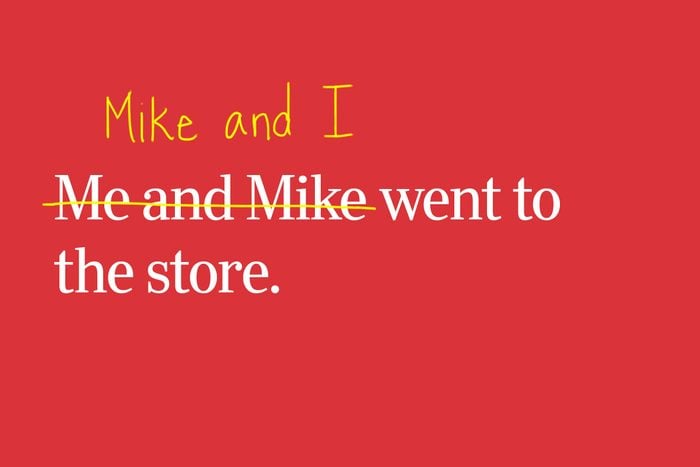

“Me” vs. “I”

This is one rule you probably heard starting back in elementary school. If you uttered, “Me and Mike went to the store,” you probably heard someone admonish, “Mike and I!” The problem with that, though, is that many people end up over-correcting. Though “Mike and I went to the store” is right, in some sentences, it is correct to use “me”—it depends on whether the first-person pronoun is a subject or an object. Here’s an easy way to know: Take out the other person, and see if “me” or “I” makes sense. “Me went to the store” is incorrect, but “My mom met me at the store” is perfectly fine. So it’s grammatically correct to say “My mom met me and my dad at the store,” not “my dad and I.”

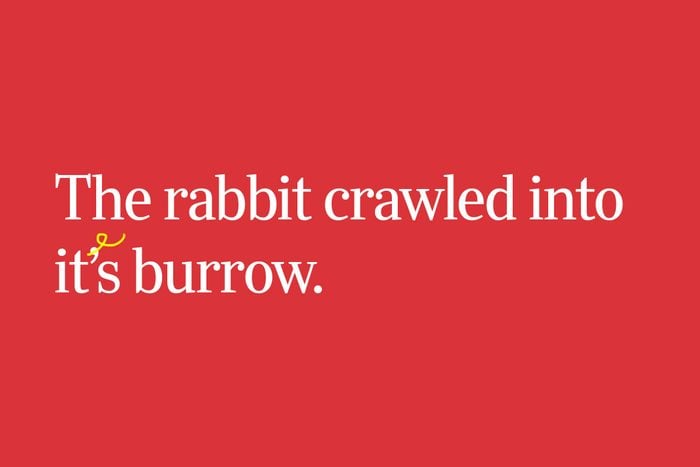

“It’s” vs. “its”

Use the wrong form of “its,” “there,” or “your,” and you’re (a contraction of “you are”) sure to have the grammar police wag their (the possessive form of “they”) fingers at you. But we do have to admit, when it comes to “it’s” vs. “its,” the confusion is easy to understand. In virtually every other situation, an apostrophe indicates possession. Bob’s car. Lisa’s house. Reader’s Digest. But when it comes to “it,” the possessive form is the form without the apostrophe. “The rabbit crawled into its burrow” is the correct use. In the case of “it’s,” the apostrophe means the word is a contraction of “it is.” It serves the same function as the apostrophe in “won’t” or “shouldn’t.” Find out some grammar myths your English teacher lied to you about.

