How to Tell If Someone Is Lying, According to a Human Lie Detector

Updated: Jan. 25, 2024

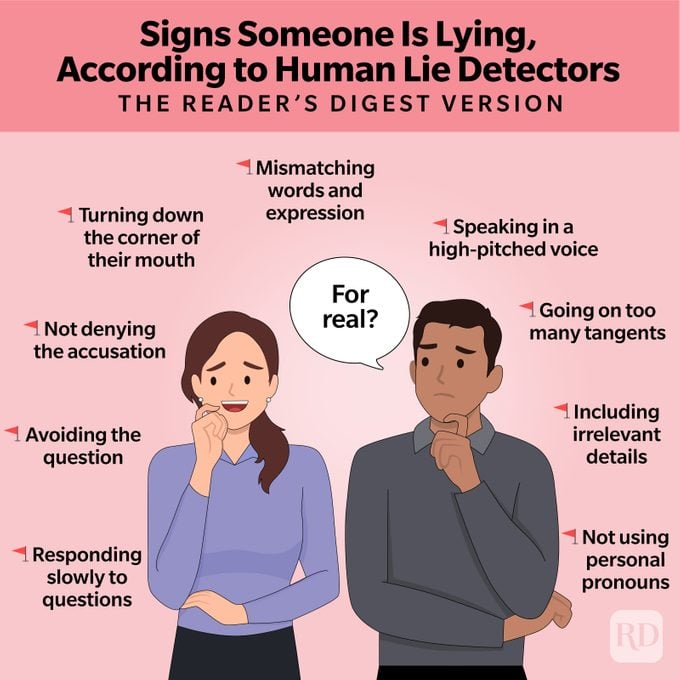

Body language, facial expressions and speaking habits can help you detect dishonesty. Here's how to tell if someone is lying, according to people who spot lies for a living.

Despite what shows like Poker Face and countless police procedurals would have you believe, people generally aren’t very good at telling when other people are lying. Research has debunked many of our long-held beliefs about what signals indicate deception. But there are evidence-based strategies for how to tell if someone is lying.

Facial expressions, mannerisms, actions, reactions and ways of speaking can all become potential red flags that someone is being deceptive. So how can you tell? “There’s no single sign on the face of deceit, but microexpressions—the brief, involuntary twitches our faces make in response to our emotions—can help you analyze someone’s emotions to clue you in to potential deception,” says Annie Särnblad, a facial expressions expert and author of Diary of a Human Lie Detector: Facial Expressions in Love, Lust and Lies.

Our use of language can also reveal whether we’re lying or being truthful. “While a single, casual word or phrase may not disclose much, a consistent linguistic pattern can be highly revealing, offering a kind of ‘linguistic fingerprint’ that divulges key aspects of our inner selves,” says David J. Lieberman, a psychotherapist, author of Mindreader and expert in human behavior who has conducted training for FBI profilers, the NSA, the CIA and the U.S. Department of Defense.

Whether you want to uncover dating profile lies, become more confident in your gut instinct about others or reveal con artist tricks to avoid being taken advantage of, these strategies from the experts can help you discover how to read people so you’ll never be lied to again.

Get Reader’s Digest’s Read Up newsletter for more knowledge, humor, cleaning, travel, tech and fun facts all week long.

How often do people lie?

Some decades-old research claims that people lie a lot: One oft-cited 2002 study found that 60% of 121 subjects lied in a 10-minute conversation when told to appear “likable” or “competent.” But newer findings paint a different picture: Most people don’t lie that much, but the ones who do lie a lot.

A 2021 study in the journal Communication Monographs examined 116,366 lies told by 632 participants over 91 consecutive days and found that 75% of respondents self-reported zero to two lies per day. The majority of the lies were told by a few prolific liars. In addition, almost 90% of all the lies fell into the category of a white lie, like saying you like a gift when you don’t.

A 2017 YouGov survey found similar results when it asked how often people lie, no matter how small the lie. The most common response (from 36% of respondents) was less than once a month; the second most common response (from 21% of respondents) was never.

