The truth about fireflies

Starting with the insects: Fireflies are not flies but flying beetles with luminous tails, and glow-worms are closely related to them, being the larvae of four different kinds of luminescent beetles (but flightless ones). Watch out for these 70 words and phrases that you’re probably using all wrong.

Serious sea creatures

Misnomers abound in the ocean too: starfish aren’t fish at all; they’re echinoderms, boneless creatures with a hard outer shell, like sea urchins and sand dollars. And jellyfish aren’t fish either; they’re cnidarians—the perfect otherworldly name for these gelatinous alien forms with drifting tentacles. On the other hand, electric eels apparently really are fish—they’re close relatives of boring old varieties like carp and catfish. Here are 75 funny words you’ve probably never heard before.

Guinea pigs

We can’t possibly name all the misnamed animals further up the food chain. But here are a few favorites: Neither flying foxes nor flying squirrels fly; they hop and glide instead. Guinea pigs are neither pigs nor from Guinea; they’re rodents that originated in the Andes where they’re considered a delicacy (yep, they’re food in Peru). The cuddly koala bear, symbol of Australia is not only not a bear, it’s a marsupial. Mountain goats are actually antelopes. But sometimes scientists do change their minds about this stuff: until recently the giant panda was considered a relative of the raccoon, but now researchers have placed it back in the bear family. Here are 22 words and phrases originated in the military.

Faux chocolate

In the man-made category, white chocolate isn’t chocolate at all; it’s mainly flavored cocoa butter and cream. But head cheese has nothing to do with milk products; it’s made of chopped pork or beef scraps in an aspic jelly.

In the international food hall

Then there’s the question of where foods are from. French fries are probably from 17th century Belgium. Recipes for French toast is first recorded in the Middle Ages, well before there was a France, and the French themselves call it “pain perdu” or lost bread—probably because it’s a good way to use up those stale scraps which would otherwise be lost. Jerusalem artichokes are neither artichokes nor from Jerusalem. They proliferate everywhere from Canada to Florida, but nowhere near the Middle East. Some say the name is derived from “girasole,” or sunflower in Italian. German chocolate cake is reportedly from 19th century America, invented by a man with the last name German. And Danish pastries are actually Austrian in origin. Here are 41 little grammar rules you can follow to sound smarter.

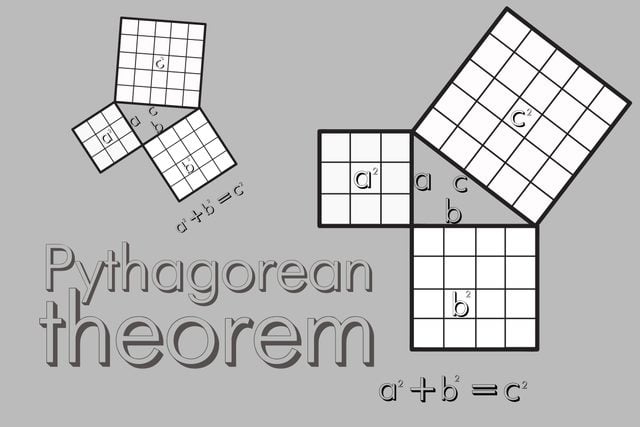

Giving credit where it’s not due

Pythagorus was by no means the first to come up with the theorem that allows us to solve for the sides of a right triangle: the Babylonians, ancient Egyptians, Chinese, and Indians all recorded their own versions of it hundreds of years before him. Chinese checkers are neither checkers nor from China; they were invented in Germany in the late 19th century. Authentic Panama hats are made in Ecuador but were first marketed and sold in Panama. And Arabic numerals were first used in India.

Hitting the right note

Musical misnomers form their own small special category: Both the French horn and the English horn are really variants of the German horn. The name Jews harp is a corruption of “jaws harp,” since the instrument is gripped between the teeth while being played. Violin strings are known as catgut but they’re really made from the intestines of sheep.

Nothing but the facts, ma’am

U.S. history is full of misnomers. Native Americans were called “Indians” because Columbus was seeking a new route to India when he landed in North America. The Battle of Bunker Hill, the first skirmish in the American Revolution, was mostly fought on nearby Breed’s Hill. The shootout at the O.K. Corral took place down the street in a vacant lot.

Islands in the stream

But America has no monopoly on misleading names. For example, London’s Isle of Dogs isn’t really an island; it’s a spit of land jutting out into the Thames and surrounded by water on three sides. The Canary Islands do have lots of canaries but they also once had a lot of wild dogs, so the name is actually a corruption of canis, meaning dog in Latin. Say these 9 words and we’ll be able to tell what part of the U.S. you grew up in.

A question of numbers

The Thousand Days’ War in Colombia was 1,130 days long. The Hundred Years’ War between England and France went on for 116 years. And there are 1,864 islands in the Thousand Islands archipelago along the U.S.-Canadian border. But the Thirty Years’ War in central Europe really did only last 30 years.

Close but no cigar

Finally, we just can’t leave out our favorite misnomer: however hard you may howl when you hit it, your funny bone is the ulnar nerve, not a bone. Next, check out the origins of these 14 commonly used phrases.