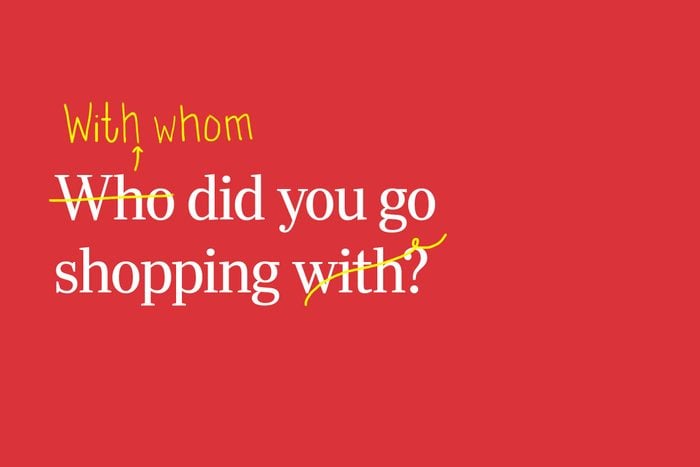

Who vs. whom

Boiled down, this rule is simple. “Who” refers to the subject of a sentence or clause, while “whom” refers to the object. But when you actually get down to using the two words in a sentence, that’s when things get dicey. You would ask, “Who went shopping with you?” since “Who” is the subject. But you could also ask, “With whom did you go shopping?” since “You” is the subject. Grammarly recommends a tip that should help you figure it out, if you’re truly determined to. Substitute the “who/whom” pronoun with “he/him” or “she/her,” rearranging the sentence if necessary. “She went shopping with you” (“who”), but “You went shopping with her” (“whom”).

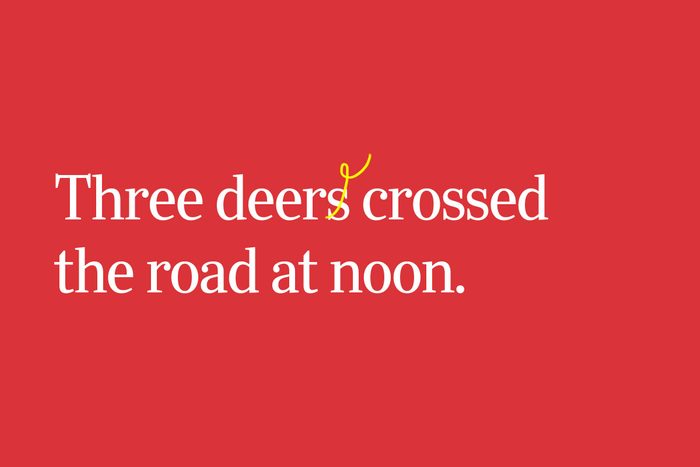

Wacky plurals

From “goose/geese” to “mouse/mice” to “foot/feet,” English is full of plural forms that leave even native speakers scratching their heads. And for some words, the plural form of the word is exactly the same as the singular form. Consider “deer,” “sheep,” and even “aircraft.” In the case of “aircraft,” it may be because the word “craft,” as in a vessel, originated as an “elliptical expression.” This means that it used to be a longer phrase and the scythes of time removed some words. The Oxford English Dictionary suggests that the old expression may have been something like “vessels of small craft.” “Deer,” though confusing, is pretty tame compared to these hilarious irregular plurals you won’t believe are real.

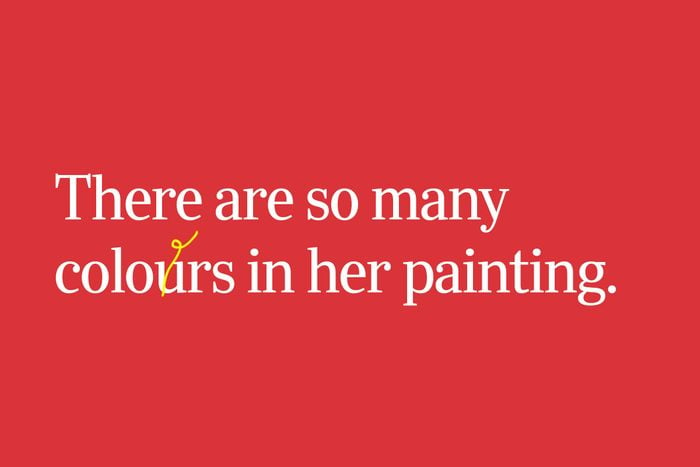

British vs. American spellings

Even within the single language of English, we’re not guaranteed standardized spelling. Or, rather, “standardised,” as people on the other side of the pond usually spell it! The fact that there are British and American spellings of different words is a bane of linguists and study-abroaders in English-speaking countries. For the different spellings, we can thank those pesky American revolutionaries. In 1789, Noah Webster of Webster’s Dictionary fame spearheaded the push toward “American” variations on some words. For the most part, the alterations of the words involved removing “superfluous” letters like the U in “colour” and the final “-me” in “programme.” Learn more about why Brits and Americans spell words like “color” differently.

