8 Red Flags Voter Suppression Is Happening in Your Area—And How to Make Sure You Can Cast a Vote

Updated: Nov. 24, 2022

Voter suppression is almost as old as America itself. Here's how to resist it in 2020.

Controversies over mail-in voting, threats about sending sheriffs to polling places, and slowdowns in mail delivery have stoked concerns about voter suppression in this year’s general election. But voter suppression—the attempt to prevent citizens from exercising their right to vote—is nearly as old as America itself.

The history of voter suppression

As far back as 1787, voting was restricted to wealthy White male landowners, leaving decisions about commoners’ rights to the states. In Maryland, Jewish people were not allowed to vote in until 1828. Black Americans weren’t guaranteed the right to vote until the 15th Amendment was passed in 1870—a full five years after the Civil War ended. Even then, Southern states tried to limit Black participation in elections through intimidation, poll taxes, literacy tests, and Jim Crow laws. And women weren’t allowed to vote nationwide until the 19th Amendment passed in 1920. (Want to learn more? Check out these 15 essential books for understanding race relations in America.)

In 1964, the 24th Amendment banned poll taxes, and the following year, the Voting Rights Act passed, prohibiting other voter suppression methods.

That hasn’t stopped certain political factions from trying. Today’s tactics may look different, but they are just as powerful. Read on to learn what voter suppression may look like in your community, and what you can do to make sure your vote counts when you head to the polls the first Tuesday in November.

What counts as voter suppression?

In general, there are two broad types of voter suppression: actions that prevent people from casting a ballot, and those that prevent someone’s vote from being counted.

But Myrna Pérez, director of the Voting Rights and Elections Program at the Brennan Center for Justice, a nonpartisan law and policy institute, says it’s important to be aware that some challenges that suppress voting are the result of a lack of resources and improper planning rather than any malevolent intent. “In the best of circumstances, we underfund our elections,” she says. “They are not built to withstand the stress and challenge that a once-in-a-hundred-years pandemic put on our system.”

That said, the following red flags may indicate attempts at voter suppression in your community.

Voter registration obstacles

Some states make it difficult for people to register to vote. For example, states may require people to register far in advance of the actual election, disqualifying those who have recently moved. Some states insist that a voter’s name must exactly match how it is recorded in other official databases, with no exceptions for accent marks, hyphens, double surnames, or other irregularities, Pérez says. Some states even impose fines for holding voter registration drives and submitting incomplete forms, so you’ll want to find out if there are restrictions in your state on holding voter registration drives. Find out the bizarre things the government actually has the power to do.

Purging voter rolls

States routinely purge inactive voters—those who have moved, died, or not recently voted—from their rolls, Pérez says, with no nefarious intent. However, she says states must comply with a federal law that prohibits purging for the 90 days before a federal election. “You will see a lot of purging happening outside those blackout periods,” she adds. Even so, state election boards are not allowed to remove you until they’ve gone through a process that requires waiting for four years, she says.

Sometimes, voters are removed erroneously. For example, in 2017 Georgia removed a half million people from its rolls, and 87,000 of them were still eligible voters. Voters of color were disproportionately affected.

Pérez recommends that voters check to make sure they’re still registered one month before Election Day, and then again one week before and one day before.

Intimidation

Pérez calls this the “most obvious” type of voter suppression, one in which individuals are “intimidating, deceiving, or getting in the way of voters casting a ballot.”

Intimidation can be subtle, such as when a government official falsely suggests that voting by mail is not safe, Pérez says. Or it can be more overt, such as when President Donald Trump suggested in an interview with Fox News host Sean Hannity on August 20 that he would send sheriffs and other assorted law officials to the polls—an action expressly prohibited by law. Even if police aren’t present, a random individual could show up brandishing a gun at a polling place, making voters feel threatened, Pérez says.

