Black history facts for Black History Month

Each February, the United States observes Black History Month, a monthlong celebration that honors the contributions made by Black Americans. During this time, people support Black-owned businesses, share powerful Black History Month quotes and research Black History Month facts to educate themselves on groundbreaking people, places and events.

We may understand what Black History Month is about, but how much do we really know about this annual event and those it honors? From the historian who established it to the different themes each year, here are some Black History Month facts, along with little-known Black history facts your schools might have left out.

Get Reader’s Digest’s Read Up newsletter for more history and holidays, fun facts, humor, cleaning, travel and tech all week long.

A historian helped establish Black History Month

Here’s a Black American you may not have learned about in school: Historian Carter G. Woodson, the creator of what we presently know as Black History Month, worked passionately to establish the event in an effort to provide an education on the origins, struggles and achievements of African Americans in United States history. Originally, it existed as seven days of commemoration, first established in 1926 and called “Negro History Week.” Woodson penned more than a dozen books, including 1933’s, The Mis-Education of the Negro.

Black History Month has been nationally recognized since 1976

Despite its forerunner, Negro History Week, originating all the way back in 1926, Black History Month as we know it today didn’t become nationally recognized until the 1970s. Black students and educators at Kent State first celebrated Black History Month in January and February of 1970. Other educational institutions started following suit, and for the United States Bicentennial, President Gerald Ford recognized Black History Month, as has every president since.

Black History Month has a different theme each year

Since its official inception in 1976, Black History Month has grown to become an event celebrated by cultural institutions such as theaters, libraries and museums, as well as by corporations like Google and Target. But did you know it has a different theme each year?

Every year, the Association for the Study of African American Life and History (ASALH) chooses a theme around which to center their Black History Month celebrations. The theme for 2024 is “African Americans and the Arts,” acknowledging creatives, from Black poets and writers to visual artists and dancers, for their fight against oppression through their craft.

Black History Month is observed during different months around the world

This may be one of those Black History Month facts that’s new to you. The United States, Canada and Germany observe Black History Month in February. However, in the United Kingdom, Ireland and the Netherlands, they honor it during the month of October.

The founding of the NAACP coincides with Black History Month

On Feb. 12, 2024, the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) will celebrate its 115th birthday. The date of Feb. 12, 1909, was chosen for the NAACP’s inception because it also marked the 100th birthday of Abraham Lincoln and coincided with abolitionist Fredrick Douglass’s birthday, on Feb. 14. As one of the most interesting Black history facts, the NAACP is America’s oldest civil rights organization, as well as its largest.

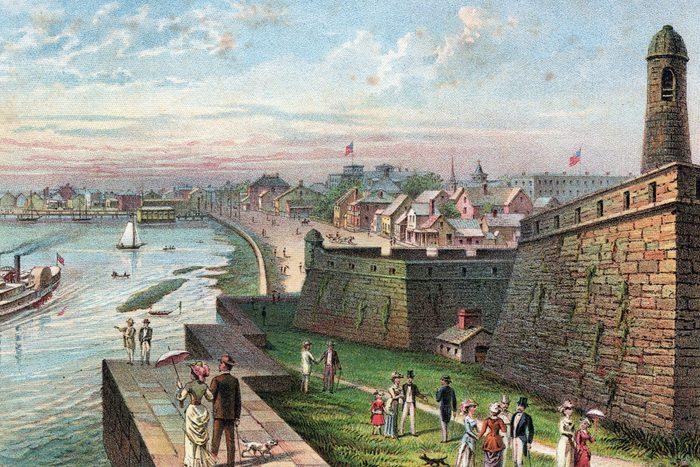

Fort Mose is an important town in Black history

Of all the cities you learned about in school that no longer exist, Fort Mose (pronounced “Mo-say”) is one of the most important. Here’s one of the little-known Black history facts: More than 250 years ago, when people who had escaped their enslavement made their way to St. Augustine, Florida, they were welcomed by the Spanish, who valued their skills and contributions. In 1738, the governor rewarded them by establishing the town that went on to become known as Fort Mose.