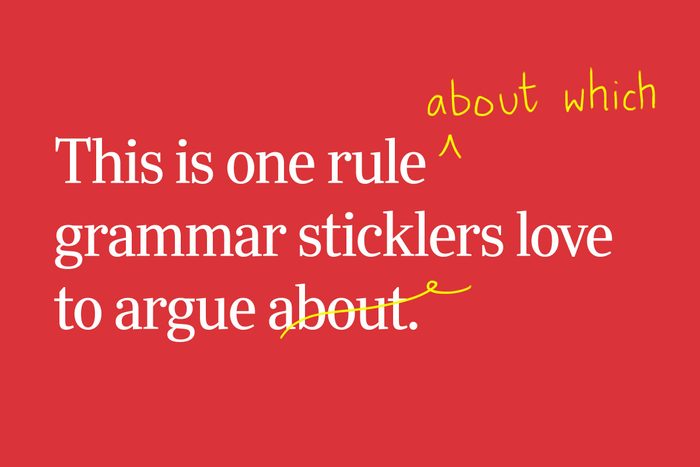

Ending sentences with prepositions

This is one rule that grammar sticklers love to argue about. (See what we did there?) Because the word “preposition” derives from a Latin word meaning “to place before,” some insist that prepositions should always go before their prepositional objects. However, while that’s true in Latin grammar, dictionary.com claims that “English grammar is different from Latin grammar, and the rule does not fit English.” The sentence, “This is one rule about which grammar sticklers love to argue,” just doesn’t flow the way “…love to argue about” does. And yet, the debate rages on. Here are some more grammar rules it’s probably safe to ignore.

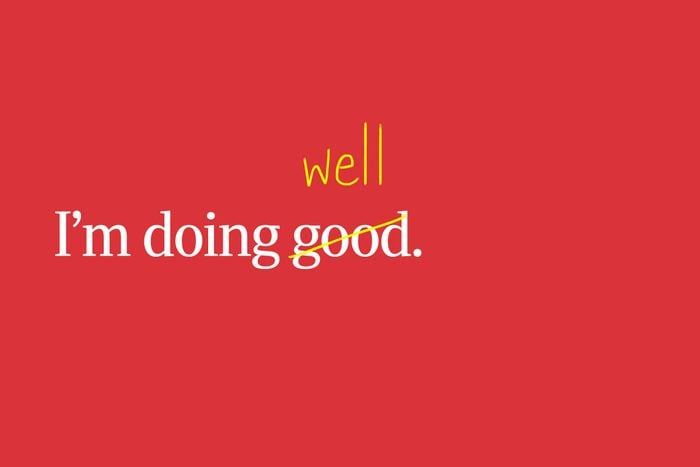

“Good” or “well”?

The big quandary with this one is that “good” is primarily an adjective (though it could be a noun), and “well” is an adverb. When people say, “I’m doing good,” they’re using “good” as an adverb to modify the verb “doing.” Technically, “I’m doing well” is the correct phrase, and “I’m doing good” actually means that you’re doing good deeds like a superhero. But, if you’re not hung up on being correct, it’s not worth it to stress about it—people will almost definitely know what you mean! There’s nothing “funner” than this debate on grammar!

