What Is IQ, and How Well Does It Predict Success?

Updated: Jan. 25, 2024

What does IQ measure? According to our experts, having formal intelligence and being smart are not necessarily the same thing.

Albert Einstein and Stephen Hawking are perhaps two of the most celebrated geniuses in modern history. And although there’s no evidence that either man ever took an IQ test, it’s estimated that both would have scored around 160. While that’s an impressive score, it’s not even close to being the highest IQ in the world, and that raises several questions: What is IQ? If you’re working on how to be smarter, what does your IQ score mean—and does it even matter? Can it predict whether you’ll lead an ordinary life or make trailblazing contributions to society?

While you can improve your cognitive ability with brain-boosting methods, such as finding new hobbies, learning something new or mastering a new language, your IQ tends to be stable. We spoke with experts to better understand the meaning of IQ and its implications. Here’s what they had to say.

Get Reader’s Digest’s Read Up newsletter for knowledge, humor, cleaning, travel, tech and fun facts all week long.

What is IQ?

IQ stands for intelligence quotient. It’s a score that results from taking one of several standardized tests that measures specific cognitive abilities.

When IQ tests were first developed in 1912, the score was meant to reflect the ratio (or quotient) of a person’s “mental age” divided by their chronological age and then multiplied by 100, according to Mensa International, a society of people who score in the top 2% of IQ tests. (Here’s a practice Mensa IQ test to see if you might qualify.) By that standard, a person whose chronological age was 10 and who also tested at a mental age of 10 would have an intelligence quotient of 100.

Today, after testing very large numbers of people for more than a century, that same score of 100 has come to be considered average.

How is IQ determined?

“Intelligence tests look at various cognitive abilities to determine overall mental or reasoning abilities,” says Renee Lexow, PsyD, supervisory psychologist at American Mensa, who acknowledges that there are different types of intelligence. “Intelligence tests seek to determine fluid intelligence (one’s ability to take new or novel information and think abstractly) and crystallized intelligence (knowledge already obtained and retained). Simply put, intelligence tests measure one’s ability to think, apply skills and problem solve.”

Numerous IQ tests are available; some of the most widely used are:

- Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale (WAIS IV)

- Wechsler Intelligence Scale for Children (WISC)

- Woodcock-Johnson Tests of Cognitive Abilities

- Stanford-Binet Intelligence Scales

- Raven’s Progressive Matrices

IQ tests use a range of formats; some are multiple choice, while others require a short answer or a solution to a puzzle. They can take as little as 15 minutes to complete or as long as four hours, depending on the test.

What do IQ tests measure?

“IQ tests are trying to measure an overall intellectual factor, which has been referred to as ‘g,'” says John DeLuca, PhD, a neuropsychologist and senior vice president for research at the Kessler Foundation. “A lot of things go into that factor, but ‘g’ is the idea of this overall intelligence.”

In an attempt to assess ‘g,’ each IQ test measures a slightly different set of cognitive skills. Some examples, Lexow says, include verbal reasoning, mathematical skills, visual-spatial reasoning, processing speed and working memory. Together, these attempt to assess both verbal and nonverbal aspects of intelligence, DeLuca says.

But contrary to popular belief, IQ tests do not determine how smart you are.

“An IQ test will tell you if you have some level of overall intellectual ability,” DeLuca says. “Does it mean you have common sense? No. It means you have an ability to process information at a high level. It doesn’t mean you’re smart in everything you do. Einstein [may have] had a high IQ, but it doesn’t mean he was able to, for example, make good decisions about his financial life.”

Lexow agrees. “Smartness and academic achievement are not the same as intelligence.” Terms like “smart” tend to be subjective, anyway, she says. For example, parents may label their children as smart because they can memorize or perform certain acts, but when measured objectively, their kids may be of only average intelligence—sorry, parents!

Conversely, someone with a reading disorder, such as dyslexia, may get poor marks in school but do well on nonverbal components of an IQ test, thereby demonstrating high intelligence.

What do IQ tests miss?

Since the first IQ test was administered more than a century ago, new theories of intelligence have evolved, and as a result, each IQ test takes a slightly different approach to measuring intelligence.

Many critics have charged that IQ tests fail to account for the many types of intelligence. Not only do they not assess decision-making skills, but they also overlook things like mechanical and kinesthetic intelligence, emotional intelligence and, in some regards, creativity. Emotional intelligence often refers to such skills as how to read people and how to read body language.

Lexow believes that IQ tests do measure creativity and flexibility to some degree because the tests require people to “think outside the box” for problem-solving. “However, the tests do not measure one’s social creativity,” or emotional intelligence, she says.