Of course, both studies looked at self-reported fibs. The accuracy of the data depends on whether participants define a lie as an outright deception or just a slight spin on the truth—and if they’re being truthful with themselves.

Why is it so hard to tell if someone is lying?

We generally tend to think of body language mistakes as dead giveaways someone is bending the truth. Understanding how to tell when someone is lying is a matter of spotting crossed arms, an averted gaze and fidgeting … right? Not so! Reading body language is actually unreliable.

Even involuntary physiological responses that might show up on a polygraph, such as changes in heart rate or blood pressure, are untrustworthy. Think about it: A truthful person hooked up to a lie detector machine would be understandably nervous—perhaps even more so than an accomplished liar who can better control these responses.

But it’s equally hard to tell if someone is lying without a lie detector. Studies show that when it comes to our ability to detect lies, we’re easily duped, no matter how confident we are about our powers of perception. Making the task even trickier is the fact that liars may use a bit of reverse psychology, taking into account listeners’ expectations and changing their behavior to avoid detection.

Instead of body language or lie-detecting machines, Lieberman focuses on verbal indicators to reveal the habits of untrustworthy people. “Our choice of words and syntax can provide a window into our attitudes, values and behaviors—they can even serve as indicators of our emotional well-being, honesty or security within relationships,” he says.

Similarly, subconscious facial microexpressions offer a more reliable view of truthfulness. “When you’re trying to tell if someone is lying, microexpressions are more black-and-white than body language, simply because they precede the thought process,” Särnblad says. “In order to lie with your microexpressions, you must be able to fully convince your brain that you’re experiencing a different reality. Most people aren’t able to do this because it creates cognitive overload.”

How to tell if someone is lying

Although we should have trust in our relationships, sometimes doubt creeps in about our friends’, partners’ and even children’s sneaky behaviors. So how can you tell if someone is lying or telling the truth? To find out, we turned to the pros.

Our experts share ways to catch someone in a lie, including some tells used to spot lies in law-enforcement training. Although there are differences between everyday interactions and an interrogation room, you can still use these strategies to help figure out the most common lies. But be warned: One of these signs is probably not enough; you’ll need to look at the patterns of the potential liar’s behavior and identify more than one red flag.

Listen for oversell expressions

Research has shown that verbal cues are some of the most accurate indicators that someone is lying. These linguistic signs include overselling your point.

“Declarations of emphasis, called oversell expressions, often indicate active impression management,” Lieberman says, meaning that the liar is really, really trying to give the impression of innocence. “Consider the suspect who says that he is ‘100% not guilty’ or is ‘absolutely, completely positive that …’ People often inject such words with the intention to present an image of confidence, but if I asked whether you had ever robbed a bank, you would likely respond with ‘No’ and not, ‘I am certain I never robbed a bank’ or ‘I promise I never robbed a bank.'”

When asked a question, the most direct answer is often the most honest.

Look for a mismatch between words and expressions

If the words coming out of a person’s mouth don’t seem to match their expression, it could be a sign they’re lying. “You’re looking for a mismatch between someone’s facial expression and what they are saying,” Särnblad says.

Here’s an example of how to tell if someone is lying using this tactic: Let’s say you ask an employee to handle a last-minute project. If they respond, “That sounds great” while looking concerned, they may be lying. Perhaps they’re swamped with work but don’t want to refuse the boss.

Pay attention to irrelevant details

Research shows that truth-tellers include relevant, verifiable details in their statements. A liar, on the other hand, may try to distract you with a bunch of information you really don’t need to know. The key to catching a liar is learning how to focus on the extraneous details.

“Someone making a deceitful statement often focuses heavily on irrelevant details to mimic the natural depth and richness found in a truthful statement,” Lieberman says. “He peppers the conversation with irrelevant details to distract you from the truth, as if he’s throwing sand in your face. This person knows that if his statement is too vague or too generic, you might not view it as trustworthy.”

These irrelevant details aren’t necessarily fake, though. In fact, they’re often true—one of the strategies self-reported good liars use to keep their stories simple and easy to remember.