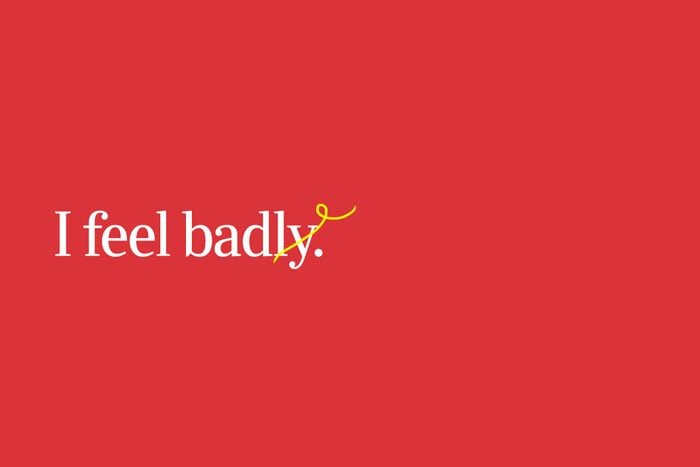

“Badly” or “bad”?

Less hotly debated than “good” vs. “well,” but equally confusing, is its moral counterpart: bad. Whether you “feel bad” about something as in feeling sorry or remorseful, or “feel bad” as in feeling sick or unpleasant, it should be “bad,” not “badly.” The confusing part about this, though, is that “badly” is also an adverb. But, simply because of the different usages of the verb “feel,” the only time “I feel badly” would be completely correct is if you were using “feel” to mean physically discern something by touch. If your hand is numb because you slept on your arm weird, you might feel badly. Here’s another rule, though, where context clues will almost definitely ensure that people know what you mean, regardless of whether you’re using the phrase correctly.

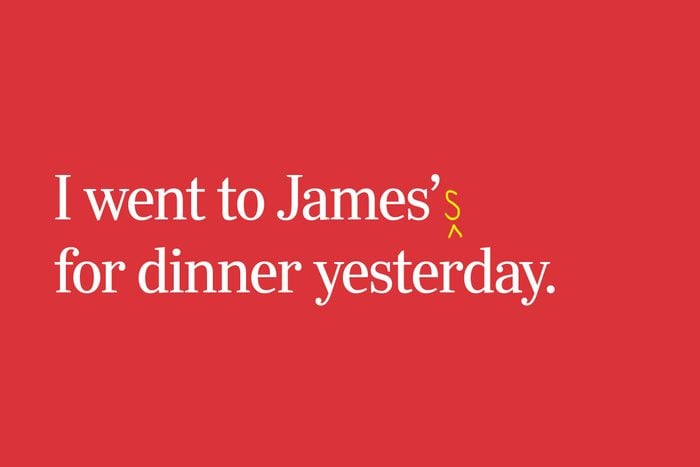

Apostrophes on words ending with S

Is “I went to Lucas’ for dinner” or “I went to Lucas’s for dinner” correct? Grammarians are divided, but the Oxford Living Dictionaries suggest this rule: Add an apostrophe and an S, as in the latter example, when you would actually pronounce the additional S while saying the sentence out loud. This extra S business gets even more confusing when the word ending with S is also plural. In that case, add an “-es” to the end and throw the apostrophe at the very end: “The Joneses’ car was blocking my driveway.” Here are more ways you’re still using apostrophes wrong.

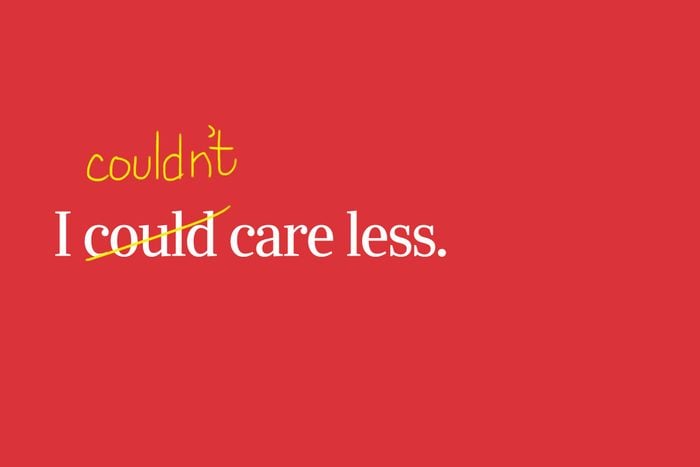

“Could care less”

“I couldn’t care less” means exactly that. You care so little that you could not care any less. Not so confusing! What is confusing about this one is the fact that people seem to think that “could care less” means the same thing, when it’s really the exact opposite. According to Grammar Girl, “The phrase ‘I couldn’t care less’ originated in Britain and made its way to the United States in the 1950s. The phrase ‘I could care less’ appeared in the U.S. about a decade later.” Harvard professor Stephen Pinker has suggested that people started saying “I could care less” sarcastically, meaning that they actually couldn’t care less, and that this version of the expression—without the intentional sarcasm—stuck.

