I Think Black History Month Should Last All Year

Updated: Jan. 09, 2024

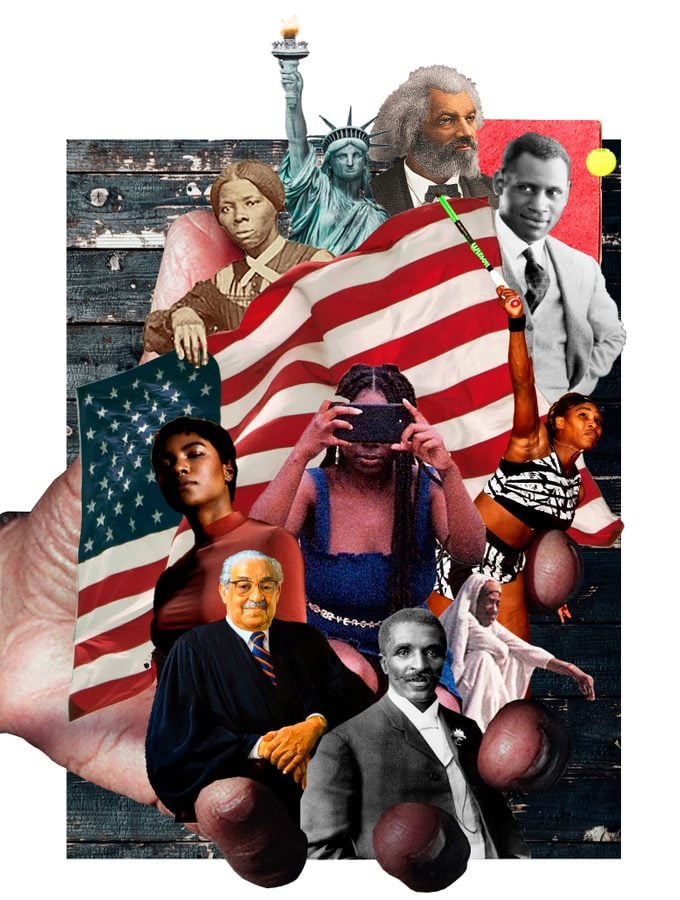

We know about Harriet Tubman and Martin Luther King Jr., of course. But our American history lessons skip over so many other African American achievers.

My feelings about Black History Month are complicated. On the one hand, I deeply appreciate the time to intentionally celebrate the brilliant contributions to American culture and history by people who look like me. But while absolutely worthy of celebration, the stories of African American contributions to our society have become repetitive over the years.

Harriet Tubman was so brave. Martin Luther King Jr. was the best orator of all time. George Washington Carver sure was a wiz with peanuts! Year after year, I hear a dutiful recitation of the same familiar facts, and I fear that the result is the mistaken impression that this is the sum total of African Americans’ role in our history.

Confining the history of an entire race of people to a 28-day period not only diminishes the significance of their contributions but also allows the greater truth to be erased. When I ask my African American friends about this, I often hear some version of “I’d rather have one month than no months.” But is that the only choice?

Black History Month traces its origins back to 1926, when the Association for the Study of African American Life and History designated a week in February, chosen to coincide with the birthdays of Abraham Lincoln (February 12) and Frederick Douglass (February 14), as what was then called Negro History Week.

The creation of that week was an important historical marker; its founder, Carter Woodson, an African American historian, intended for Black history to be taught as a part of American history and looked forward to the day when a designated period would no longer be needed. At that time, although it had been a half century since the abolition of slavery, Black people were still strenuously making the argument for their humanity.

There is nothing so motivating as knowing that people who look like you achieved great things. I know this from experience. My grandmother’s name before she married was Marian Robeson. She was the daughter of Benjamin Robeson, a minister and civil rights activist. Some will know his more famous brother, Paul Robeson, the scholar, activist, and entertainer remembered for his performance of “Ol’ Man River” in Show Boat. Their father, my great-great-grandfather William Drew Robeson, was a slave in North Carolina. He escaped to Philadelphia via the Underground Railroad. During the Civil War, he fought with the Union Army. And in 1876, this child of slavery graduated from Lincoln College with a degree in theology and then became a minister. My great-grandfather was one of his seven children.

Before she died, my grandmother shared with me her father’s sermons. In them, my great-grandfather, also a veteran, spoke eloquently about his love for a country that opposed his civil rights efforts.

I first read his moving writings when I was in law school, at a time when I began to let feelings of self-doubt creep into my consciousness. In this hypercompetitive world, I began to think that perhaps I wasn’t quite as smart as I thought I was, wasn’t quite as capable. Reading his words pushed me to think about how the full story of the accomplishments of Black people is so buried that we think of those we do celebrate as exceptional. Learned racism teaches us that there can’t possibly be so much Black excellence, that any accomplished Black person must be an outlier.

And then I discovered Ida B. Wells. Orphaned as a teenager, she went on to become a journalist, a mother, and an activist. She worked alongside Susan B. Anthony and Elizabeth Cady Stanton and pushed them to include Black women in the cause for suffrage. The story of the women’s suffrage movement is absolutely incomplete without understanding the efforts of Wells and her Black compatriots. Full stop. Here are 15 facts you probably didn’t know about Susan B. Anthony.

