As Book Banning Increases, Librarians Are Banding Together to Fight Back

Updated: Jan. 25, 2024

Librarians are on the front lines of the book-banning battle, but they're not giving up without a fight

Martha Hickson knows why reading is important. In her 17 years as a high school librarian, she’s watched over and over as books have helped young people find language to describe their lived realities and exposed them to lives and worlds beyond their own. So she was puzzled when, in September of last year, a group of parents asked the local board of education to ban two titles from her library: Gender Queer by Maia Kobabe, and Lawn Boy by Jonathan Evison. One parent even called Hickson out by name in her testimony at a board meeting, upset that Hickson had “let” her 16-year-old son read books by and about queer people.

When Hickson went to investigate why this was happening, she discovered that these challenges weren’t isolated incidents—they were part of a coordinated movement advocating book banning, which has, in her words, “spread like a fungus nationwide.” Organized and connected by the internet, parent groups are aiming to ban books by Black authors, LGBTQ+ books and plenty of young adult titles. These bans aren’t about literary merit; some of the best books have become banned books because people object to their content.

As far as Hickson is concerned, banning books is tantamount to professional malpractice. “First, the whole idea of being upset about ‘letting’ a student check out a book confuses me,” she said in a recent email. “It’s a library, the purpose of which is to allow readers to independently select reading material. ‘Letting’ people check out books is the whole point.”

But beyond that, she adds, “when I order books for the library or create a book display, I’m mindful about making sure that the whole community of kids in the school can see themselves represented—not just so they can read about people like them, but also so they can experience lives that are different from their own. That’s called education.”

There’s been a nationwide rise in book bans in the past few years; the number of bans went up by 14% between 2018 and 2019 alone. These actions have pushed librarians into an uncomfortable spotlight as their fight to freely distribute information is met with legal attacks at work as well as tactics that sometimes hit closer to home. But they aren’t taking it lying down. From forming banned book clubs to advocating for legislation that will protect them and their workplaces, librarians are pushing back on people and organizations that try to ban books.

Join the free Reader’s Digest Book Club for great reads, monthly discussions, author Q&As and a community of book lovers.

The rise in book banning

Book banning is hardly new. In fact, many classic books were first banned centuries ago.

One of the first books to be the subject of a widespread ban in America was Harriet Beecher Stowe’s Uncle Tom’s Cabin, which was published in 1852 and depicted the life of enslaved Black people in the pre-abolition south. Because it ignited a debate about slavery, and even inspired sympathy for Black people, it was barred from being sold in Confederate states. Books about race relations in America have been a frequent target of bans ever since.

Then came the 1873 Comstock Act, which prevented the distribution of “pornography” through the mail. Explicit sexual material wasn’t the only thing that got caught up in its dragnet. Court cases in the ’30s and again in the ’50s loosened the legal definition of obscenity and gave us the relative freedom to send, read and sell books that we enjoy today.

But there are occasional waves of increased repression, as happened in the late ’70s and early ’80s. In 1982, the American Library Association created Banned Books Week, an attempt to bring attention to the issue and demonstrate that challenged and banned books had enormous literary and social merit. At that time, the organization reported 700 to 800 challenges to books per year. In 2021, that number was closer to 1,500 books. To get a sense of where you fall in the history of book banning, check out a list of books banned the decade you were born.

This movement to ban books is being led by a small but vocal minority. A recent American Library Association survey found that most voters across the political spectrum oppose efforts to remove books from libraries. But it’s those who are in favor of bans who are working hardest to get their voices heard.

Librarians under attack

It’s not just books (and the students who want to read them) that are affected by book banning. This latest wave of bans comes with a side of personal rhetoric that has made it hard for librarians to feel safe in the profession—and sometimes even in their homes.

Hickson was accused of being a sex offender. The parents who objected to the reading material she provided for students contacted law enforcement, sent her hate mail and smeared her on social media. “It all became so intense that I experienced a physical and emotional breakdown on the job in mid-October 2021,” she says, “which resulted in my doctor removing me from the workplace for several weeks, prescribing anxiety medications and referring me to a therapist.”

This isn’t an uncommon outcome. “Many school librarians are nervous coming into the school year, given the attacks and threats that are being made on librarians and teachers as well as the increasingly personal natures of those threats,” says Peter Bromberg, associate director of political action committee EveryLibrary. “We have armed individuals and groups showing up at school board meetings, and the extreme rhetoric coming from some politicians is stoking the fires. I would not be surprised if we saw a wave of resignations and retirements over the next year if these threats continue.”

And Louisville Free Public Library director Lee Burchfield says that while the library system he oversees hasn’t been deeply affected by the recent rise in challenges to books, he’s aware of the increasing attacks on librarians across the country and how it’s affecting people in the profession. “As a library professional, it is discouraging,” he says. “It seems like such a simple concept—to check out and read the materials you want to read and allow others to do the same. I think, personally, it’s just shocking and disappointing that anyone would think book banning is a good idea.”