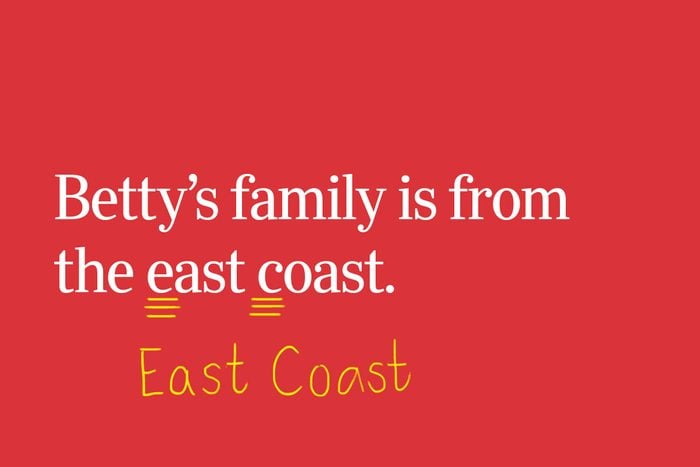

When to capitalize

You know to always capitalize proper nouns like names, but the lines get a little blurry with things like titles and locations. When you’re talking about the eastern United States, do you need to capitalize the E in “eastern”? You don’t, because you’re using “eastern” as an adjective. However, in the case of “the East Coast,” you should capitalize the E because the word “east” is part of the noun phrase. Yup, it’s enough to smoke your head for sure! The rules are pretty nuanced when it comes to different types of words. To see if you’re doing it right, check out this list of words you never knew needed to be capitalized.

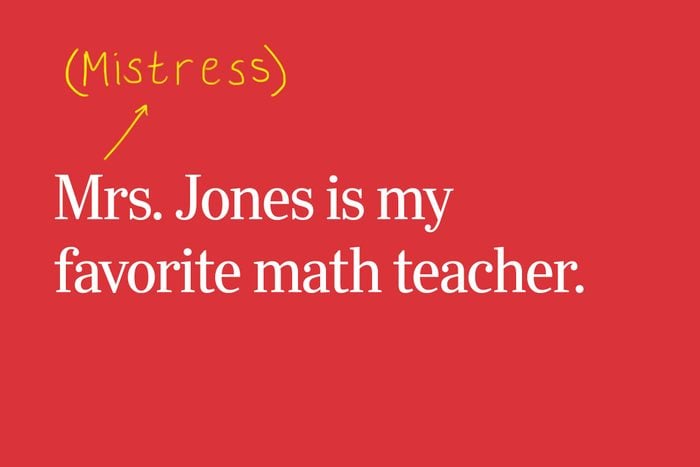

Abbreviations with seemingly random letters

The English language is rife with abbreviations that just don’t seem to make sense. Why does the abbreviation for “number” have an “O,” for instance? And where did wordsmiths get “lbs” from “pounds”? But in most cases, there is a linguistic explanation, usually having to do with an earlier spelling or meaning of the word. For instance, in the case of “Mrs.” and its seemingly random “R,” that abbreviation used to be short for the word “mistress,” as in the feminine equivalent of “master,” not “missus.” Over time, the connotations of “mistress” changed, but the spelling of “Mrs.” didn’t. By the way, here’s the difference between acronyms, abbreviations, and initialisms.

“E.g” vs. “i.e.”

