again, but I was back on the trails within six months.

The fall has made me more cautious. One slip on a mountain can change everything. But the experience also made me grow as a person. There was a lot of media attention following the accident; strangers commented on the videos, calling me vile names and saying I’d put others in danger. Some said I should go back to India. I think handling all that at such a young age helped me mature.

Since the accident, I’ve climbed another 60 mountains. I’m not going to let one fall and its aftermath keep me from doing my favorite thing in the world.

—As told to Emily Landau

I survived being caught in a mudslide

Sheri Niemegeers, 47, investment administrator

It was May 2018, and my partner, Gabe Rosescu, and I were taking a road trip in his little Hyundai Elantra from my home in Weyburn, Saskatchewan, to visit friends in Nelson, British Columbia. It was our first trip together after six months of dating, meaning it would be an adventure on so many levels.

At around 5:30 p.m., we were driving along the Crowsnest Highway, a steep winding road that cleaves through the southern Canadian Rockies. I was texting my mother when I happened to look up in time to see an enormous tree in front of us on the highway—standing straight up! It was being pushed along by a torrent of mud that was gobbling everything in its path. We didn’t know about the recent flooding in the area, and now we were literally in the thick of it.

Gabe and I shot each other a look and said, “Oh, shoot.” Understatement of the century. Within seconds, our car was somersaulting 900 feet down the cliffside.

I don’t know how long we were unconscious, but I woke up to the sound of Gabe moaning. He was slumped over the steering wheel, and his blood was everywhere.

The car had landed on a small ledge amid trees that had come down with the slide. On one side of us was the mountain. On the other, a steep drop of about 3,000 feet into a river.

I tried opening my door and was overcome by excruciating chest pain. I’d later learn that I’d suffered a broken sternum. In addition, my left ankle had been crushed, and my foot was practically turned sideways. Gabe had broken his nasal and cheek bones, as well as his orbital bones, leaving him blind in his left eye. Parts of his skull were crushed, and his scalp was nearly ripped off.

With the passenger and driver’s side doors crushed shut, and my window impassable, the only way out was through the driver’s side window. Neither of us remembers doing it, but somehow we both managed to crawl out of that wreckage.

We sat on a log and considered our options. We had no phone signal, and it was 900 feet straight up back to the highway. All we could do was yell for help.

Incredibly, someone responded. Four bystanders had spotted our car and were wading through the mud to us. Once they arrived, two of the men helped Gabe shimmy up the hill. Because of my injured foot, the other two had to carry me, with one man grasping me below my armpits and the other holding my legs. It was tough going. They went as far as they could until one of them sank into the mud. They then passed me off to the other two men who’d been helping Gabe. Those men carried me while the unstuck man pulled his partner out of the mud. The second pair carried me until one of them sank into the mud and they passed me back off to the first two. This went on for about an hour: Carry me. Sink into the mud. Hand me off. Pull the other out.

By the time we reached the highway, at around 7 p.m., Gabe was in shock. He kept slipping in and out of consciousness. When the EMTs arrived soon after, they let us kiss goodbye from our stretchers before loading us into separate ambulances. I didn’t think I’d ever see my boyfriend again.

I went to a nearby hospital, and Gabe was eventually airlifted to a trauma hospital 260 miles away. Along the way, they kept shocking him to keep him awake so he wouldn’t slip into a coma.

Gabe would be hospitalized for six weeks following surgeries to reattach his scalp. I was released 10 days after my surgeon reconnected the main artery in my left foot. I’ll walk with a limp for the rest of my life, and Gabe permanently lost the vision in his left eye. Otherwise, we’re fine.

Before this all happened, we were happy-go-lucky people. Oddly enough, the accident and improbable rescue has made us even more positive. We’re grateful to be alive. The experience also bonded us as a couple, and we haven’t stopped taking road trips. A year after the accident, we drove back to the Crowsnest Highway and gave the finger to the mudslide.

—As told to Emily Landau