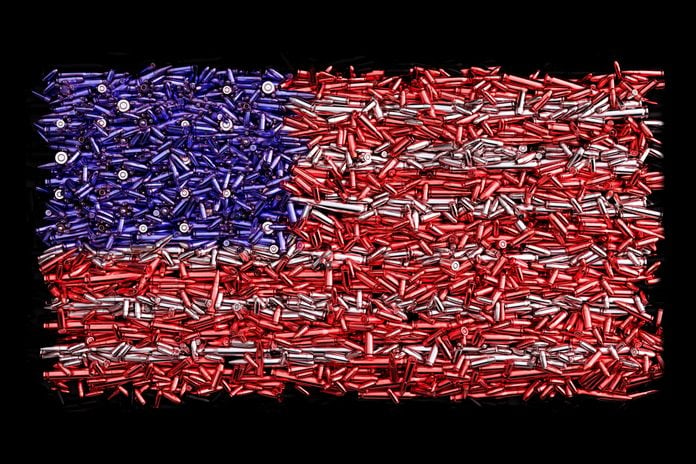

Why Is It So Hard to Stop Gun Violence in America?

Updated: Mar. 27, 2023

It's clear that gun violence in America is a serious problem. So what's keeping our country from addressing it effectively?

As a longtime civil rights activist and member of We Are Women Warriors, a Buffalo, New York–based community empowerment group, Katherine “Kat” Massey was dedicated to ending gun violence in America. And she put in the work. Taking an education-centered approach, she spoke directly to members of her community and wrote opinion pieces for Buffalo newspapers to bring awareness to the impact of gun violence in predominantly Black neighborhoods.

At the age of 72, Massey was showing no signs of slowing down, determined to make her community a safer place for the next generation. But her life came to an abrupt end on Saturday, May 14, 2022, when she was one of 10 people shot and killed in a Buffalo supermarket.

Tragically, the attack in Buffalo—the deadliest incident of gun violence in America in 2022 to date—was only one of the shootings that took place over the course of that weekend. There were also two other incidents the following day that made national headlines: One person was killed and five were injured when a man opened fire on a Taiwanese congregation in Laguna Woods, California, while two people were shot and killed at a flea market in Harris County, Texas.

According to a May 2022 report from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC)—which identifies gun violence in America as a public health issue—the first year of the COVID-19 pandemic saw the highest rate of firearm homicide since 1994, with a total of 19,515 deaths. That figure increased to 20,915 in 2021. As of May 17, 2022, there had been 7,161 gun-related homicides in the United States, including 203 mass shootings (defined as a shooting in which four or more people have been shot or killed in a single incident), according to the Gun Violence Archive.

This is far more than a question of Americans’ right to bear arms. The impact of gun violence extends beyond those who were killed, and it includes the lasting impacts on mass shooting survivors, as well as the mental health implications of growing up in a country where active shooter drills are as commonplace as fire drills in schools. And if gun violence statistics like the ones we’ve seen over the past few years haven’t been enough to prompt meaningful cultural and legislative change, what will it take?

Is the gun violence problem really unique to America?

As of 2021, the United States had the 32nd-highest rate of deaths from gun violence in the world, according to the latest information culled by NPR using data from the University of Washington’s Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation (IHME), which, according to its website, “tracks lives lost in every country, in every year, by every possible cause of death.” In 2019, the latest full year for which information has been made available, the United States saw 3.96 gun-related deaths per 100,000 people. That’s 100 times more gun-related deaths than in the United Kingdom, where access to guns by members of the general public is strictly regulated.

It can’t be mere coincidence that the United Kingdom, boasting some of the strictest gun regulation in the world (they have banned civilian ownership of handguns since 1997, following an elementary school shooting), has far fewer gun deaths per person—especially when you consider that crime rates in general for the United States are roughly the same as the crime rates for all democratic nations and almost precisely at the average for all nations in the world.

No matter how you might feel about the right to bear arms versus the need for gun control in the United States, it’s clear from these facts and from these gun violence statistics in the United States that too many Americans are losing their lives to gun violence. So, the question really is: What is stopping the United States from regulating the possession and use of firearms in a manner that would halt the rise of gun violence in America while still permitting Americans to bear arms?

First things first: The issue goes beyond the Second Amendment

With a single sentence, the Second Amendment to the U.S. Constitution ignited a debate about gun ownership in America that, more than 200 years later, has yet to be resolved. It reads: “A well regulated Militia being necessary to the security of a free State, the right of the people to keep and bear Arms, shall not be infringed.” Archaic language aside, if that line leaves you with more questions than answers, you’re not alone.

Like the rest of the Constitution, the Second Amendment is, by design, left open to interpretation—especially when you factor in what’s known as the Constitution’s “elastic” or “necessary and proper” clause. Found in Article I, Section 8, this clause looked to the future of the new and evolving country, giving Congress the power to enact laws that reflect changing times, unforeseen circumstances, and new challenges. While that stipulation became a foundational part of American democracy, it has become a particular problem when it comes to gun control laws, because those on both sides of the issue can (and do) claim that their interpretation of the Second Amendment is backed by the Constitution.