Reading her words made history so real for me, so painful but also so celebratory. Today, as a documentary filmmaker, I think of her fearless crusade for truth often, and I’m motivated to continue to tell important stories.

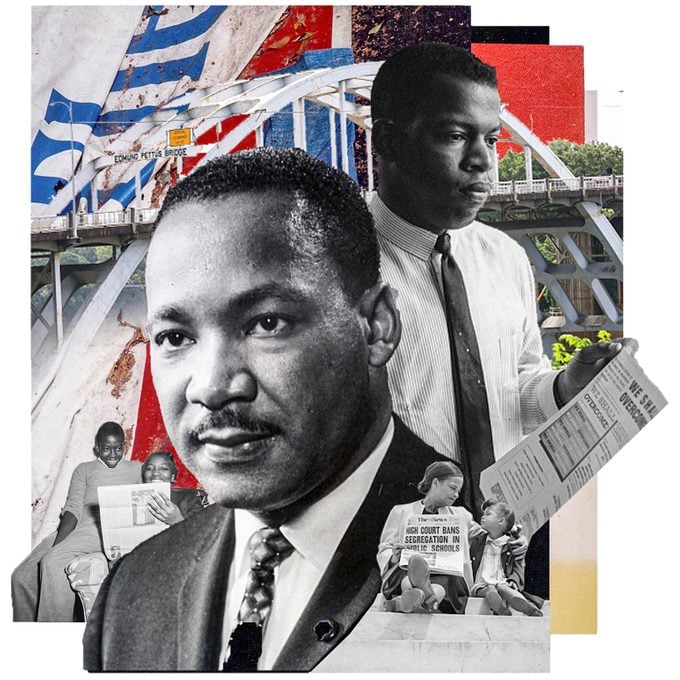

My most recent reminder of the power of story was my work directing a film about Rep. John Lewis called Good Trouble. I spent a year interviewing him and traveling the country with him. Watching hours of footage of a young Lewis strategizing and organizing, watching him deftly work with White and Black activists and politicians, I lived history through his eyes and experiences.

Walking through an airport with the congressman, I was constantly struck by the fact that he could not go more than a few feet without someone asking for a picture or to shake his hand. He always stopped and acknowledged and thanked the person. It was as if he sealed each interaction with an implicit understanding that every person he connected with would become an ambassador, that when they tell the story of John Lewis, it will assure that history lives on, even now, after his passing.

Because of my work and my interests and experiences, I am acutely aware of the need for accurate information in our media and our history books. Don’t we need this information all year long? Use these 12 ways to celebrate Black History Month all year long.

In 1976, the week that had been set aside to honor Black accomplishments was expanded to a month and called Black History Month. In the preceding 50 years, remarkable battles had been hard fought and won, including landmark Supreme Court cases that resulted in the 1954 decision in Brown v. Board of Education requiring the desegregation of public schools, the passage of the Voting Rights Act of 1965, and other civil rights laws guaranteeing basic rights of full citizenship to all people, regardless of race.

So now, some 40 years later, it’s time for Black history to enter the next phase. African Americans no longer need to argue that we deserve equal rights. With the establishment of the glorious National Museum of African American History and Culture on the National Mall in Washington, DC, we no longer need to make the case that our contributions are worthy of noting and celebrating.

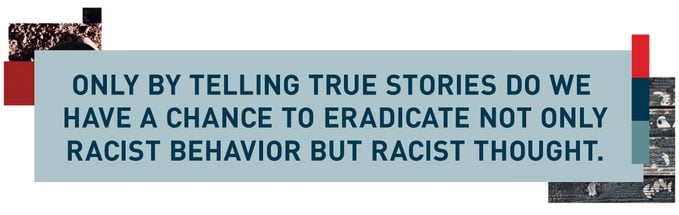

But racism and discrimination on the basis of race continue to be a stain on our country. And only by telling true stories do we have a chance to eradicate not only racist behavior but also racist thought. We have to face head-on the untrue idea that only White people contribute substantially to our country’s cultural, scientific, legal, and other advances.

To dismantle this false narrative, the first place we should look is the story we tell about ourselves. I am confident that given the opportunity, a host of scholars would gladly take a pen to outdated history books—break them apart and add the rich context that includes the contributions of not only African Americans but native and Asian people, women, and every other marginalized group. History is not a pie; my having more does not leave you less.

I’m a “plus … and” person. I think we need Black History Month. I also think we should challenge our educators and ourselves to consistently search out and share stories and facts that expand our understanding of history to include all who play a role in it. Acknowledging that America is a multicultural society and that the accomplishments and contributions of people who are not White are real, substantial, and important is proof that the American ideals so many of us profess to value are real.

I asked my friend, the noted historian and scholar Henry Louis Gates Jr., for his thoughts on this, to which he quickly replied, “Every day should be Black History Month!”

Yes, sir. Every day.

Next, read one woman’s perspective on why Black History Month is more important than ever.

Dawn Porter is a documentary filmmaker. Her film John Lewis: Good Trouble is out now.