A Deep Sea Diver Went Out on a Routine Job—Then His Air-Supply Cord Snapped 300 Feet Down

Updated: Nov. 24, 2022

It was supposed to be an easy job for a team of men who repair underwater pipelines.

Leaving his fiancée to go to work was harder for Chris Lemons than for most people. He is a deep-sea diver, typically away from home for four-week stints several times a year. This time he had a job replacing oil pipes at the bottom of the North Sea more than 120 miles off Aberdeen, in northeast Scotland. As Lemons, 32, got ready to leave that day in September 2012, he gave his fiancée, Morag Martin, the usual reassurances: “Don’t worry. It’s a carefully controlled environment.”

“I’ll miss you,” said Martin, 39. “But we’ll keep in touch all the time.”

The couple had met five years earlier at a party. Lemons, a six-foot-four-inch Englishman, was a diver and dive-boat crewman. He was drawn to Martin’s gregariousness, while she found him kind and funny. They started dating, and soon Lemons moved in with Martin. They lived frugally while he trained in specialized saturation (SAT) diving, a job that involves maintaining seabed pipes for the oil and gas industry. It has its risks, from decompression sickness to drowning—several SAT divers have died in recent decades around the world. But Martin knew how much it meant to him.

And it paid well, helping the couple plan an exciting future together. Martin had recently become the head teacher at a school in the Scottish Highlands, and they were building a dream house overlooking the sea. Their wedding was set for the following April.

At home, their conversations ranged from “What place settings shall we have at the reception?” to the complexity of house foundations.

They also talked about having children and later moving to France, where Lemons had family. It was a joyful time.

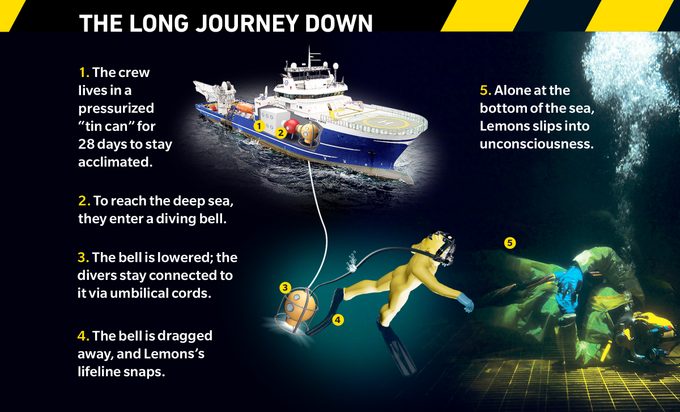

It’s called saturation diving because at the intense pressures found in the deep sea, gas that a diver breathes saturates the body. When the diver surfaces and the pressure drops, this gas can emerge as deadly bubbles in the blood and tissues, causing decompression sickness, or the bends. SAT divers reduce this risk by living full-time in a pressurized chamber in the dive ship.

For the September job, Lemons would be part of a three-man team sharing the SAT chamber with three other teams for a month aboard the 348-foot vessel Topaz. He was delighted to learn he’d be working with Duncan Allcock.

Allcock, 50, had been diving in the North Sea for 17 years. He worked with Lemons, who had qualified 18 months earlier, on his first few dives, becoming Lemons’s unofficial mentor. In a competitive industry with only short-term contracts, Allcock strove to make Lemons look good in front of supervisors, giving him advice and nudging him away from mistakes. “If you’re unsure about something, don’t worry. I’ll talk you through,” he’d reassured Lemons. Their third team member would be David Yuasa, whom Lemons knew by his excellent reputation.

For the first days in the chamber, the men chatted about Lemons’s house build, his upcoming wedding, and Allcock’s son, who’d just started working in diving. Lemons couldn’t properly speak to Martin—helium in the chamber made the divers’ voices high-pitched and distorted—but they kept connected by e-mail, and Martin sent pictures of her adventures cycling and climbing local mountains.

Just before 9 p.m. on September 18, it was Lemons’s team’s turn to dive. The three transferred to a diving bell, a smaller vessel for transport to the deep sea. The diving bell was lowered on cables to around 250 feet below the Topaz. Lemons and Yuasa would descend a further 50 feet to replace some pipe on a structure resting on the seabed. The men would be connected to the bell by umbilical cords attached to their diving suits. These two-inch-thick clusters of tubes carried air, communications lines, power for the lamps and cameras on their helmets, and hot water to keep their suits warm—the seawater was just 39 degrees F. At the core was a steel-reinforced rope. Each diver had 165 feet of this lifeline coiled and ready inside the bell. Allcock’s job was to feed the line to the divers as needed.