So, in addition to the Second Amendment’s lack of clear guidance on the right to own firearms, the elastic clause adds to the confusion, spurring further debate.

The federal government has not passed gun control legislation in more than 25 years

Over the last several decades, gun control has become so overwhelmingly partisan that Congress has simply not been able to agree on legislation. In fact, no significant federal gun control laws have been enacted since 1994, when President Bill Clinton signed the Violent Crime Control and Law Enforcement Act, popularly known as the “Assault Weapons Ban.”

However, the ban expired in 2004, and since then, all attempts to renew it have failed. The most notable attempt was the Assault Weapons Ban of 2013 in the wake of the Sandy Hook Elementary School shooting in Newtown, Connecticut, where 20 children and six educators were murdered by a lone gunman. Even with bipartisan support, the bill was defeated in the Senate, with 41 Republican senators joined by four Democrats voting against it. (It required at least 60 votes to pass.) Since that time, all Democrat-led efforts to pass tougher gun control laws have failed.

“Political dynamics have done a great disservice to attempts to come up with effective legislation to curb gun violence in America,” says Joseph Blocher, a constitutional scholar and Duke University School of Law professor.

By contrast, some states have passed their own gun control legislation

“Another important story is what’s happening—and what’s possible—at the local level,” Blocher tells Reader’s Digest. “The costs and benefits of guns look very different in urban and rural areas, and historically guns have been regulated much more heavily in cities. Even the infamous cow towns of Dodge City and Tombstone [of the late 1800s Wild West] prohibited gun-carrying in city limits. And still today, openly carrying a rifle in the woods during deer season means something very different than doing the same thing in Manhattan during rush hour.”

Although there has been a lot of legislative activity with regard to guns at the state level in recent years, especially after the school shootings in Newtown and Parkland, Florida, some have been to increase gun safety measures, while others have reduced restrictions. States including Connecticut, New York, and California have tightened their gun laws; Arizona, Tennessee, Arkansas, Kansas, Idaho, and the Dakotas have further deregulated guns. In case you’re wondering, here’s what it would take to amend the Constitution.

Americans agree on gun regulation more than you might think

Putting aside the smaller picture of state and local governments, as well as a deeply partisan Congress, the fact is that Americans, overall, may not disagree nearly as much as political rhetoric would have you believe. “If you ask people whether it’s more important to prioritize gun rights or gun regulation, the gap between parties would appear to be enormous, and higher than for just about any political issue,” Blocher explains.

However, when the question is phrased a different way, one that presumes the right to bear arms does, will, and must exist in the United States, you get a completely different response. “Many people who don’t identify as gun control advocates nonetheless favor expanded background checks in advance of gun purchasing,” says Blocher. In fact, a majority of Americans support stronger gun control laws, including background checks, according to a recent USA Today/Ipsos poll.

The “intensity gap” may play a role in thwarting new gun legislation

The polarization of American politics is another reason policy has stalled on the national level. On the one hand, there is the “long tradition of gun ownership in America, combined with an ideology of mistrust of government, and a belief in individualism,” says Robert Spitzer, PhD, a political science professor at the State University of New York at Cortland and author of The Politics of Gun Control. And there is the National Rifle Association (NRA), which, according to Spitzer, “promotes an extremist, apocalyptic vision of government and society that has had the effect of hardening much of the gun community to any idea of participating in the construction of sensible gun laws that could address many of the nation’s gun problems.”

On the other hand, you have what Spitzer calls “consistent majorities supporting stronger gun laws.” But while there certainly are motivated and vocal supporters of gun control—including the vast number of parents who have lost children to gun violence who passionately advocate for stronger gun laws—casual gun control advocates tend to be far less mobilized than the average gun owner. And, as Spitzer points out, a highly motivated minority can often win the day over a large but fairly apathetic majority. There’s even a name for the phenomenon: the “intensity gap.”

There are signs, however, that this may start to change, Blocher suggests. We may already be seeing some of the seeds of this, especially in the past 10 years, with the growth of gun violence prevention groups such as the Brady Campaign, Moms Demand Action, and Everytown for Gun Safety.

Additionally, as psychologists and sociologists continue to study the motivations of mass shooters and the warning signs of a potential attack, law enforcement officials should, at least in theory, have a better grasp on how to prevent school shootings and other incidents of gun violence in America. And sometimes, new information comes from seemingly unlikely sources, like an ex-gunman who has shed light on what it will take to stop the next mass shooter.

The paradox of gun control and crime control

As much as increased gun control may be needed to curb gun violence in America, the paradox appears to be that loosening restrictions for civilians to carry guns has been helpful at reducing crime, according to Spitzer. However, appearances can be deceiving. While gun-toting civilians patrolling their neighborhoods may be able to discourage break-ins, they have no impact whatsoever on crimes involving gun violence—except to the extent that they, themselves, are causing those numbers to increase. And indeed, they have. As gun restrictions have loosened for civilians, gun violence has increased, including suicides. Moreover, “states with more permissive gun laws and greater gun ownership had higher rates of mass shootings,” according to a 2019 study published in The BMJ.