Speaking of abbreviations, what the heck are these two short for, and why are they so similar? Well, wonder no more. “E.g.” is short for the Latin expression exempli gratia, which means “for example.” So “e.g.” is the expression you should use before providing an example or examples: “I like all of the common Thanksgiving foods, e.g., stuffing, turkey, and cranberry sauce.” Many people use “i.e.” in this context, though, while “i.e.” means something completely different. “I.e.” stands for id est, or “that is.” Use “i.e.” when you’re trying to explain or clarify something you just said: “I’ll get back to you soon, i.e., before the end of the week.”

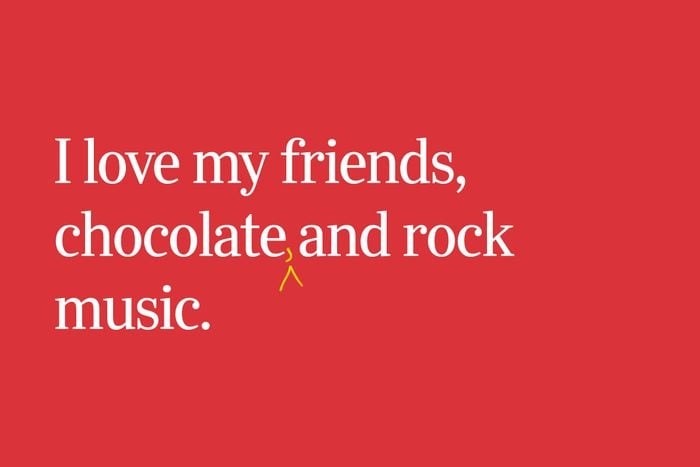

Oxford commas

Some style guides insist upon it; some don’t. A teeny comma has caused more than its share of debates in the grammar world. What it is, exactly, is the comma that goes before the last item in a sequence. Consider: “At the store, I bought apples, pears, bananas, and blueberries.” Does that comma after “bananas” need to be there or not? Sometimes it is necessary to preserve the meaning of the sentence, as in, “I love my friends, chocolate and rock music.” Chances are, chocolate and rock music are not the friends you were referring to, so a comma after “chocolate” is a grammatical must. But, in the fruit example, it doesn’t change the meaning, so some grammarians argue that the “and” serves the same function as the Oxford comma, and the comma isn’t needed.

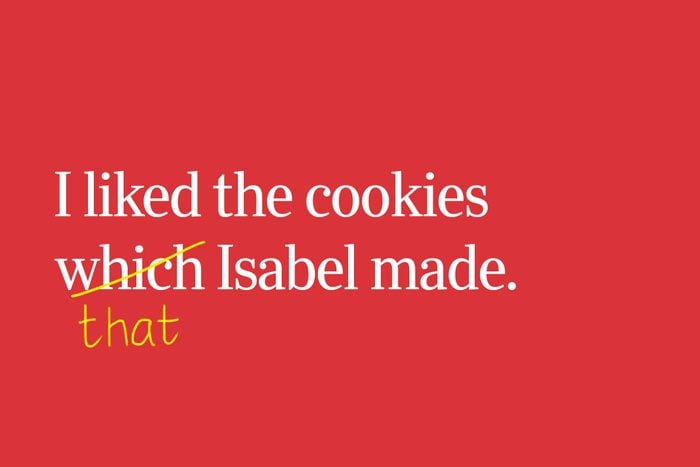

“Which” vs. “that”

“Which” and “that” are both relative pronouns, meaning that they begin an independent clause and connect it to a dependent clause. Essentially, they serve the same grammatical purpose, so people use them interchangeably. But…should they? According to the rules, “which” should only be used with a comma, while “that” should be reserved for comma-free clauses that are essential to the meaning of the sentence. Consider: “I liked the cookies that Isabel made better than the store-bought ones,” vs. “We ate the cookies, which Isabel made, in less than five minutes.” But, in truth, this is some deep-cut grammar pedantic-ness, and people don’t really tend to strictly adhere to it.