It was the first officially sanctioned town for freed Black men in what is now the United States, with a population of about 100. In 1763, the Fort was ceded to the British under the Treaty of Paris, and the free Black residents were evacuated to Cuba with the Spanish. The British then destroyed the site during the War of 1812. Today, it is a Historic State Park, making it one of the wonderful American landmarks that celebrates Black culture.

The first state to abolish slavery was in New England

Considering President Abraham Lincoln hailed from Illinois and was the president who would eventually abolish slavery, you might expect that the first state to do away with the practice was his Midwestern state of origin. However, it was Vermont that led the way, in 1777.

The practice of vaccination in America has interesting roots

An enslaved person by the name of Onesimus, brought to the Massachusetts colony, told church minister Cotton Mather about the way inoculations were practiced in Africa for centuries to prevent people from getting sick. Mather took this information to Dr. Zabdiel Boylston when smallpox became a severe issue in Boston in 1721, reports History.com. Boylston inoculated more than 240 people, despite a large opposition to the practice.

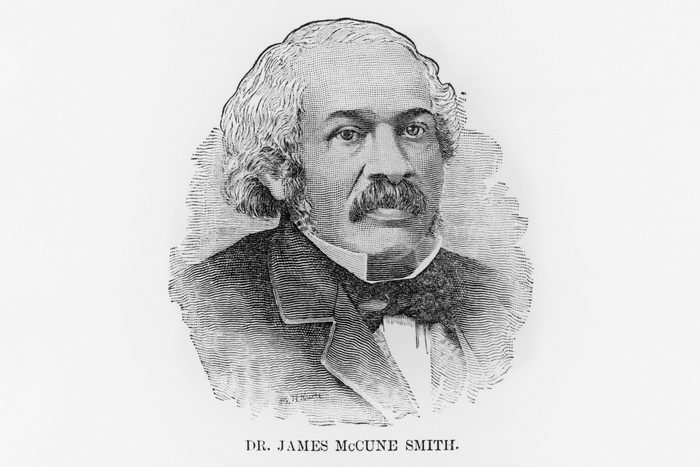

James McCune Smith was the first African American doctor

James McCune Smith was the first African American to hold a medical degree and the first African American to run a pharmacy. Because no American university was willing to admit him, he was forced to travel to Scotland to earn his degree from the University of Glasgow.

After graduating in 1837, he practiced medicine for nearly two decades at the Colored Orphan Asylum in Manhattan, contributed papers to scholarly journals and was widely respected as an intellectual. He was an abolitionist who helped enslaved people escape and find their way to freedom via the Underground Railroad. Despite his accomplishments, Smith was never admitted into the American Medical Association.

The first public high school for African Americans opened in 1870

The first public high school for African Americans, Paul Laurence Dunbar High, opened in Washington, DC, in 1870, just five years after the end of the Civil War. Named after Dunbar, the acclaimed Black writer, the school graduated many luminaries, including the first Black Army General, the first Black presidential cabinet member and the first Black graduate of the Naval Academy. Many high schools, including Dunbar Vocational High School in Chicago (pictured above), have also adopted Dunbar’s name.

Black men had a strong presence in the Wild West

You’d be hard-pressed to find much diversity in old-time Western films; however, according to Smithsonian Magazine, one in four cowboys was Black. In fact, it’s believed that the fictional character of the Lone Ranger was based on Bass Reeves. Reeves was born into slavery, but he fled westward during the Civil War. In time, he became a Deputy U.S. Marshal.

George Edwin Taylor ran for president in 1904

Long before Barack Obama became the first Black president of the United States, George Edwin Taylor ran for president in 1904 as a member of the National Negro Liberty Party. Though the journalist and newspaper editor received only 2,000 votes, Taylor deserves to be remembered for his groundbreaking political run.