So where does that leave Americans? Apparently, as a nation, if we are making headway in the war against crime in general, we are still doing so at the expense of a significant and disturbing number of human lives.

More Stories About Gun Violence in America

|

What can the United States learn from other nations?

In the wake of the May 2022 mass shooting in Buffalo, New York, President Joe Biden issued a statement calling the deadly attack “a racially motivated hate crime,” adding that “we must do everything in our power to end hate-fueled domestic terrorism.” Part of the “we” the president was referring to was Congress. A month prior, following an April 2022 mass shooting in Sacramento, California, Biden implored lawmakers to impose background checks on gun buyers and to ban assault weapons, high-capacity magazines, and ghost guns.

Some in support of those measures point to steps other democratic nations have taken in response to gun violence. For example, after a 2019 mass shooting that left 51 religious worshipers dead in New Zealand, where gun regulation had long been somewhat relaxed and whose gun lobby was known to be particularly powerful, lawmakers swiftly enacted gun legislation. It included the creation of a firearms registry that requires gun-license holders to update their status whenever they buy or sell firearms.

Although it will take some time to see whether New Zealand’s strict firearms regulations will result in a long-term change in the country’s gun culture, in 2020—the year following the mass shooting in Christchurch—the number of gun-related crimes did increase. While opponents of New Zealand’s tougher gun laws say the legislation isn’t working, proponents note that the increase in those figures is the product of improved police data collection.

Meanwhile, there is reason to be hopeful, because it appears that imposing more rigorous gun control is something nations with low gun violence death rates all have in common. In fact, a 2018 analysis conducted by journalism students at the University of Wisconsin on non-war gun deaths in democratic countries revealed that when compared with Japan, the United Kingdom, Canada, and India, the United States, which has the least restrictive gun control laws by far, had the highest rate of violent gun deaths. Having said that, enacting stricter laws is only one part of the equation. There would also have to be a major shift in culture to curb gun violence in America.

Where does that leave us?

The fact remains that the United States likely won’t ever embrace gun control laws that are as restrictive as, say, the United Kingdom’s. However, we may benefit from looking to Italy as an example. Italy has a significant gun culture, but mass shootings are not a problem there. The reasons for that are complicated, but one fact is quite simple: Anyone over the age of 18 can legally own a gun in Italy as long as they apply for a license, take a firearms safety course, and stay on the right side of the law (i.e., those with criminal records cannot obtain a weapon, or if they already own a gun, it must be surrendered). Further, they must obtain a certificate from their doctor to the effect that they do not suffer from addiction or mental health issues. And all of this is true no matter how a gun is acquired, whether by purchase, gift, or bequest.

According to both Spitzer and Blocher, there is something to be said for this approach. “Expanded background checks are a sensible place to start,” Blocher says. “That’s a proposal that’s overwhelmingly popular, plainly constitutional, and eminently sensible. It’s a way to keep guns from getting into the wrong hands in the first place.” And as Spitzer points out, what President Biden is asking for could, indeed, help mitigate the problem of gun violence in America. While nothing on the table can be seen as a panacea, “better analysis and monitoring of gun sales and qualifications for ownership have demonstrable value.”

While Congress continues to debate the issue of universal background checks, on April 11, 2022, the White House announced that the Department of Justice has issued a final rule to rein in the proliferation of “ghost guns” (i.e., guns that are not manufactured commercially, but rather are put together at home and harder to trace). That policy also included two additional executive actions to reduce gun violence in America. The first is ensuring that firearms with split receivers are subject to more stringent regulations requiring serial numbers and background checks when purchased from a licensed dealer, manufacturer, or importer. The second requires federally licensed firearms dealers to retain certain records until they shut down their business, and then hand them over to the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms and Explosives—taking away their option to legally destroy most records after 20 years. It is expected that President Biden’s executive actions will face legal challenges from advocates of gun rights.

Additional reporting by Elizabeth Yuko.

Sources:

- Buffalo News: “Katherine ‘Kat’ Massey: ‘We lost a powerful voice'”

- CDC: “Vital Signs: Changes in Firearm Homicide and Suicide Rates — United States, 2019–2020”

- Gun Violence Archive

- NPR: “Gun Violence Deaths: How the U.S. Compares with the Rest of the World”

- IHME: “On gun violence, the United States is an outlier”

- Constitution Annotated: “ArtI.S8.C18.1 The Necessary and Proper Clause: Overview”

- World Population Review: “Crime Rate by Country 2022”

- Joseph Blocher, Duke University School of Law professor and constitutional scholar

- Robert Spitzer, PhD, political science professor at the State University of New York at Cortland and author of The Politics of Gun Control

- Ipsos: “Americans favor stricter gun laws, though support has declined from 2019”

- The BMJ: “State gun laws, gun ownership, and mass shootings in the US: cross sectional time series”

- The Observatory: “Non-war gun deaths higher in U.S. than in many democracies”