“[The liar] also knows that the more complex the lie, the harder it is to maintain,” Lieberman says. “He tends to, then, emphasize truthful irrelevant information in an attempt to duplicate the layers of truth while simultaneously protecting himself from fabricating too many details that might come back to bite him later.”

Notice when the corner of the mouth turns down

Understanding how to tell if someone is lying goes beyond the words they say to the minute, subconscious reactions they have. To ferret out liars, pay attention to these microexpressions. “They are universal and hardwired in us humans, and present on our faces regardless of age, gender, socialization, culture or geographic location,” says Särnblad, who has a background in anthropology.

One of these is what she calls the “Oh crap!” microexpression. “It shows on the face in a pull of one corner of the mouth diagonally down toward the respective shoulder,” she says. “If someone shows the ‘Oh crap!’ expression when you ask if they’re able to do something, that may indicate a problem or a lie.”

This is both a clue that you’re being lied to and a warning for the next time you want to stretch the truth. Considering your face can betray your feelings, you may want to opt for honesty. At the very least, commit to always telling the truth in these instances.

Listen for tangents

Self-reported good liars say they embed their lies into truthful information. One way to tell if someone is lying, then, is to listen for tangential details in an otherwise truthful story.

“Unsolicited details [in truths]—those that the person brings up without prompting or asking—should be concise and in context, meaning they are immediately relevant to the point and not a tangential freight train,” Lieberman says. “For example, stating that the mugger ‘reeked of cologne’ is fine. An unnecessary extension becomes problematic and dubious: ‘He reeked of cologne. It was like the cheap stuff that probably sells for $5 a bottle. I don’t know how people can wear that stuff.’ True? Perhaps. Relevant? No.”

Note slow responses

Research has found that liars often take their time when responding to questions. “Speed indicates that a person doesn’t need time to think about their answer,” Särnblad says. “While simply pausing before responding doesn’t necessarily mean a lie will follow, it does mean the person pausing is considering their answer.”

Of course, there are many reasons for a measured response that don’t include lying. “For example, I find myself taking extra time to formulate my words when talking about something particularly sensitive or complicated,” she says. That’s a sign of emotional intelligence, not lying.

That said, if the pause is in response to something that should be straightforward, take heed.

Listen for conversational spotlights

Liars tend to highlight their messages with certain cues in their language that Lieberman calls conversational spotlights.

“What do words and phrases such as believe it or not, actually, as a matter of fact, basically, as it turns out, honestly and essentially have in common? These expressions often serve as linguistic markers that may indicate a speaker’s need to clarify, emphasize or substantiate what is being said,” he says. “They could be seen as the verbal equivalent of underlining or highlighting text, signaling to the listener that what follows is of particular importance or may be counter to what is generally assumed.”

Phrases like these are used to draw attention to and magnify the significance of the message, and by paying attention to them, you can better understand how to tell if someone is lying in specific situations.

“Remarkably, they indicate two entirely different things based on the context of the interaction,” Lieberman says. “When used by someone who is trying to sway another—a guilty suspect being interrogated—their use may indicate deception. However, when used non-sarcastically in a casual conversation, they mean that the person is open and interested in the conversation and is trying to engage and perhaps impress.”

So in everyday life, it might be a bit harder to spot a liar using this technique. “Let’s pepper our coffee shop exchange with a few of these conversational spotlights and note how they suggest a budding connection,” Lieberman says. But in a more serious conversation—such as if you suspect your significant other is cheating—these phrases take on a new meaning. Women and men tell plenty of lies, and in the right context, conversational spotlights can point a finger at potential untruths.

Check their comfort level

Fidgeting. Sweating. Eyes darting around with unease. This is the stereotype of someone who’s guilty in a crime show—yet in some cases, it’s actually true.

“Potential indications of lying can manifest as feeling nervous and uncomfortable,” Särnblad says. “With lie detection, we are specifically looking for when it doesn’t make sense for someone to be nervous if they are telling the truth, but their body language gives away their discomfort.”