Above water, the wind was about 35 mph and the seas some 13 feet high. Rough, but nothing the Topaz couldn’t handle. Instead of fixed propellers, the ship had five thrusters that could each be rotated. A dynamic positioning system kept the ship locked in place by constantly adjusting these, so there was no need for an anchor. The job was routine, Allcock told Lemons as he secured the heavy helmet for his partner. “There’s no rush. Take your time.” Lemons gave him the thumbs-up. He felt relaxed, focused, and ready to go.

Dropping through the two-and-a-half-foot hole at the bottom of the bell and into the dark ocean was always a magical moment for Lemons. Leaving behind the claustrophobic diving bell, he felt weightless, sediment and fleeting marine life caught in the light of his helmet lamp. He and Yuasa started work within the manifold, a structure 30 feet high and 66 feet long; its pipes and valves managed oil flowing from wells to platforms. Toiling a few feet apart with spanners and other tools, the pair would be underwater for six hours.

Up on the ship, dive supervisor Craig Frederick sat before a bank of controls and monitors showing the feeds from the divers’ helmet cameras. He followed their progress, giving instructions by intercom for each stage of the job. Meanwhile, in the cramped bell, Allcock sat surrounded by gauges. He monitored his colleagues’ oxygen and carbon dioxide levels but had no communication with them.

Lemons had been working for about an hour when he heard a noise from Frederick’s control room. An alarm. Perhaps the crew was running a test?

In fact, the Topaz had a major problem. The green light on Frederick’s instrument panel was suddenly glowing amber, then red. I’ve never seen that before, Frederick thought, alarmed. The positioning system had failed. The boat was now drifting and would soon drag the divers with it.

“Leave your tools and get back to the bell,” Frederick ordered. It was a highly unusual request, and Lemons and Yuasa started climbing hand-over-hand up their umbilicals toward the top of the structure. In the bell, Allcock didn’t know what was happening but followed Frederick’s instruction to start hauling in the cords.

Glancing up, Lemons had expected to see the bell’s lights, but there was only blackness. Then he felt his umbilical tugging as he reached the top of the manifold and saw that it had looped around a metal outcrop. He struggled to unhitch it, but the knot only pulled tighter. What’s going on? he thought.

In the bell, Allcock saw that Lemons’s line was suddenly taut. Frederick ordered, “Give Diver 2 more slack.”

“I can’t!” Allcock replied. Not only was it too tight, the cord was pulling its anchor off the wall, steel struts bending, bolts groaning. It was unthinkable: If the cord broke off, it would leave Lemons adrift and without oxygen. Allcock also knew that in this tiny space, if it came loose, it would knock him through the bottom of the bell into the water. He quickly climbed onto his seat to get out of the way. But there was nothing he could do for Lemons.

As Lemons struggled to free himself, Yuasa tried to get back to help, flailing his arms against the water. He almost made it. The two divers’ hands were just a couple of yards apart when Yuasa’s cord yanked him away. Lemons saw a look of apology on Yuasa’s face as he disappeared into the dark.

Lemons redoubled his frantic attempts to dislodge the cord. He heard it creak ominously, and then the air-supply line broke, followed by the communications feed. Unable to inhale, Lemons instinctively opened the emergency air tank on his back, as he’d done many times in training. Seconds later, there was a noise like a shotgun as the cable snapped. His lifeline had severed completely.

Lemons was thrown backward, sinking slowly, his helmet silent without the intercom, his lights dead, his suit beginning to cool. He knew he had about eight minutes of oxygen.

In the bell, Allcock feverishly pulled up the slack umbilical, hoping Lemons would be at the end of it. His heart sank as the broken hot-water hose came up. Then came the hissing air line. He felt sick. “I’ve lost my diver!” he shouted to Frederick.

Landing on the soft seabed, Lemons struggled to his feet in total darkness. The ship could track him via a beacon on his suit, but he knew that if he could somehow get himself to the top of the manifold, there was a better chance of rescue before his oxygen ran out. Yet he had no idea where it was. What if he walked the wrong way into the blackness?

He picked a direction almost at random and took cautious steps, feeling only the mud beneath his feet. Suddenly his outstretched hands struck metal. He grasped it in relief and then began struggling up the structure, breathing hard.

Reaching the top, he still couldn’t see the bell. Not a speck of light. Where had the Topaz gone? He crawled onto the platform and clung to the metal grille, terrified the current would drag him away. He reckoned he had about five minutes of air left. He knew his chances of surviving this were slim.

Yet the situation was even worse than he realized. The ship was now some 700 feet away. The crew was desperately trying to steer back, but without the positioning system, it took two people to manually coordinate the thrusters. The Topaz was slowly zigzagging against the waves.