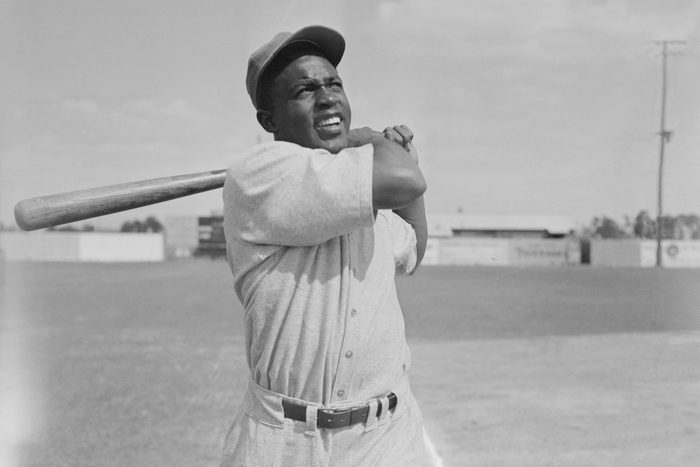

Jackie Robinson broke baseball barriers

On April 15, 1947, Jackie Robinson played in his first game as one of the Brooklyn Dodgers. During his first season in the major leagues, he led the National League with the most stolen bases and then was honored as Rookie of the Year. Despite his talent and skill, Robinson faced adversity from fans and colleagues; he later became an outspoken member of the Civil Rights Movement for Black equality.

Charlotta Bass paved the way for Kamala Harris

A major glass ceiling and racial milestone was broken in November 2020 when Kamala Harris, the daughter of Jamaican and Indian immigrants, was elected as America’s first Black vice president (as well as the first woman and South Asian American to hold the office!). She was not the first Black woman to run for that office, however. In 1948, a journalist named Charlotta Bass became the vice presidential nominee of the Progressive Party, with Vincent Hallinan as her running mate. She was also from Harris’s home state of California!

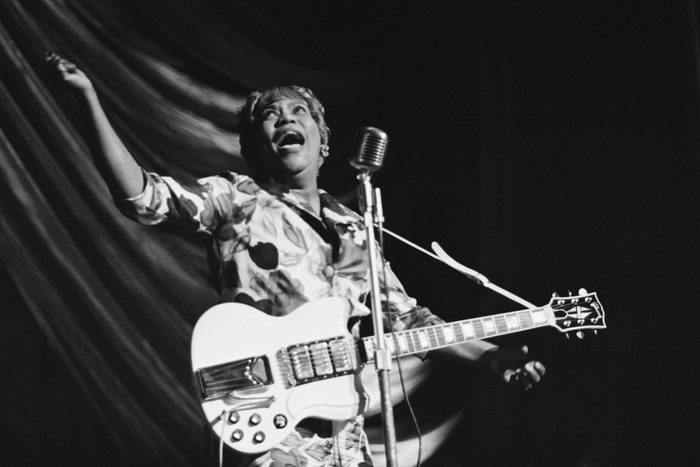

Sister Rosetta Tharpe knew how to rock

When it comes to rock ‘n’ roll, the boys seem to get all the credit—but Sister Rosetta Tharpe was known as the “Godmother of Rock ‘n’ Roll” for a reason. Born in 1915, Tharpe blazed a musical trail with her distinctive voice and rollicking guitar, combining both secular and spiritual music in her own unique brand of rock. Greats like Chuck Berry, Elvis Presley, Bob Dylan and Johnny Cash have credited her influence on their music.

Betty Boop was inspired by a Black jazz singer

She may have been drawn as an old Hollywood pinup girl, but cartoon Betty Boop was actually based on Esther Jones, a Harlem-based jazz singer. Jones was known for her use of “boops” in her singing as well as what was called a child-like scat, similar to that of her illustrated counterpart.