For example, it makes sense for someone to be nervous in a police interrogation room, even if they’re telling the truth. But it might not make sense for a friend to be nervous when you’re having a conversation over brunch. On the other hand, experienced liars (one sign of a psychopath, by the way) might be able to correct for their nervousness, so this may be a tell only in someone who doesn’t often lie.

Listen to the pitch of their voice

If you think a friend is lying when their voice goes up an octave, you might be right. “What’s interesting is that higher voice inflection is just about the only reliable indicator of deception when it comes to the voice itself,” says Lieberman. “When a person lies, their voice does tend to go a little higher.”

As muscles of the vocal cords tense up, such as during stress from telling a lie, the vocal pitch rises. A 2021 study in the journal Nature Communications showed that even in different languages, a signature vocal pattern, including rising intonation and variable pitch, can be a way to tell if someone is lying.

Look out for personal pronouns

If someone doesn’t refer to themselves with the personal pronouns I, me or my, they may be lying. “From a psycholinguistic standpoint, pronouns can reveal whether someone is trying to distance or altogether separate himself from his words,” Lieberman says. “In much the same way that an unsophisticated liar might look away from you because eye contact increases intimacy and a person who is lying often feels a degree of guilt, a person making an untrue statement often seeks to subconsciously distance himself from his own words.”

Using personal pronouns means the person is confident about a statement; omitting them may signal someone’s reluctance to accept ownership of their words, as a liar might do.

Lieberman gives an example from everyday life: “A woman who believes what she’s saying is more likely to use a personal pronoun. For instance, ‘I really liked your presentation’ or ‘I loved what you said in the meeting,'” he says. “However, a person offering insincere flattery might choose to say, ‘Nice presentation’ or ‘Looks like you did a lot of research.'”

Law enforcement officers, he says, can recognize when people are filing a false report about their car being stolen because they often refer to it as “the car” or “that car” and not “my car.”

Just remember to be smart about the conclusions you draw—this is only one of many red flags, after all. “Of course, you can’t gauge a person’s honesty by a single sentence, but it’s the first clue,” he says.

Pay attention to word choice

When trying to tell the truth from a tall tale, you need to focus on more than the signs of lying. Be sure to zero in on the signs of truth-telling too.

Here’s an interesting fact: A truth-teller might use words that indicate closeness, such as here instead of there or this instead of those. Such words “show where a person or an object is in relation to the speaker,” Lieberman says. “These words also illuminate both physical distance and emotional distance. Oftentimes we use spatial immediacy to refer to someone or something that we feel positive toward and want to be associated with—’This is an interesting idea’ or “Here is an interesting idea.'”

But the converse isn’t true. “A colleague who says, ‘That’s an interesting idea’ is not necessarily feigning enthusiasm,” he says. “Language that reflects closeness and connection is correlated with one’s feelings, but a parallel should not be assumed with distancing language.”

Look for a mismatch between words and body language

Just as you need to pay close attention to whether someone’s expression and words mesh, you need to focus on whether their body language—namely, whether they’re touching or rubbing their body—and words align as well. If the two don’t match, you may be on the receiving end of a lie.

“We often touch, pull or rub our skin as we’re trying to comfort ourselves and self-soothe,” Särnblad says. “As an example, if we’re talking about how confident we are and at the same time cover our neck with one hand, the actions and words aren’t aligned. The body language defies our words and is a potential indicator of deception.”

But just because someone is fidgeting doesn’t mean they’re lying. If they have a reason to be nervous (for example, being questioned by police), these self-soothing gestures may be present even when they’re telling the truth.

Note whether they’re avoiding the question

If you’re telling the truth, your response tends to be brief and to the point. “A rule of thumb is that a truthful response is short and direct, not convoluted, long-winded or complicated. A reliable denial is direct and clear—for example, ‘No, I didn’t do it,'” Lieberman says. “People falsely accused, who are providing true statements, have no reason to hold back from strong, clear denials.”