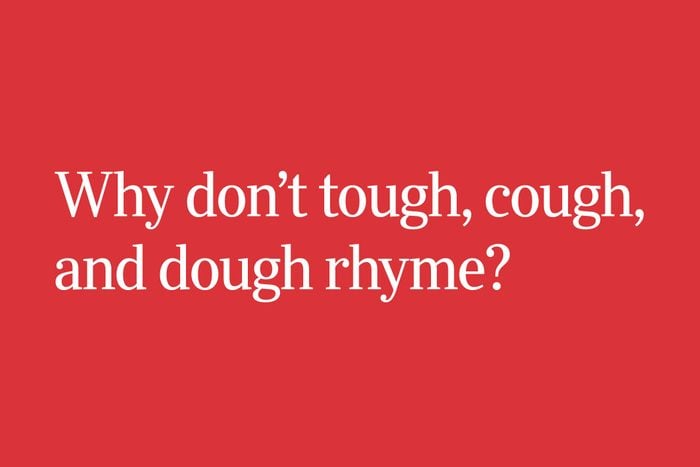

Perplexing pronunciations

Seriously, English—why don’t “though” and “through” rhyme?! Why is the O pronounced differently in “comb” and “bomb”? Or “plow” and “slow”? (This hilarious poem explores even more examples, in rhyme, no less!) The English alphabet only has 26 letters, but each of those letters may have up to seven different pronunciations. And don’t get us started on the words that you’re supposed to pronounce differently in different cases. For instance, you’re technically supposed to be pronouncing “the” like “thee” when the next word starts with a vowel sound. But if you don’t take that into account every time you say “the”—which is, after all, the most common word in English—we certainly won’t fault you for it! Here are 12 more grammatical errors even smart people make.

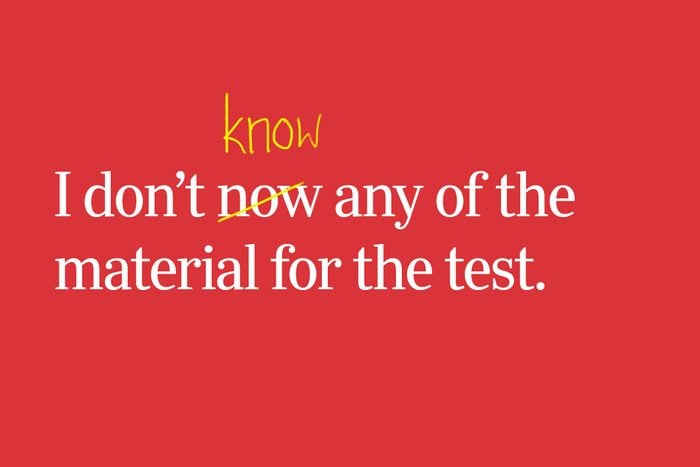

Silent letters

Adding confusion to the matter of letters with multiple pronunciations is the fact that sometimes, letters are there, but you don’t pronounce them at all! Why does “island” have an S? What is the purpose of the K in “know”? And why is there a G in “phlegm”? In many cases, the silent letters are present because the pronunciation of the words changed as the language evolved, while the spelling stayed the same. Other times, the disparity is because the words came from other languages, such as “tsunami” from Japanese and “rendezvous” from French.

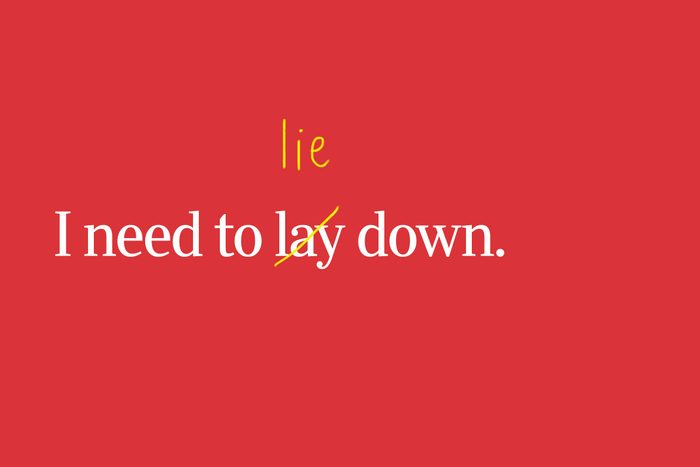

“Lay” or “lie”?