But some librarians remain unbowed. “Every librarian I’ve spoken to who’s within striking distance of retirement is weighing whether to stay,” Hickson says. “I’m no exception. I’ve thought about leaving, but at this stage of my career, it’s just not practical. Leaving now would reduce the income on which my retirement plan is based, and I’m just not willing to have book banners pick my pocket for the rest of my life. So I’m going to try to stick it out and ride this wave of censorship. It’s got to end sometime.”

The book banning effect

Every day Hickson stays at her job is a day that her students have access to diverse books. And those can have a life-changing impact. “We have many books about sensitive subjects that affect teens: substance abuse, anxiety, depression, divorce, sexuality, eating disorders,” Hickson says. “Banning those books from a library doesn’t take those issues out of society or out of teens’ lives.”

In other words, stocking feminist books, Native American books, Asian American books and books by Latinx authors—among many others—isn’t a political agenda. It’s just an attempt to reflect students’ reality outside of the library’s walls.

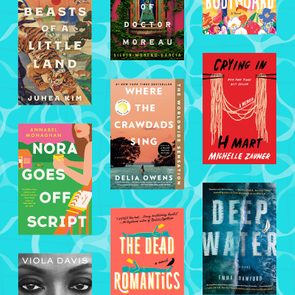

When she thinks of what these books mean to their readers, Hickson recalls an Asian American student reading Michelle Zauner’s Crying in H-Mart on her recommendation … and then returning to renew the book so that his mom could read it too. She thinks of the student who checks out every freshly acquired LGBTQ+ book that appears on the New Arrivals shelf. “The joy on her face and the excitement in her voice were so sweet,” Hickson recalls.

And while Hickson was fighting the challenges to Gender Queer and Lawn Boy, a former student reminded her of why the battle against book bans is crucial. “He’s now pursuing a doctorate in psychology and told the board how important it is for LGBTQ+ students to have books available in the school library,” she says. “When he came out in high school, he was kicked out of his home and taunted by fellow students in the classroom. Reading books about gay life wouldn’t have been safe for him at home. The school library was the only place he could safely access the reliable information he needed.”

Without those resources, her student would have been isolated, alienated and potentially unsafe.

Librarians fighting back

Librarians and their systems are combating censorship in every way they can. It starts with the challenges themselves.

“We have not banned any titles [at the Louisville Public Library],” Burchfield stresses. “I want to be clear about that. When we receive a formal challenge, we evaluate the item to see if it fits the parameters of our selection policy. So far, all the items that have been challenged have been found to do so.”

All the challenged books have met the Louisville Free Public Library’s selection policy. And so those books have remained available to the public.

“Librarians are fighting back against book challenges by showing up every day and simply doing their jobs,” Bromberg says. “It’s not flashy, but school librarians and library directors across the country are doing the important work of talking to their community, helping their boards understand the mission of the library, the importance of following policy and defending the First Amendment rights of all community members and all students.”

He also points to an increasing number of grassroots groups led by parents and citizens that are organizing locally and statewide—like banned book clubs, where students meet to read frequently banned books and discuss them together, and the Texas-based Freadom campaign, which promotes the freedom to read.

“EveryLibrary provides pro bono help to these groups, coaching them on how to effectively show up and speak up at board meetings and legislative hearings, and how to offer a strong defense of first amendment rights and counter the un-American efforts to remove the voices of BIPOC and LGBTQ+ authors from our shelves,” says Bromberg, who encourages anyone in need of such support to reach out to EveryLibrary.

Hickson says she definitely feels the support from within and outside the library world. “Librarians are a tight-knit community,” she says. “To help me, librarians from throughout New Jersey and nationwide wrote to the board, and some spoke at board meetings. Around the country, some librarians have spoken to the media to get the word out.”

And they do it even though they face potential backlash—the sort of threats and smear campaign Hickson experienced.

Fight for your right to read

Book banning may have the most obvious effect on students and librarians, but it’s an issue that affects us all. When kids can read widely, they expand their worldview and become better, more empathetic humans who have a greater potential to change the world. As frequently banned author George M. Johnson told Reader’s Digest, a book is “a tool that helps youth understand that other people exist outside of them—and that some of them have a privilege that can help those people. So maybe when they become the leaders, the systems they create and build will be encompassing of everyone because they have learned about other people.”

With that in mind, everyone who cares about preserving the right to read needs to exercise their right to vote for people who oppose book bans.

“There’s only so much librarians can do on our own,” Hickson says. “We need community voices and community support. The next few months, leading up to the November election, will be crucial. Libraries and librarians will continue to be targeted as a means to manufacture outrage among some voters. Those who value the First Amendment right to read need to fight back.”

She encourages everyone to “show up at school board and library board meetings. Speak up to demand that readers retain the right to make their own choices. And most important, vote in November, paying special attention to candidates’ views on intellectual freedom at all levels of the ballot, from school board on up.”

Shop banned books

Sources:

- Martha Hickson, high school librarian in New Jersey

- Peter Bromberg, associate director of EveryLibrary

- Lee Burchfield, director of the Louisville Free Public Library

- American Library Association: “Banned and Challenged Books”

- Freedom Forum Institute: “Book Censorship”

- American Library Association: “Voters Oppose Book Bans in Libraries”