Quincy Jones, the Grammy-nominated music man, made history

Quincy Jones hits the history books as the most nominated artist in Grammy history. He has scored a total of 80 nominations and 28 awards. Not surprisingly, he was presented with the Grammy Legend Award back in 1992. Jones is also one of the founders of the Institute for Black American Music.

Claudette Colvin pre-dated Rosa Parks in refusing to give up her seat on public transportation

Many people learn about Rosa Parks fighting for desegregation on a Montgomery, Alabama, bus, but they may not know this Black history fact: Claudette Colvin, a young girl, did it before Parks. In 1955, at just 15 years old, she stayed seated and refused to move to the back of the bus for a white passenger. She was subsequently arrested. According to NPR, Colvin had learned about the plight of Harriet Tubman and other early activists in school before her arrest.

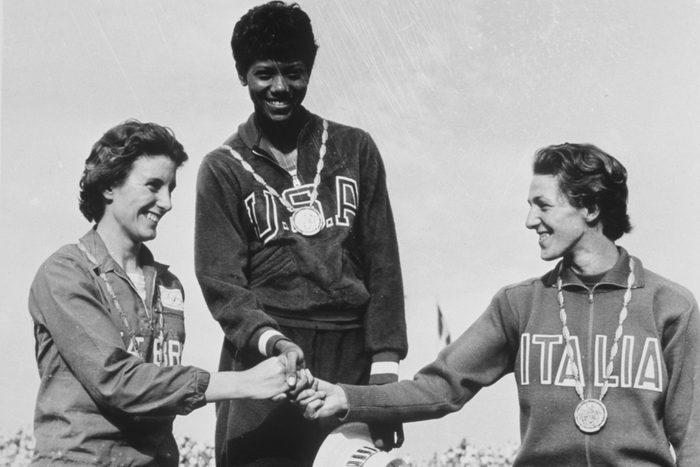

Wilma Rudolph was a pioneering Olympian and activist

Wilma Rudolph was an African American athlete who became the first woman to win three medals at the Summer Olympics in 1960. Having achieved her dream, she returned home and refused to participate in a celebratory parade if it was segregated. As a result, the parade and banquet thrown in her honor were the first events to be integrated in her hometown of Clarksville, Tennessee.

Interracial marriage was banned in the U.S. until 1967

Way back in 1664, marriage between races was banned in the United States. This law was first enacted in the Colony of Maryland, with others quickly following suit. It might seem surprising today that this took more than 300 years to overturn—but it’s less unbelievable when you understand the full depth of institutional racism and what it means.

The National Civil Rights Museum is in a somber location

Everyone should visit the National Civil Rights Museum in Memphis, Tennessee, an immersive experience, steeped in history and emotion. And it’s not only the artifacts the museum houses that are notable. The museum itself is located on the former site of the Lorraine Motel, where Martin Luther King Jr. was tragically assassinated.

The facade is still there to remind visitors of what happened that day. Noelle Trent, PhD, Director of Interpretations, Collections and Education at the museum, tells Reader’s Digest, “The preservation of historic sites, especially the Lorraine Motel, is important because the physical structures, space and geography interpret history in a manner that cannot be expressed by words or photographs. There is power in a place.”

Martin Luther King Jr.’s assassination coincided with an icon’s birthday

It was on Maya Angelou‘s 40th birthday, April 4, 1968, that her friend, civil rights activist Martin Luther King Jr., was assassinated. After this heinous act, Angelou stopped celebrating her birthday. However, she sent flowers to King’s wife, Coretta Scott King, on that date until Mrs. King passed in 2006.