If you are attempting to vote in person and someone intimidates you, Pérez suggests calling law enforcement. If that doesn’t feel safe, she advises telling a poll worker, calling the media, or even the Department of Justice. She stresses, however, that just because you see a law officer on-site, it doesn’t mean they’re there to intimidate you. Police may have been called to deal with any number of conflicts, including people who are being disruptive about mask-wearing requirements. “We’ll all have to be very discerning and strive to make things go as smoothly as possible…while also protecting our rights,” she says.

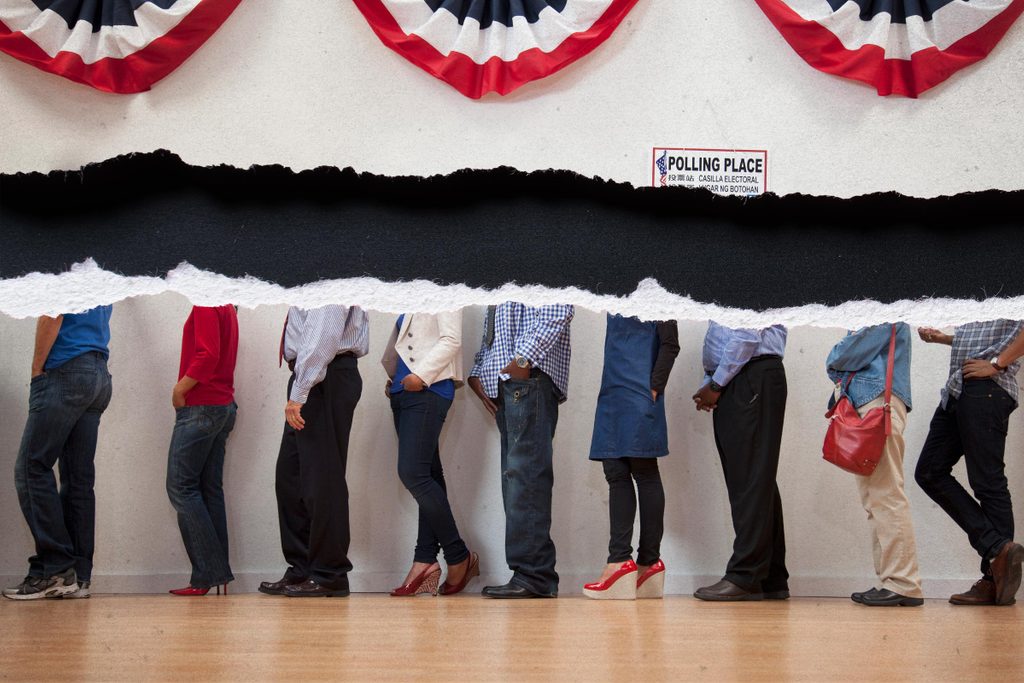

Reduction in polling places

In the past decade, efforts to close polling places and make it more difficult for some voters to cast a ballot have multiplied. In their report, “Democracy Diverted,” the Leadership Conference Education Fund found 1,688 polling place closures between 2012 and 2018 in the counties with the most pervasive patterns of discrimination. Texas, Arizona, and Georgia—all states with rapidly diversifying electorates—were among the worst offenders.

More recently, in this year’s primary election, voters in Milwaukee, Wisconsin, had only five polling places anywhere in the city where they could cast a vote—down from 182 in 2016. In Kentucky, primary voters’ polling locations were slashed from 3,700 to 170 statewide, with only one voting location available in almost every county.

Ideally, election materials mailed to voters will announce any closures. Still, citizens should check online at Vote.org for any changes before they vote. And they should consider early in-person voting before Election Day if their state permits it.

“Expect some glitches on Election Day. Many more people are going to vote than ever before in a presidential election,” Pérez predicts. She suggests voters adopt strategies like going to the polls first thing in the morning, practicing patience if they open late, discussing the possibility with employers that they might be late, and having backup child/elder care, or vote via mail-in ballot (more on that below). “Voters need to do as much as possible to persevere,” she says.