When it comes to commonly confused words (or phrases like “all of a sudden” and “all of the sudden”), there may not be a more understandably mixed-up pair than “lay” and “lie.” The words aren’t interchangeable, though many people use them that way. “Lay” needs an object, while “lie” doesn’t take an object. Technically, saying “I need to lay down” is incorrect, because you have to lay something down. “Please lay that expensive book down on the table carefully” is the correct use of “lay.” But the real confusion comes from the fact that the past tense of “lie” is… “lay”! “He wasn’t feeling well, so he lay down” is correct. The past tense of “lay,” meanwhile, is “laid.” It’s enough to make your head hurt so much that you might need to lie down, as are these other things you’ve probably been saying wrong.

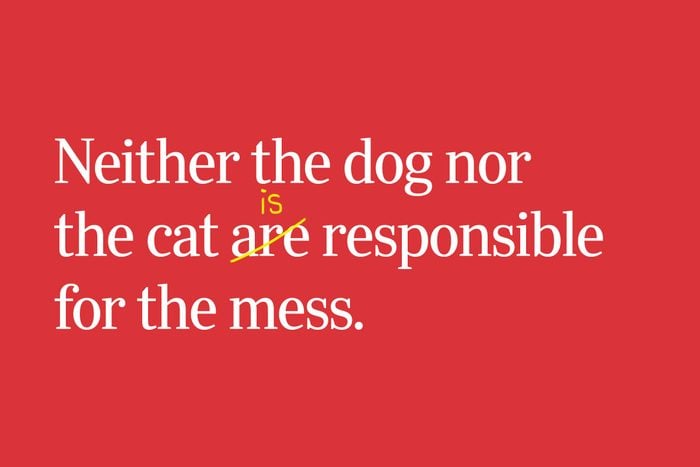

“Neither”—singular or plural?

When you say “neither,” you’re referring to more than one person or thing, so “neither” should take a plural verb form, right? Well…no. Both “neither” and “either” are always singular if the two things you’re talking about are singular: “Neither the dog [just one dog] nor the cat [just one cat] is responsible for the mess.” The same goes for “Neither of the pets is responsible”—even though “pets” is plural, “neither” still means “neither one.” The only time it works to pluralize the verb is if one or both of the subjects is plural: “Neither Lady Gaga nor the Backstreet Boys are performing tonight” is correct, since the closest subject to the verb, “the Backstreet Boys,” is plural. Phew!

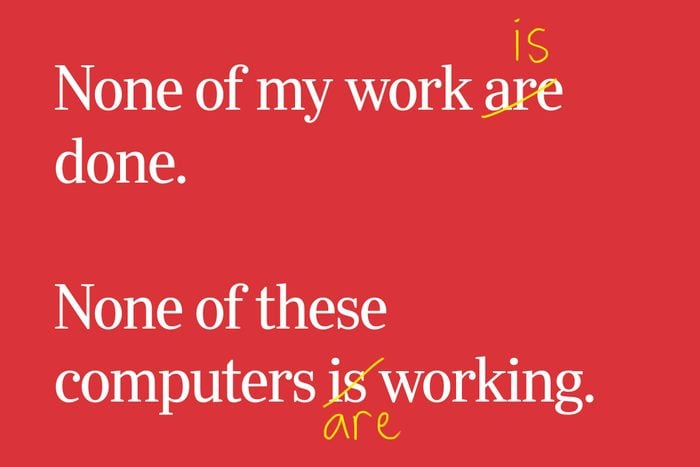

“None”—singular or plural?

If “neither” is singular, “none” should be too, right? Honestly, with this rule, even strict grammar nerds tend to throw up their hands and say, “Use your judgment.” Usually, if the subject of the sentence is an uncountable noun, a singular verb makes sense: “None of the beer is left.” But if the subject represents a concrete number of people or things, you can usually get away with using a plural verb—and it tends to just sound better, too, as in “None of my cousins are coming to dinner.” If your brain can handle it after all this info, read on for more little grammar rules you can follow to sound smarter.