The minutes passed, and Lemons’s fear turned to grief. This is probably where I die. He’d never see their house finished, never have children. “I’m sorry, Morag!” he called out. His mind fumbled with mundane practicalities. Does she know when the next payment for the building work is due?

He shouted out for Allcock. “Where are you?”

His chest grew tighter as his oxygen dwindled. I hope dying doesn’t hurt, he thought. He felt himself slowly slipping into unconsciousness.

Frederick had ordered the Topaz’s remotely operated underwater vehicle to go down and look for Lemons. It sent back pictures of him lying on the metal grille. His hands seemed to be twitching. Was he was still alive, or were his limbs just moving in the current? It was 16 minutes since the umbilical had snapped.

By now, Yuasa had made it back to the bell, poised to retrieve Lemons if they could get back in position. Frederick kept him and Allcock updated on the boat’s progress, though he massaged the truth to keep their spirits up. “We’re nearly there.”

Yuasa assumed he’d be recovering a body. Allcock’s thoughts were darkening, too, and he wondered how he’d tell Martin that her fiancé wasn’t coming home. The wait was agonizing, but he tried to keep hope alive. We’ve not forgotten you, lad, he said silently. Hang in there.

Attempts by the Topaz’s engineers to reengage the positioning system had been futile, so in desperation they shut it down and restarted it. Amazingly, this worked.

More than 25 minutes had passed since Lemons’s umbilical snapped.

Finally, with the ship over the dive site, Yuasa dropped down and found Lemons on his back. He glanced through Lemons’s mask; ominously, there was water inside. He clipped Lemons onto a rescue lanyard and began hauling them both up his umbilical cord. Lemons was a big man; it was like trying to carry a giant starfish. By the time he was able to push Lemons’s upper body into the bell, another six minutes had passed.

Allcock unclipped Lemons’s helmet. His eyes were closed, his bald head as blue as a pair of jeans. Allcock knew there was little chance of surviving that long without oxygen, but with nothing to lose, he kept talking. “You’ve had an accident. I’m going to give you CPR.”

He gave Lemons two breaths. And unbelievably, Lemons suddenly inhaled. His eyes opened. He blinked.

Allcock could have danced a jig. He’s back with us! For Frederick, watching via monitor, it was a big moment. “Are you all right?” he asked on the intercom. Lemons gave a weak thumbs-up.

Allcock probed him with questions after flushing his suit with hot water.

“Do you know where you are?”

“Yeah.”

“You know you’ve had a broken umbilical?”

“Yeah.”

Lemons was groggy but, remarkably, seemed himself. Back in the ship’s SAT chamber, he got medical attention while Yuasa and Allcock had, as Allcock remembers, “a bit of a hug.” Once Lemons was stable, they visited him. There were more hugs.

Over the next three days, as the men depressurized on the Topaz, now docked at Aberdeen, they talked through what had happened over and over. It helped them deal with the shock. All gently teased Lemons about the CPR, saying that “snogging,” or making out, isn’t usually done on a dive.

How Lemons survived, and without brain damage, remains unclear. The oxygen in divers’ gas is about four times richer than normal air, so his body may have been saturated with enough to keep him going. Hypothermia could have put him in shut-down mode, too, sending oxygen to his organs.

When Lemons phoned Martin, she was horrified to hear about her fiancé’s near miss and raced across Scotland to meet him as he disembarked from the Topaz. They kissed and hugged for a long time. For a distraction, they went to the movies, but Martin barely saw the film through her tears.

Three weeks later, once Lemons was declared fit, he returned to the North Sea with Yuasa and Allcock to finish the job. “I didn’t want to lose my nerve,” says Lemons, who is still a SAT diver.

“I’m proud of him,” adds Allcock. “Many would have said, ‘This is too dangerous. I’m not coming back.’ ”

The following April, Lemons and Martin got married in an emotional ceremony near their home. Yuasa couldn’t be there, but, says Lemons, “at the reception, people were buying Allcock whiskeys all night. And they were telling me, ‘I don’t even want to speak to you, I just want to hug you.’ ”

“A band played until 4 a.m. and the place was jumping,” recalls Martin. “People knew it was the wedding that almost never was.”

Lemons and Martin have since adopted a little girl, Eubh. They finished their house. But their life plans have accelerated. “We’re selling the house and moving to France already,” says Martin, smiling.

“I’ve had a glimpse of dying and I’m not scared,” says Lemons. “I know I’m lucky to have a second chance. I always had a lust for life, and the accident only made that stronger.”