Interfering with mail-in ballots

Because of the ongoing coronavirus pandemic, many people are nervous about voting in person and are ready to embrace mail-in ballots, Pérez says. But in mid-August, the U.S. Postal Service was reported to be removing mail-collection boxes and mail-sorting machines in several states and reducing hours at post office locations around the country. The moves have raised concerns that voters won’t be able to request, complete, and return absentee ballots in time for them to be counted.

As a result, many states are encouraging voters to use ballot drop-off boxes that are not associated with the USPS. Trump called their safety into question in a tweet on August 17, but the risk of tampering is infinitesimally small. Typically, the boxes are secured, locked, and under video surveillance and located outside of public locations such as town halls, libraries, and even near Starbucks and McDonalds in Oregon. Election workers who process the ballots must follow a strong chain of custody.

Pérez says that mail and drop-off box locations should be publicized on printed and digital election materials, but in a year with so many moving variables, they may not be. Voters can always call their local election officers for the most updated information. And if they find out politicians are trying to limit their access to ballot boxes, Pérez says, “they should immediately contact their legislators and tell them they don’t support this. Folks are looking at this as potential litigation.”

Most importantly, Pérez advises that people should request their ballots as early as possible, fill them out right away and return them immediately. It’s also important to follow instructions to a T: use the right color ink, sign your ballot or envelope where indicated, and make only one clear selection for each office or issue.

Stricter ID requirements

Thirty-six states require or request some form of voter identification. Of those, seven have strict laws that require voters to present a government-issued photo ID before they can cast a ballot. More than 21 million Americans don’t have this type of ID, however, due to fees, lack of transportation to acquire the ID, disabilities, and other factors, according to the American Civil Liberties Union. What’s more, the types of ID that are permissible seem to favor certain demographics. For instance, Texans can use a handgun license but not a student ID card from a state university. According to the Brennan Center, “more than 80 percent of handgun licenses issued to Texans in 2018 went to White Texans, while more than half of the students in the University of Texas system are racial or ethnic minorities.”

Voter ID laws are in place purportedly to prevent voter impersonation or other types of fraud. However, numerous studies have shown that such fraud is extraordinarily rare—occurring somewhere between 0.00000003 percent and 0.0025 percent of the time, depending on the report.

Voters can pressure their legislators to eliminate such restrictive laws, but for this election, the best defense is to be prepared. Look up your state’s voter ID laws and make sure you have everything you need before you head out to the polls on Election Day. You’ll be inspired by these 13 rarely seen photos of the first women voters in 1920.

Gerrymandering

Gerrymandering refers to redrawing the lines of voting districts in such a way that the voting results in that district are predetermined in favor of one political party. Voters can contact their legislators and election boards to insist that independent commissions and not politicians draw up their district lines. Find out 15 interesting facts and figures about the Constitution.

Felony disenfranchisement

In every state but two (Maine and Vermont), people with felony convictions are restricted in some manner or at some time from voting. Pérez says some states only disenfranchise felons while they’re in prison; others require felons to finish probation or parole, while still others disenfranchise felons who’ve committed certain types of crimes for life. Pérez is optimistic that this type of voter suppression will recede further. “We’ve had an incredible move forward. For the first time in the country’s history, there is no state that permanently disenfranchises all people with felony convictions.”

Next, learn the answers to the 15 political questions you’re too embarrassed to ask.

Sources:

- DoSomething.org: “7 Signs Voter Suppression Could Be Happening Near You”

- Brennan Center for Justice: “Voter Registration Drive”

- Leadership Conference Education Fund: “Democracy Diverted”

- Vote.org: “Polling Place Locator”

- The New York Times: “Will You Have Enough Time to Vote by Mail in Your State?”

- AP News: “Ballot drop boxes seen as a way to bypass the post office”

- ACLU: Block the Vote: Voter Suppression in 2020

- Vote.org: “Voter ID Laws”

- Brennan Center for Justice: Debunking the Voter Fraud Myth

- The New York Times: “What is Gerrymandering?”