It’s Not Your Imagination, Air Turbulence Is Getting Worse—Here’s Why

Updated: Sep. 21, 2023

Flights are getting bumpier, and experts say they know what's to blame. Fasten your seatbelts—here's why air turbulence incidents are increasing.

We’re in for a bumpy ride. If you’ve noticed an increase in turbulence during air travel lately, you’re not wrong. A recent study has shown that turbulence—the kind that makes for a bumpy and potentially scary flight—is getting worse. The 2023 study from the American Geophysical Union analyzed clear-air turbulence (CAT) trends globally, finding increases at certain aircraft cruising altitudes. The study also projected CAT to intensify in response to future climate change—one more reason to keep your seat upright and stay buckled-in when flying.

We asked two aviation experts to explain the physics of air turbulence, why it’s getting worse and how dangerous it really is for commercial aircraft and its passengers.

Get Reader’s Digest’s Read Up newsletter for travel, humor, cleaning, tech and fun facts all week long.

What causes air turbulence?

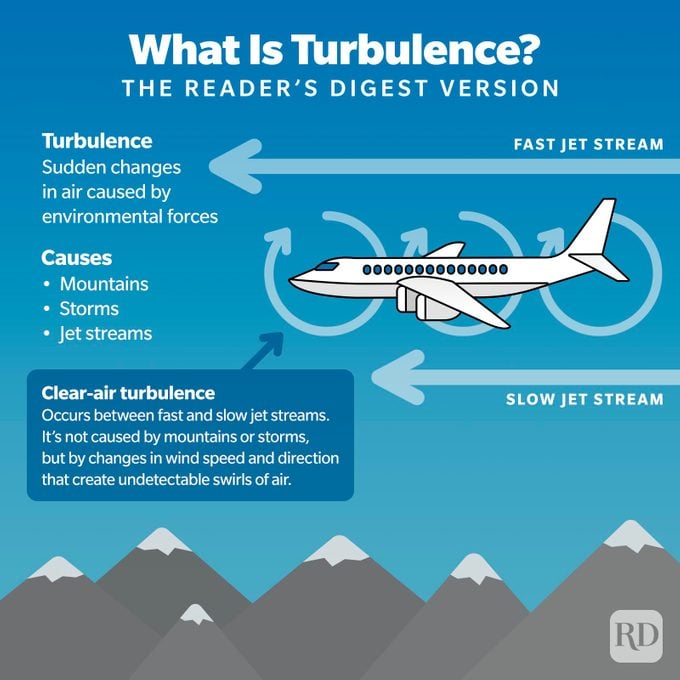

Air turbulence is a naturally occurring event caused by a number of environmental factors, says Dan Bubb, PhD, a former airline pilot, current associate professor at the University of Nevada, Las Vegas, and author of Landing in Las Vegas: Commercial Aviation and the Making of a Tourist City. According to Bubb, it’s a bit like juggling. “Turbulence occurs when you have unstable air,” he says. “If you imagine a juggler juggling balls, some balls will go higher than others. The higher a ball goes, the more unstable the parcel of air becomes, thereby generating turbulence.”

Factors such as thunderstorms, mountain waves and thermals, or rising air currents can cause turbulence. “However, when discussing commercial flights, we most generally think of clear-air turbulence,” says Thomas Guinn, PhD, a private pilot and professor and chair of the Applied Aviation Sciences Department at the College of Aviation at Embry-Riddle Aeronautical University.

What is clear-air turbulence?

Clear-air turbulence occurs in cloudless regions (away from storms) and is predominantly created by intense changes in wind direction and/or speed. “This occurs near the jet stream when the wind speeds change quickly with both horizontal and vertical distance,” says Guinn. “When the [wind] shear is strong enough, the air will overturn, creating turbulent whirls that cause the aircraft to experience rapid up-and-down motions. This is loosely similar to how strong winds over the ocean surface can create large crashing waves.”

Unlike turbulence caused by thunderstorms or clouds, CAT is not visible to pilots or meteorologists or even detectable by radar, which means it’s virtually impossible for pilots to avoid. Plus, CAT most often occurs above 18,000 feet—the cruising altitude area of most commercial aircraft.

Why is turbulence getting worse?

The study reanalyzed CAT satellite data collected between 1979 and 2020 and found a marked increase in CAT, especially moderate to severe CAT, or the kind that will rattle not just the plane, but your nerves as well. So what’s the reason behind the worsening of this type of turbulence? Climate change, says the study.

The steadily increasing amount of warm air due to carbon dioxide emissions has kept pace with the rate of CAT increases. That warm air rises into the jet stream, creating invisible wind shears that cause clear-air turbulence. “Climate change is having a significant impact on the frequency of air turbulence because of greater instances of highly unstable air,” says Bubb. “Part of this is due to times when the jet stream is stronger.” But it also occurs at the frontal boundary, where warm and cold fronts meet. As a result, he says, “areas along the frontal boundary can experience severe thunderstorms with considerable rain, winds and turbulence.”

Guinn adds that several studies have indicated turbulence may become more frequent and have greater intensity as climate change modifies both jet stream and thunderstorm patterns. According to one study that Guinn cites, by 2050 to 2080, “winter severe clear-air turbulence events will become as common as moderate turbulence events are currently,” he says.

So where are the most active areas of increased CAT? Over the busy North Atlantic Tracks flight corridor that connects Europe to North America, and across a large swath of the continental United States. (In some areas, there was a 100% increase in the incidence of moderate or greater clear-air turbulence.)

How dangerous is turbulence during a flight?

Despite the dire predictions, experts say that air turbulence, either caused by CAT or more visible storms and cloud formations, is not at all likely to bring down a commercial aircraft. “Turbulence can be extremely dangerous, causing passenger and crew injuries as well as aircraft damage, but it is unlikely to cause a commercial airline aircraft to crash,” says Guinn.

Bubb concurs. “Air turbulence can be severe, but not enough to bring down an airplane,” he says. “Commercial passenger planes are sturdily built and undergo numerous stress tests to ensure their airworthiness before they go into service.”

Injuries related to CAT and storm turbulence—most often head and neck injuries—occur when the jolt is strong enough to cause passengers to accelerate out of their seats. It’s why the safest airlines have flight safety protocols. The majority of passenger injuries can be prevented simply by keeping your seatbelt fastened at all times, even when it feels like smooth sailing.

“Since turbulence can occur at any time, it’s always best to leave your seatbelt on and minimize walking about the cabin,” says Guinn. “Certainly when the captain turns on the seatbelt sign for turbulence, passengers should take heed, since it indicates turbulence has been observed along the flight path by another pilot or is forecast to occur.”

About the experts

- Dan Bubb, PhD, is a former airline pilot and the current associate professor in residence at the University of Nevada, Las Vegas. He is the author of Landing in Las Vegas: Commercial Aviation and the Making of a Tourist City, and his research interests include U.S. and world history and commercial aviation and airport history.

- Thomas Guinn, PhD, is professor and chair of the Applied Aviation Sciences Department at the College of Aviation at Embry-Riddle Aeronautical University. A private pilot, his research areas include aviation meteorology, tropical cyclone dynamics and the pedagogy of teaching atmospheric science.

Sources:

- Advancing Earth and Space Sciences: “Evidence for Large Increases in Clear-Air Turbulence Over the Past Four Decades”

- Advancing Earth and Space Sciences: “Global Response of Clear-Air Turbulence to Climate Change”