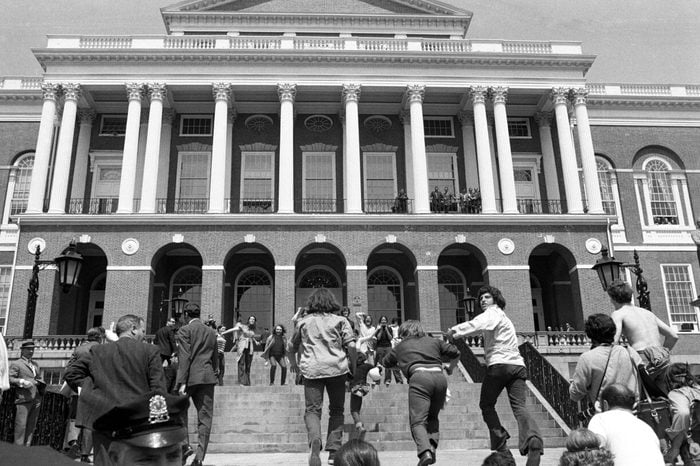

Students had a big impact on the Civil Rights Movement

When we think of the heroes of the Civil Rights Movement, we usually think of towering figures like Rosa Parks and Martin Luther King Jr., but the movement also comprised ordinary young people who wanted to change the world by fighting injustice.

“Young people have been critical actors in the fight for civil rights in the United States,” shares Trent. “From the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee and the Congress for Racial Equality’s Freedom Riders to 1964 Freedom Summer’s Council of Federated Organizations, youths were participants and leaders in key protest movements. They leveraged their innovative techniques to work within the community to challenge the status quo.”

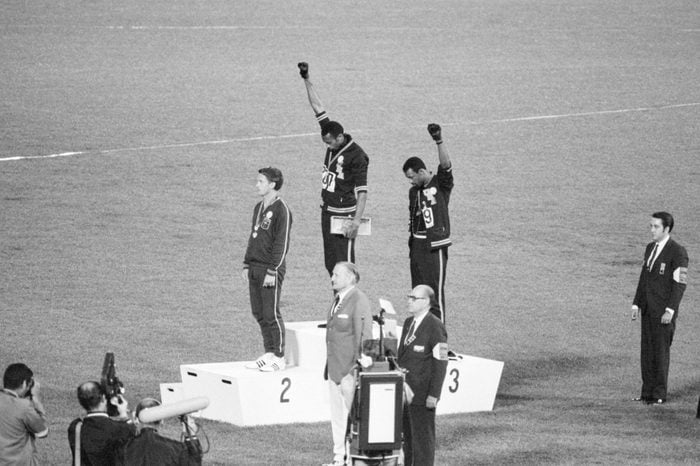

Civil rights solidarity in sports has deep roots

Many years before Colin Kaepernick took a knee during the national anthem, two other athletes sent a powerful message about their unity with Black America. During the 1968 Olympic games in Mexico City, competitors Tommie Smith and John Carlos wore black gloves and gave a Black power salute during the anthem.

The first African American woman was elected to the House of Representatives in 1968

Paving the way for women of color in Congress (and the White House) was Shirley Chisolm, who represented New York in the House of Representatives. Just four years after she entered the House, in 1972, she became the first Black candidate for a major party’s nomination in the race for president of the United States.

Additional reporting by Tamara Gane.

About the expert

- Noelle Trent, PhD, is the Director of Interpretations, Collections and Education at the National Civil Rights Museum in Memphis.

Sources:

- History.com: “Black History Facts”

- BBC News: “Black History Month: What is it and why does it matter?”

- National Museum of African American History & Culture: “Celebrate Black History Month 2024”

- Smithsonian Magazine: “The Lesser-Known History of African-American Cowboys”

- History.com: “How an Enslaved African Man in Boston Helped Save Generations from Smallpox”

- Florida Museum: “Fort Mose”

- NPR: “Forebears: Sister Rosetta Tharpe, the Godmother of Rock ‘n’ Roll”

- The Conversation: “Before Kamala Harris, many Black women aimed for the White House”

- NPR: “A Forgotten Presidential Candidate from 1904”