But how do liars react when you’re asking them questions or otherwise confronting them? “A strong indication of deception is when someone doesn’t deny the allegations against him—or when he buries a ‘no’ under two pages of musings or a 10-minute diatribe,” Lieberman says. “If the denial consists of statements like, ‘How could you even ask me such a thing?’ or ‘This is crazy!’ or ‘Ask anyone who knows me—I would never do that!’ or ‘How could you question my honesty?’ then that raises suspicions, because none of these responses consists of a direct, straightforward denial.”

Think you’re dealing with a fibber? Although liars aim to distance themselves from guilt, they often have difficulty with using direct, clear language in their denial.

Lieberman offers a few examples of statements that claim innocence while avoiding the “did you do it?” question: “If someone didn’t kill his wife, then you don’t want to hear that he loved his wife and he would never do that, or that he’s not a monster or a crazy person,” he says. “If a teacher didn’t abuse his student, you don’t want to hear that he would never harm a child or that he’s not a pervert or that everyone in the school loves him. If your employee didn’t steal from your company or your nanny didn’t harm your child, you don’t want to hear from her that ‘everyone loves me, my reputation is spotless and I am not a bad person.'”

If such denials are included as part of a full response to an accusation after a direct denial, it’s OK. “But the centerpiece of the person’s response should be a consistent, clear denial of the act—and not proof that he is not the kind of person who could ever commit such an act,” he says.

Determine whether they directly denied the act

Look for distancing in a liar’s denial when confronted with something you think they did. “While we’re on the subject of denials, keep in mind that not all denials are created equal. A statement such as, ‘I deny these allegations,’ is not the same as ‘I didn’t do it,'” Lieberman says.

A denial of an allegation means that the person is refusing to acknowledge guilt, but this is not the same as denying that he committed the act. “A reliable denial is a clear ‘no’ and not phrases such as, ‘I deny the charges’ or ‘I would never have done this.'”

To sum up, he says, “only ‘no’ is a no, and for that matter, only ‘yes’ is a yes.”

About the experts

- David J. Lieberman, PhD, is a psychotherapist and expert in human behavior who has trained personnel in every branch of the U.S. military, the FBI, the CIA and the NSA. He is the author of 13 books, including Mindreader.

- Annie Särnblad is an expert in facial microexpressions and author of Diary of a Human Lie Detector. Certified in the Facial Action Coding System, she can numerically code the 10,000 muscle combinations in the human face. With a background in anthropology, she’s lived in nine countries while studying eight languages and is now a strategic advisor to business organizations.

Sources:

- Annual Review of Psychology: “Reading Lies: Nonverbal Communication and Deception”

- Basic and Applied Social Psychology: “Self-Presentation and Verbal Deception: Do Self-Presenters Lie More?”

- Communication Monographs: “Unpacking variation in lie prevalence: Prolific liars, bad lie days, or both?”

- YouGov.com: “Is it normal to lie to your significant other? 49% of Americans have more than once”

- Brain Sciences: “Verbal Lie Detection: Its Past, Present and Future”

- Frontiers in Psychiatry: “Accuracy, Confidence and Experiential Criteria for Lie Detection Through a Videotaped Interview”

- Journal of Cognition: “Cues to Lying May be Deceptive: Speaker and Listener Behaviour in an Interactive Game of Deception”

- Applied Cognitive Psychology: “Detecting smugglers: Identifying strategies and behaviours in individuals in possession of illicit objects”

- Psychiatry, Psychology and Law: “How researchers can make verbal lie detection more attractive for practitioners”

- Frontiers in Psychology: “Microexpressions Differentiate Truths from Lies About Future Malicious Intent”

- Journal of Applied Research in Memory and Cognition: “The Verifiability Approach: A Meta-Analysis”

- PLOS One: “Lie prevalence, lie characteristics and strategies of self-reported good liars”

- Psychological Bulletin: “Lying takes time: A meta-analysis on reaction time measures of deception”

- Nature Communications: “Listeners’ perceptions of the certainty and honesty of a speaker are associated with a common prosodic signature”