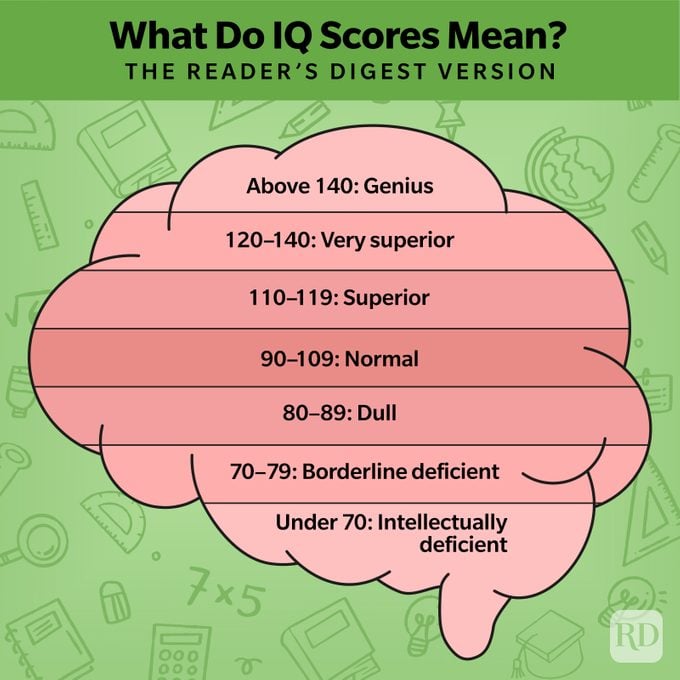

What IQ scores mean

IQ tests are scored on a bell curve, with a score of 100—the top of the bell shape on a graph—reflecting average intelligence. Using this metric, 50% of people will score 100, DeLuca says. Scores higher or lower than that fall on the sides of the bell and reflect standard deviations from average.

IQ scores also take age into account. That’s because it’s normal for certain aspects of intelligence to change over time. For example, your processing speed at age 20 is likely to be faster than at age 50, DeLuca explains, so the scores reflect what is average for your age group. So even if you take the same test 30 years apart, your IQ score should remain about the same.

Just as each IQ test measures slightly different aspects of intelligence, each also breaks down the range of scores slightly differently. With that in mind, this is how one of the most common IQ tests classifies scores:

Stanford-Binet

- Above 140: Genius or almost genius

- 120 to 140: Very superior intelligence

- 110 to 119: Superior intelligence

- 90 to 109: Average or normal intelligence

- 80 to 89: Dullness

- 70 to 79: Borderline deficiency in intelligence

- Under 70: Feeble-mindedness

FAQs about IQ tests

Does your IQ score determine your success in life?

No, not necessarily. Intelligence tests do not measure good everyday decision-making skills, and a person can be highly intelligent and still make poor or unhealthy decisions that inhibit success, Lexow notes. She adds that motivation is another big factor in success that has nothing to do with intelligence. Likewise, DeLuca notes that personality, which is independent of IQ, can have “a huge impact on how one functions and is successful in society.”

Do IQ tests measure intelligence equitably?

“IQ tests are designed and selected with cultural, racial, gender and socioeconomic status appropriateness in mind,” Lexow says. “Any factors that may interfere with an individual’s score are integrated into the interpretive results.”

Nevertheless, educational status and opportunities for intellectual enrichment can play a role, DeLuca says. “An intellectually stimulating environment will result in a higher level of overall ‘g.’ An impoverished environment will make it less likely that you have a higher ‘g,’ though it’s not a perfect relationship. There’s no absolute here.”

What other factors might affect IQ?

Nutrition, medical issues, mental health issues and even your mood or environmental distractions can affect performance on an IQ test, says Lexow.

As can drug use. Recent research, particularly among adolescents, has suggested that frequent cannabis use may negatively affect IQ, though studies suggest more research is needed. Adults are not immune to the cognitive effects of weed, as one study published in the American Journal of Psychiatry showed a decline of more than 5 IQ points, on average, from childhood to midlife among long-term cannabis users.

As for screen time, research is ongoing with regard to the effect of screen use on cognitive development. One study published in JAMA Pediatrics showed that screen time can negatively affect cognition and executive functioning skills, especially for children who were born extremely pre-term. Other studies suggest that the manner in which digital media is consumed may be more important than overall screen time.

Does a high IQ mean a lower risk of cognitive decline?

Thanks to the concept of cognitive reserve, DeLuca says, “people with a lifetime of highly intellectual stimulation will create a brain that’s more resistant to disease—not necessarily resistant to getting the disease or progressing in that disease, but resistant to the outcome of it,” he explains. “A person may be less likely to become demented even if they develop Alzheimer’s.”

Have IQ scores gone up or down over time?

“As a society, our fluid and crystallized intelligence scores have gone up over time. We call this the Flynn effect,” Lexow says. “Factors that impact the Flynn effect include educational changes, improvements in access to information, increased exposure to complex and difficult tasks and problems, and improvements in health and nutrition.”

About the experts

- Renee Lexow, PsyD, is a licensed clinical psychologist and supervisory psychologist for American Mensa. She holds a doctoral degree in clinical forensic psychology from the Chicago School of Professional Psychology. She is also the owner of Bella Living Psychological Services in Fort Worth, Texas.

- John DeLuca, PhD, is a neuropsychologist and senior vice president for research and training at the Kessler Foundation. He is also the director for the Center for Multiple Sclerosis Research at Kessler and interim director at Kessler’s Center for Stroke Rehabilitation Research. He has published more than 350 articles and book chapters on disorders of memory and information processing.

Sources:

- Biography: “What was Albert Einstein’s IQ?”

- Mensa: “What is IQ?”

- Harvard Graduate School of Education: “Multiple Intelligences”

- IQ Test Experts: “How do you interpret the IQ test scores?”

- American Journal of Psychiatry: “Long-Term Cannabis Use and Cognitive Reserves and Hippocampal Volume in Midlife”

- Psychological Medicine: “Intelligence quotient decline following frequent or dependent cannabis use in youth: a systematic review and meta-analysis of longitudinal studies”

- European Archives of Psychiatry and Clinical Neuroscience: “Age-related differences in the impact of cannabis use on the brain and cognition: a systematic review”

- JAMA Pediatrics: “Association of High Screen-Time Use with School-age Cognitive, Executive Function, and Behavior Outcomes in Extremely Preterm Children”

- Frontiers in Psychology: “Effects of screen exposure on young children’s cognitive development: A review”